Top Stories

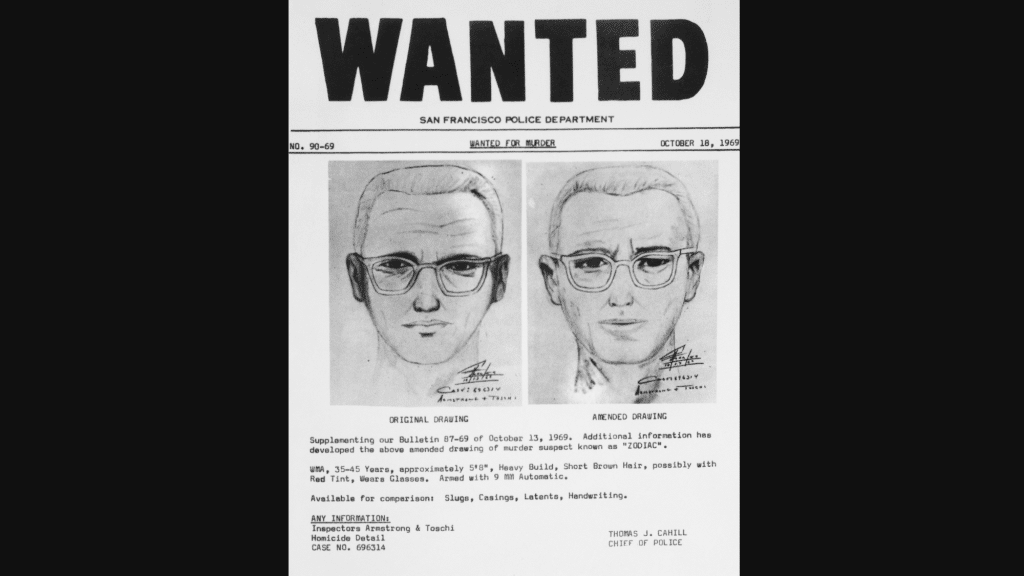

The Zodiac Killer case remains one of America’s unsolved mysteries, having captured the attention of true crime enthusiasts and investigators for over five decades. If you are searching for the most recent news, updates, and developments related to the Zodiac

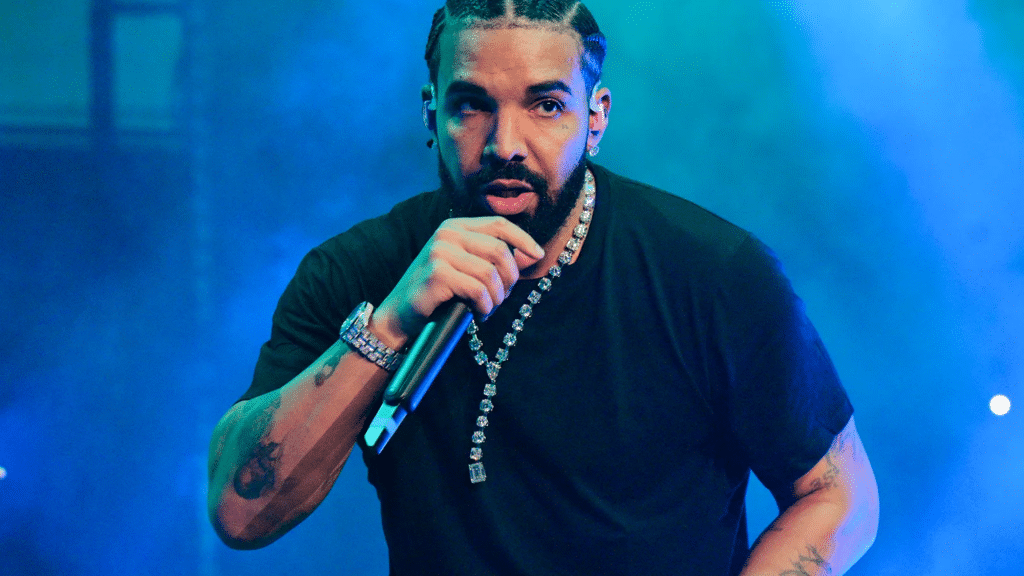

Are you curious about how many albums Drake has released so far? We have got you covered! From his start on Degrassi to becoming one of the biggest names in music, Drake has dropped hit after hit. But with studio

LATEST

Top Stories

By the Certified Technicians at EasyFix Appliance LTD | Technical Safety BC Certified | 20+ Years Industry Experience Most appliance breakdowns are preventable. After two decades of repairing refrigerators, washers, dryers, and kitchen appliances across thousands of homes, we have

LATEST

Top Stories

Relationship depression is that heavy, low-energy season when being “together” still feels lonely. You might dread conversations, feel numb during affection, or assume the worst about the future. Some couples fight more, others go quiet, but both can feel stuck.

Welcome to cuindependent, your space for bold ideas, fresh perspectives, and engaging stories. We bring you content that informs, inspires, and sparks conversation.

Stay connected — subscribe to our newsletter and never miss an update!

Explore

Our Picks

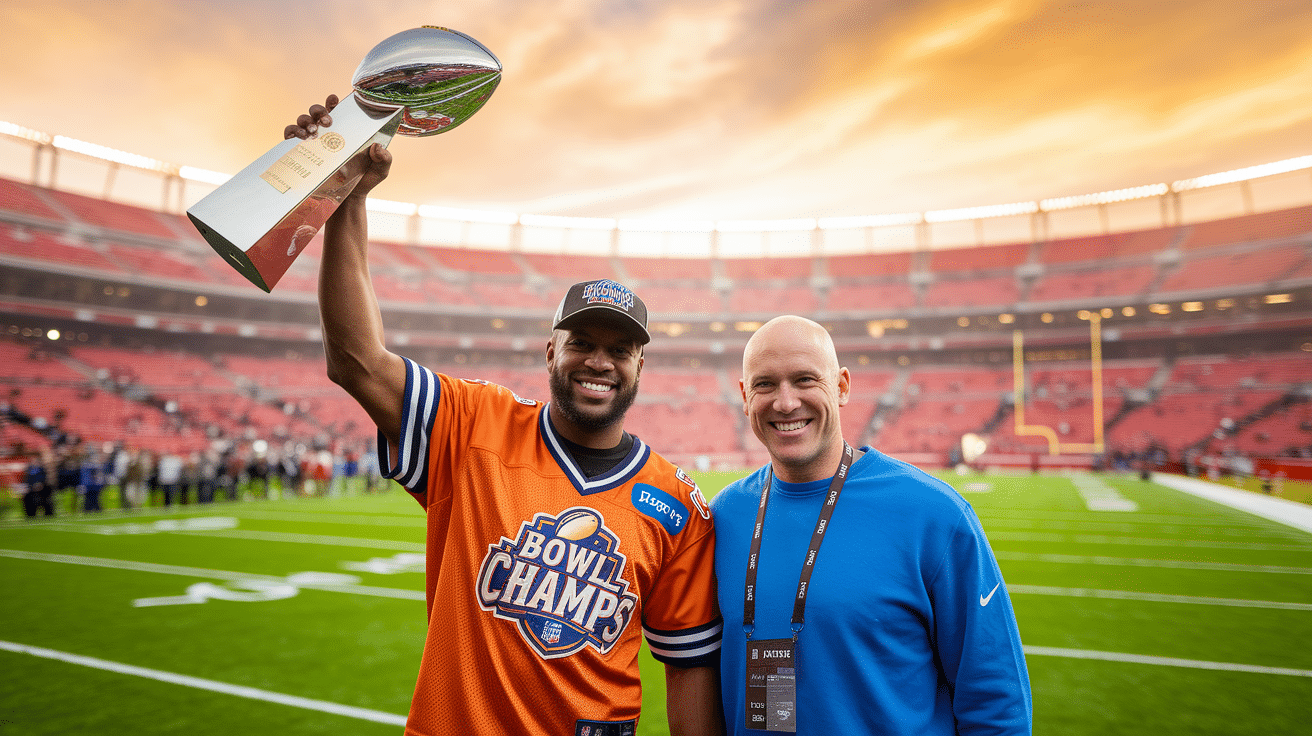

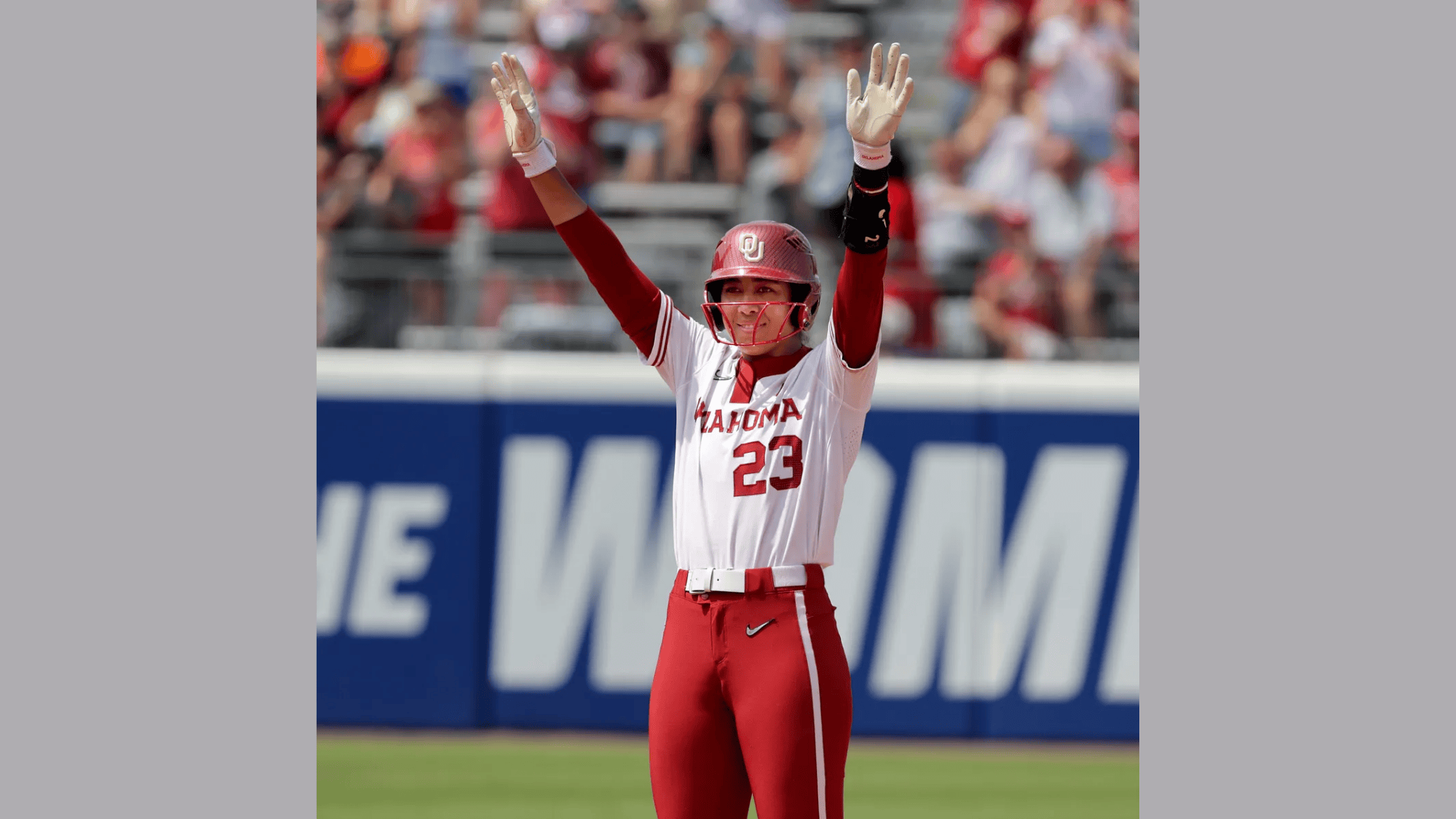

From inspiring artistry to achievements in sports and beyond, we bring the highlights.

A curated view of stories shaping conversations across fields today.

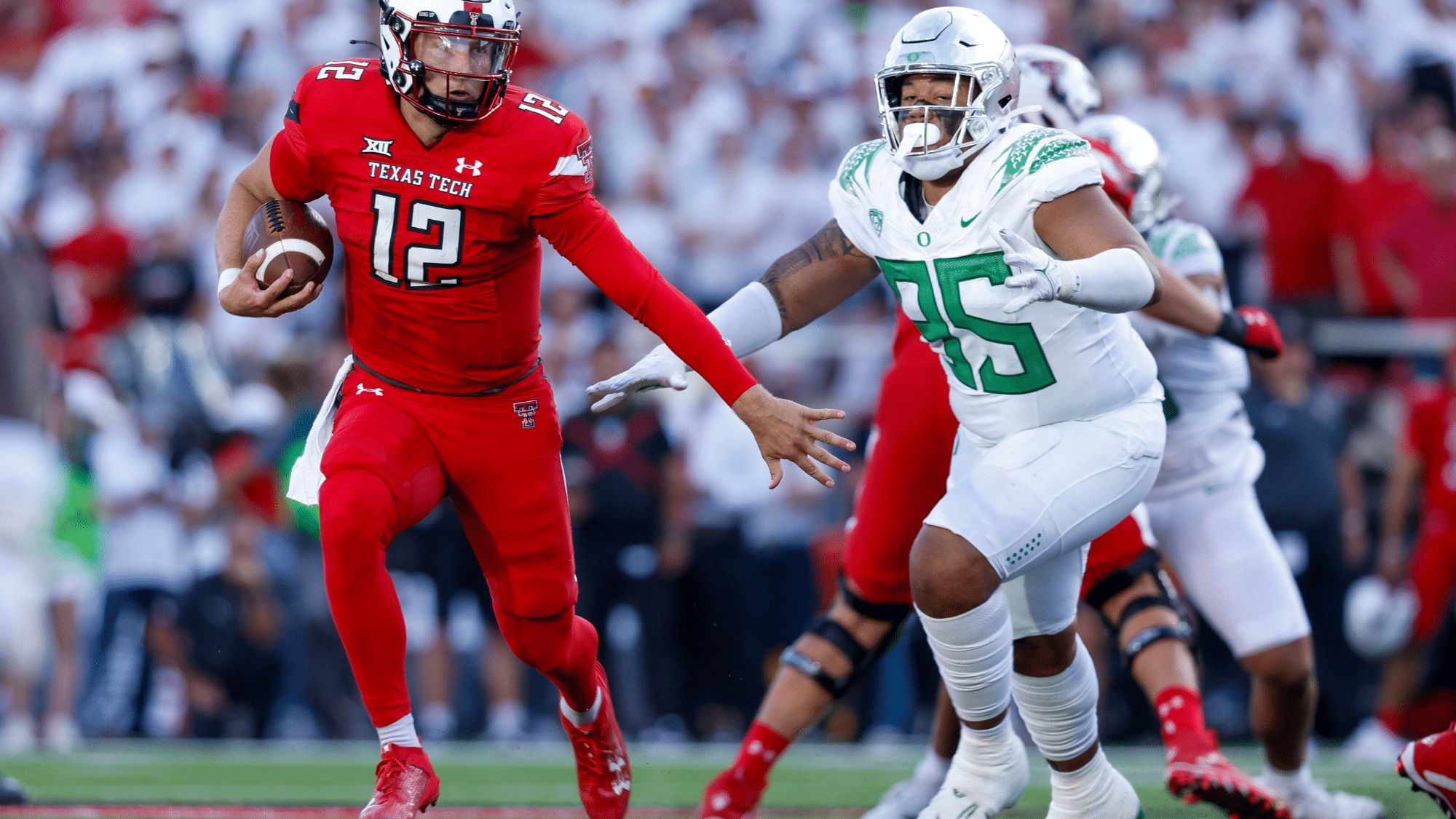

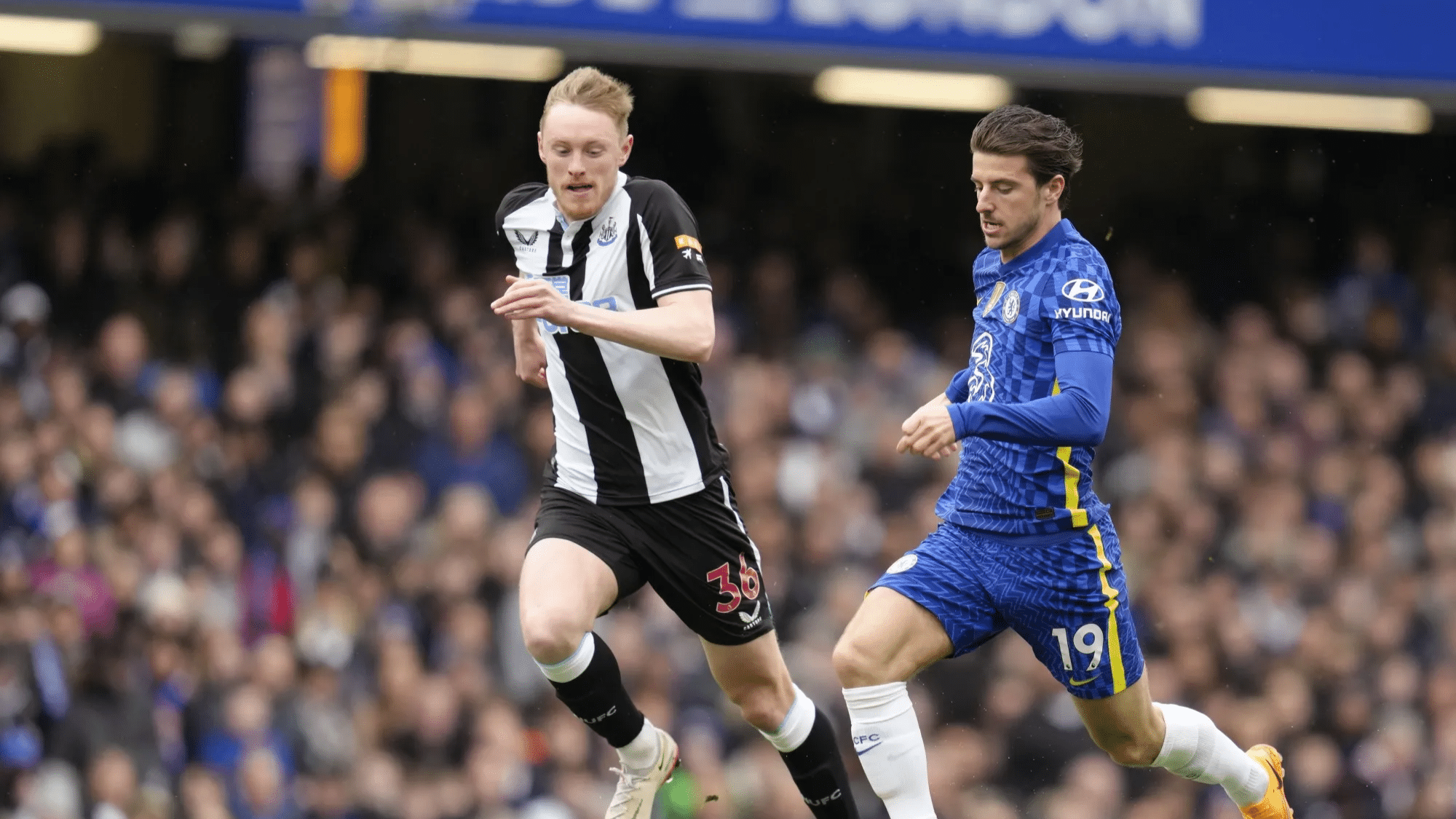

Some games aren’t just played, they are felt in the soul. These iconic rivalries go beyond the scoreboard, turning into battles of pride, passion, and identity that echo across generations. Whether it’s football in Argentina or cricket in India, these matchups light up stadiums, stir entire nations, and write unforgettable chapters.....

Fall is a magical season filled with vibrant colors, changing leaves, and endless creative inspiration. For teachers and parents, it’s the perfect time to introduce fall art projects that help children explore textures, colors, and nature while developing fine motor and creative skills. If you’re planning a classroom craft or.....

more

Meet Our Team

At CU Independent, we’re committed to delivering real, bold, and honest stories. Get to know the passionate team behind the content!

Samantha Lee

(Editor-in-Chief)

Dr. Alex Thompson

(Senior Features Writer)

Meet Our Team

Hootie & the Blowfish is a beloved American rock band, best known for their chart-topping hits in the 1990s. Formed in 1986 in Charleston, South Carolina, the band quickly rose to fame with their unique blend of pop, rock, and blues. Their catchy songs and relatable lyrics connected with fans, making.....

Canada’s online gambling sector operates under a patchwork of provincial rules, and the differences between jurisdictions affect what games you can access, how quickly you get paid, and how much protection you have as a player. Ontario launched its regulated market on April 4, 2022, becoming the first province to require.....

Why Web Apps Break as Businesses Grow Let’s be honest. Most web applications don’t fail because of technology choices. They fail because the business outgrows the assumptions baked into them. Off-the-shelf platforms help teams move fast early on. But over time, processes change, integrations multiply, and edge cases start to.....

Private label clothing brands require manufacturing partners delivering quality, reliability, customization flexibility at scale. Finding experienced custom clothing manufacturers China determines whether brands launch successfully or struggle with production delays, quality inconsistencies, communication breakdowns. China manufacturing ecosystem offers unmatched production capacity, material sourcing, technical expertise – but navigating thousands of factories.....

Our Contributors

As Seen On