CU Independent | Celebrity, News, Art & Lifestyle Insights

Top Stories

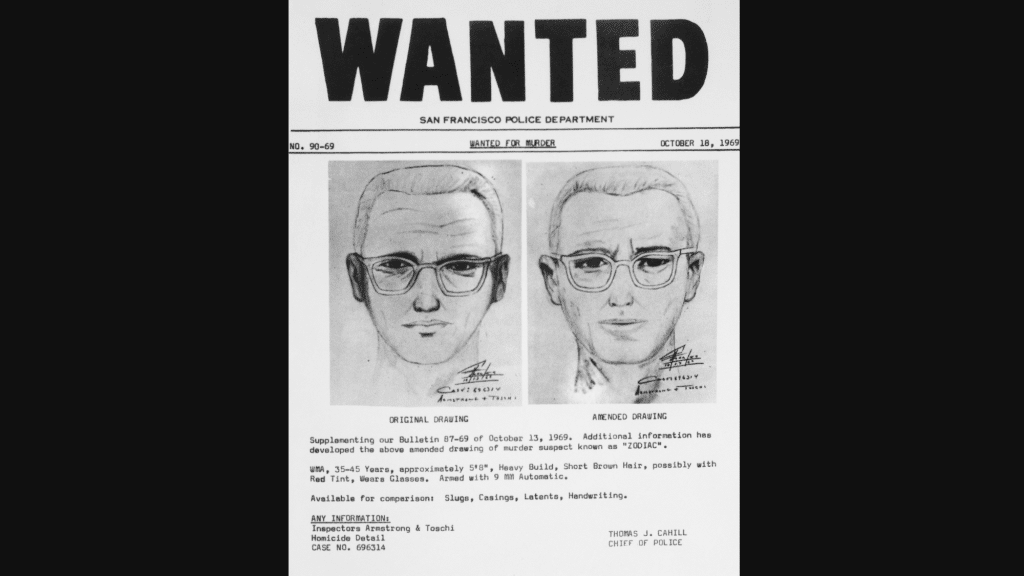

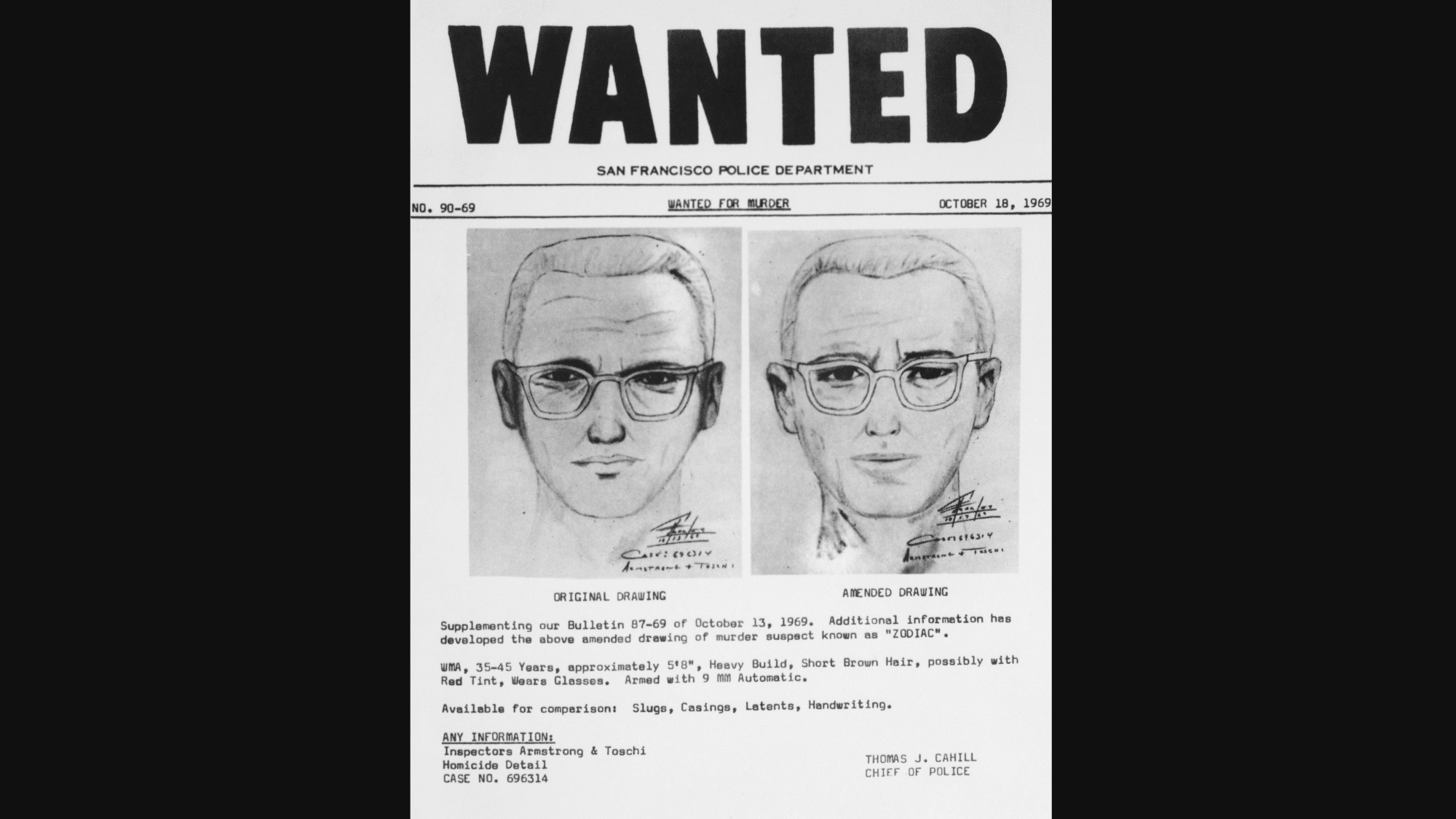

The Zodiac Killer case remains one of America’s unsolved mysteries, having captured the attention of true crime enthusiasts and investigators for over five decades. If you are searching for the most recent news, updates, and developments related to the Zodiac

Latest

Top Stories

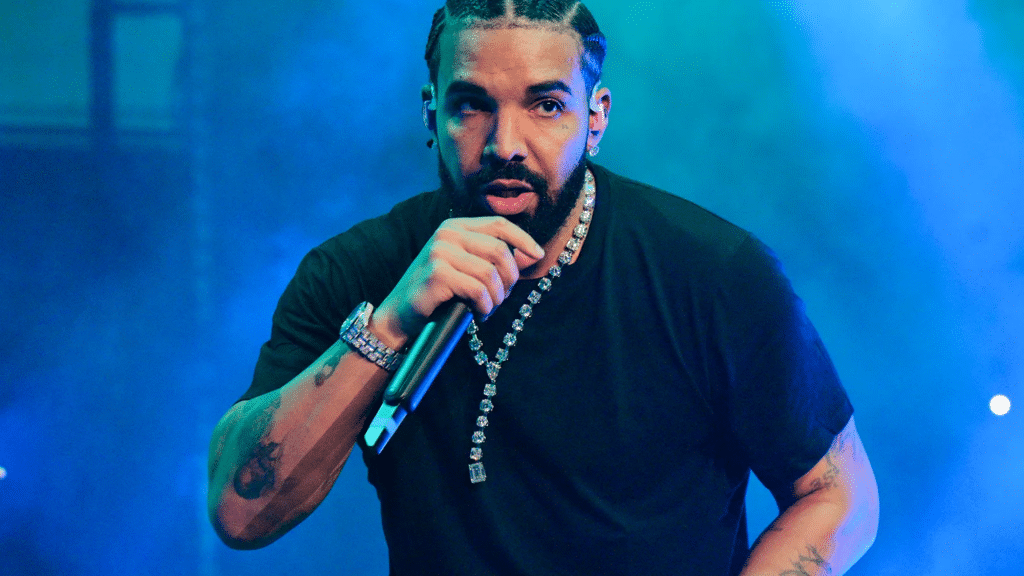

Are you curious about how many albums Drake has released so far? We have got you covered! From his start on Degrassi to becoming one of the biggest names in music, Drake has dropped hit after hit. But with studio

latest

Top Stories

Waking up with puffiness under one eye can be surprising and concerning. One-sided swelling often points to a specific cause, while the other eye looks normal. Common triggers include allergies, sinus pressure, minor irritation, or fluid retention. Understanding the cause

Celebrity

Sexuality

Welcome to cuindependent, your space for bold ideas, fresh perspectives, and engaging stories. We bring you content that informs, inspires, and sparks conversation.

Stay connected — subscribe to our newsletter and never miss an update!

Explore

Our Picks

From inspiring artistry to achievements in sports and beyond, we bring the highlights.

A curated view of stories shaping conversations across fields today.

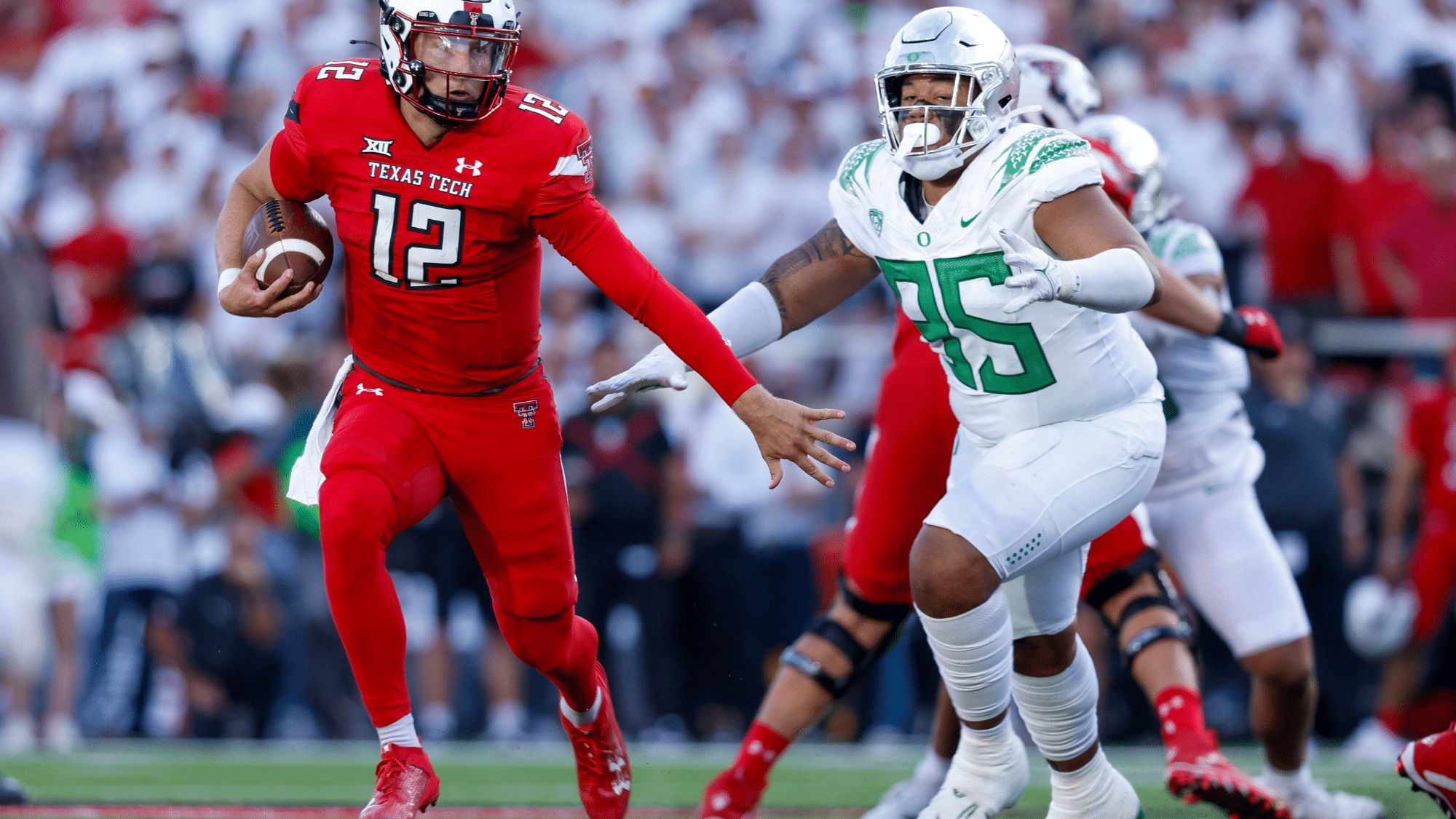

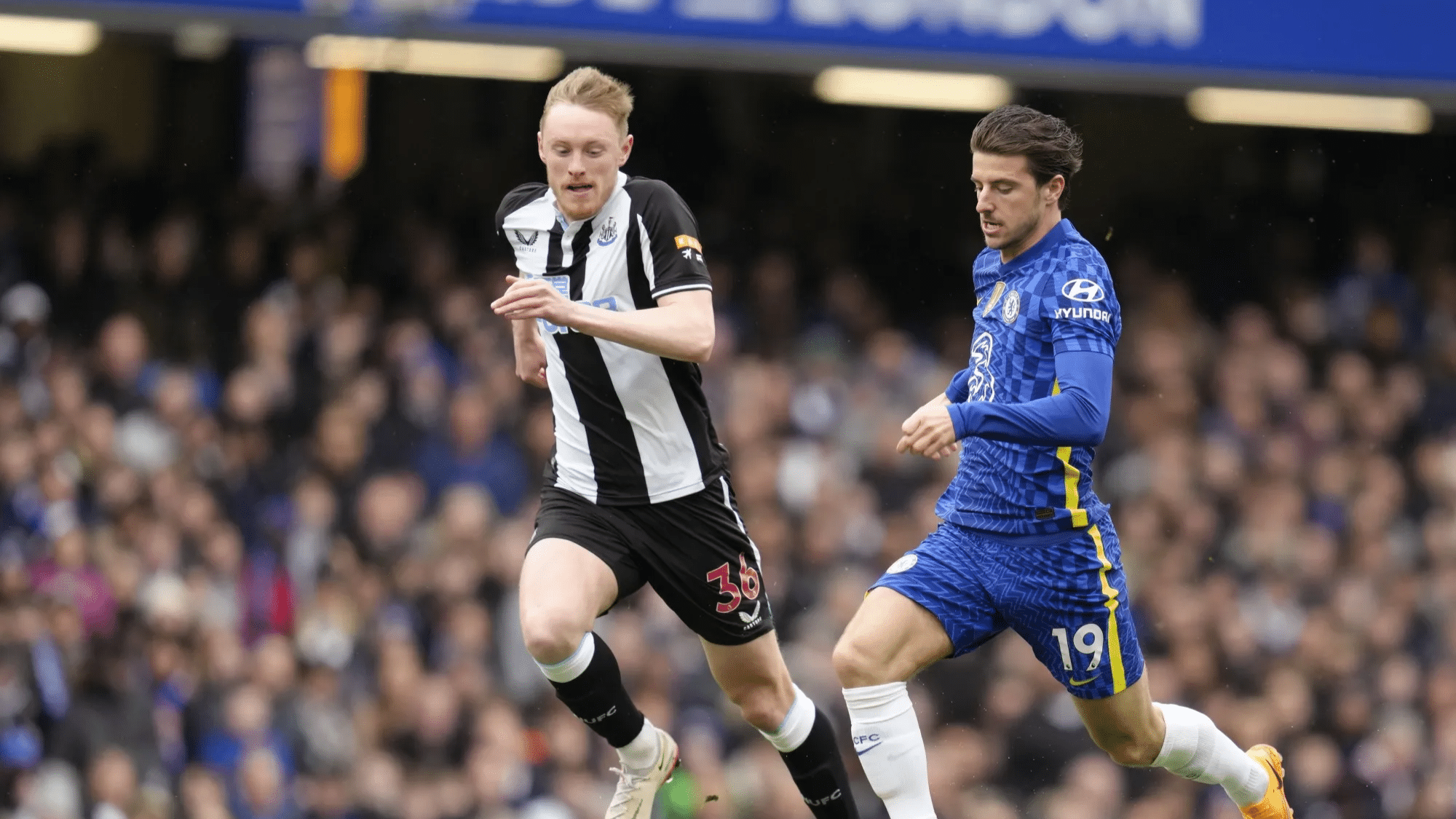

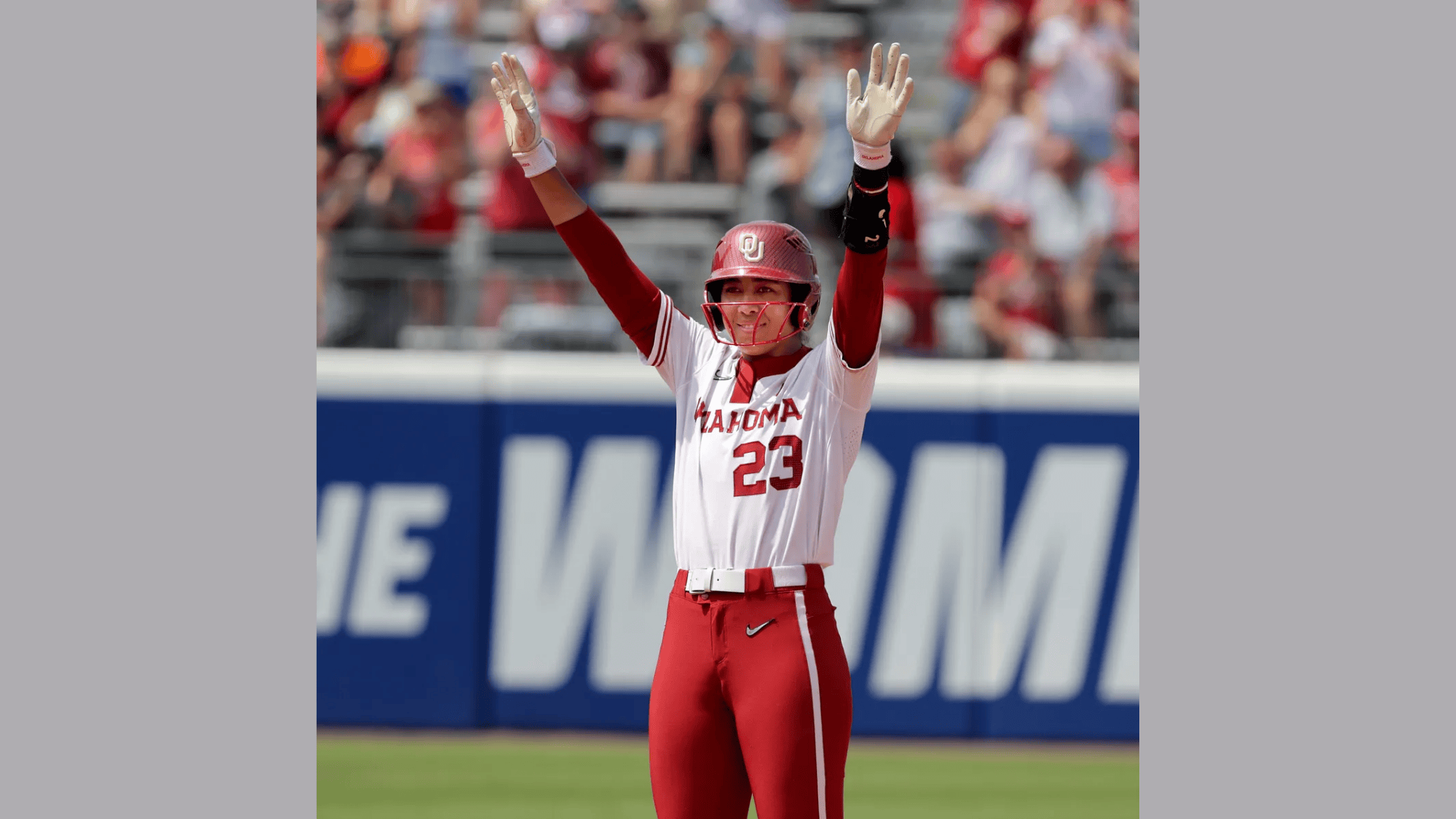

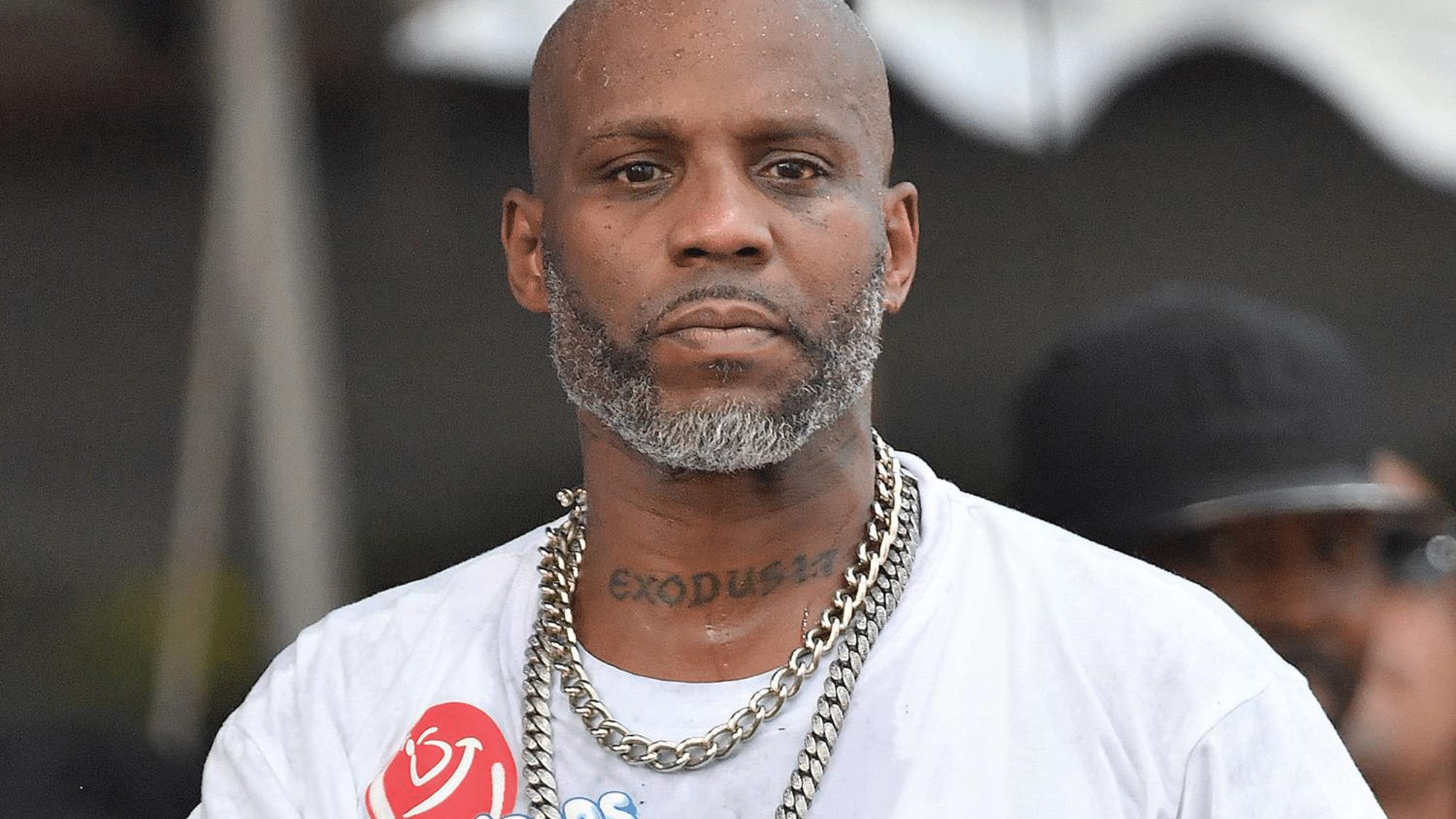

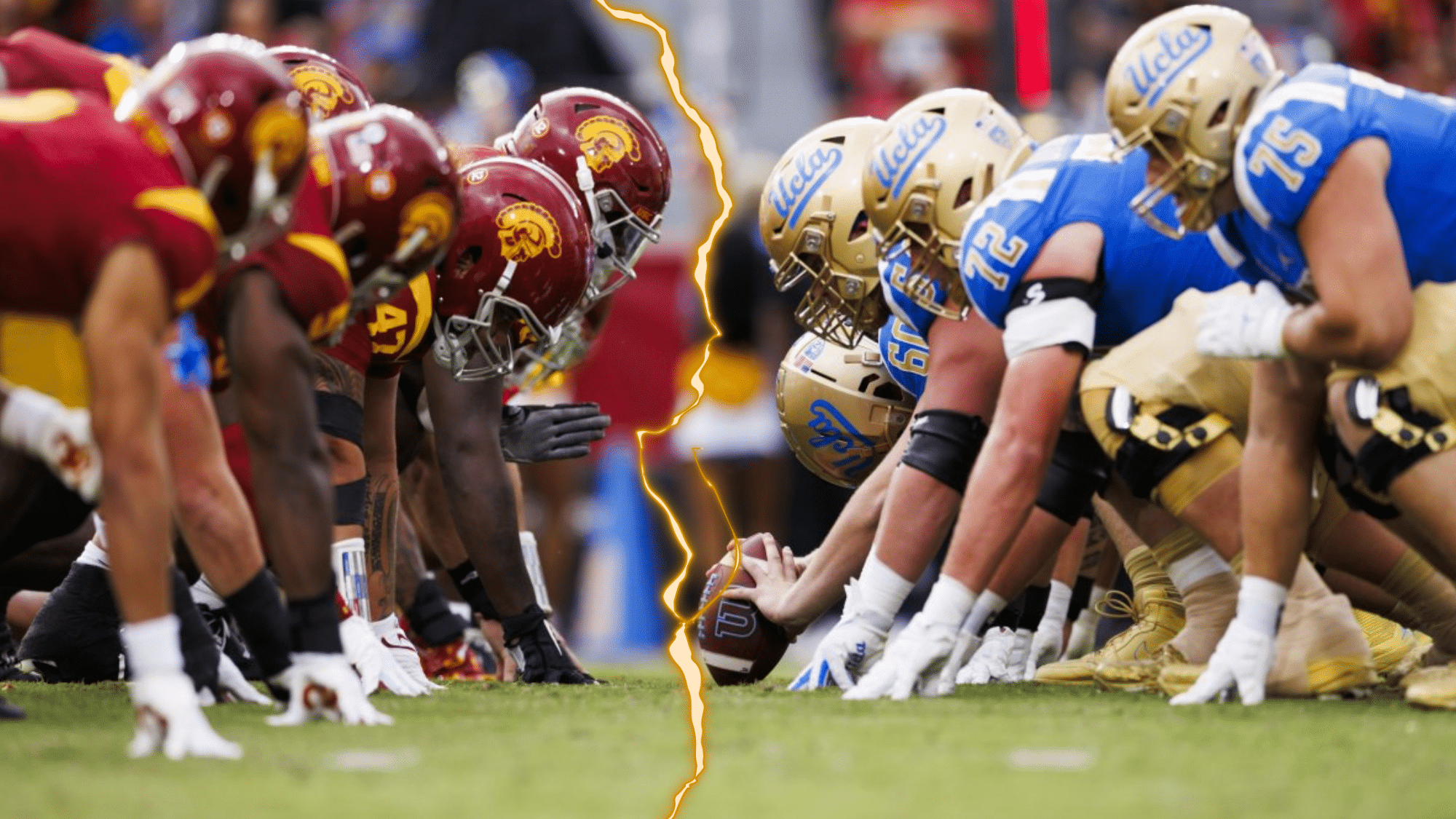

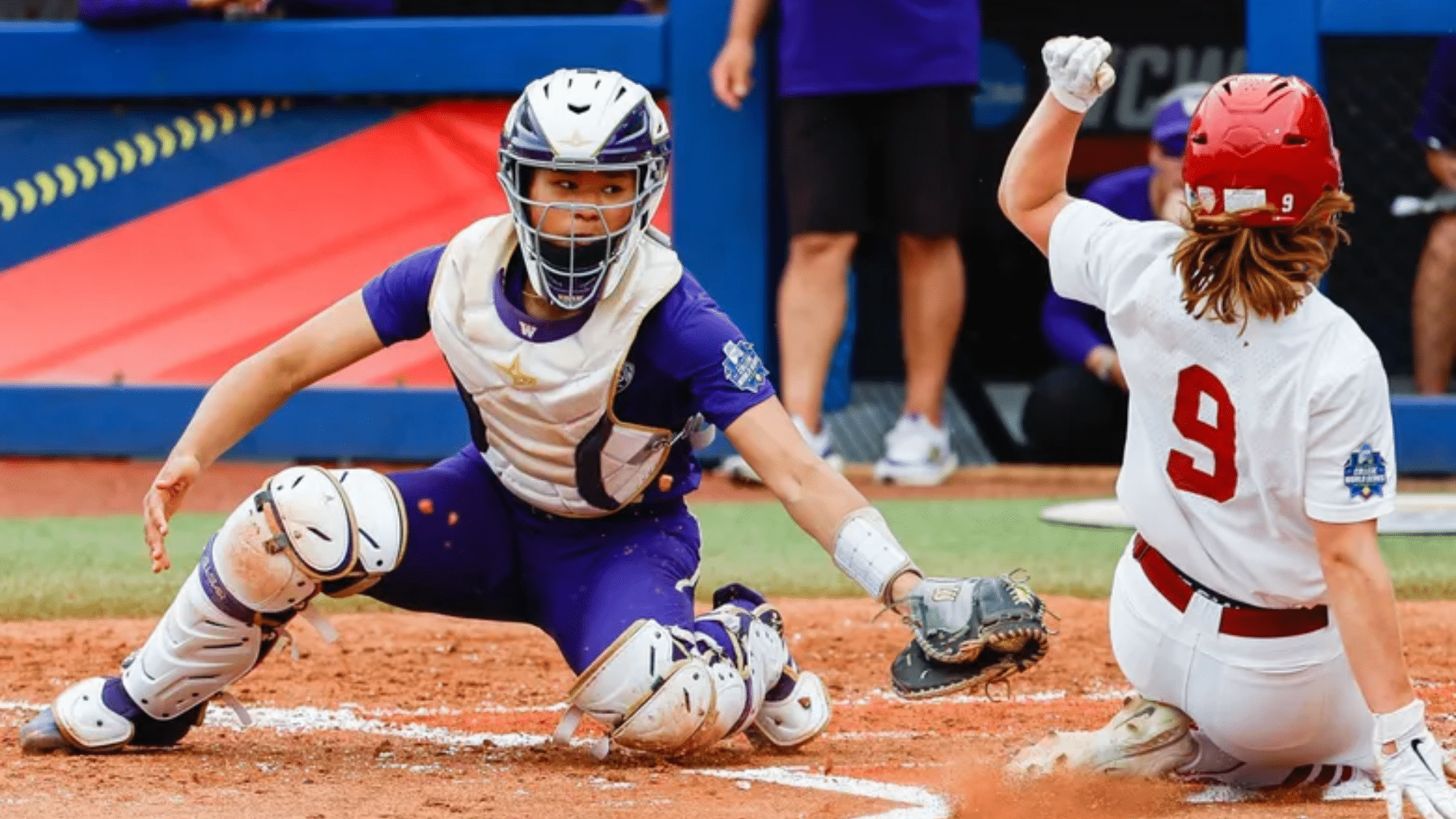

Sports

Some games aren’t just played, they are felt in the soul. These iconic rivalries go beyond the scoreboard, turning into battles of pride, passion, and identity that echo across generations. Whether it’s football in Argentina or cricket in India, these matchups light up stadiums, stir entire nations, and write unforgettable chapters.....

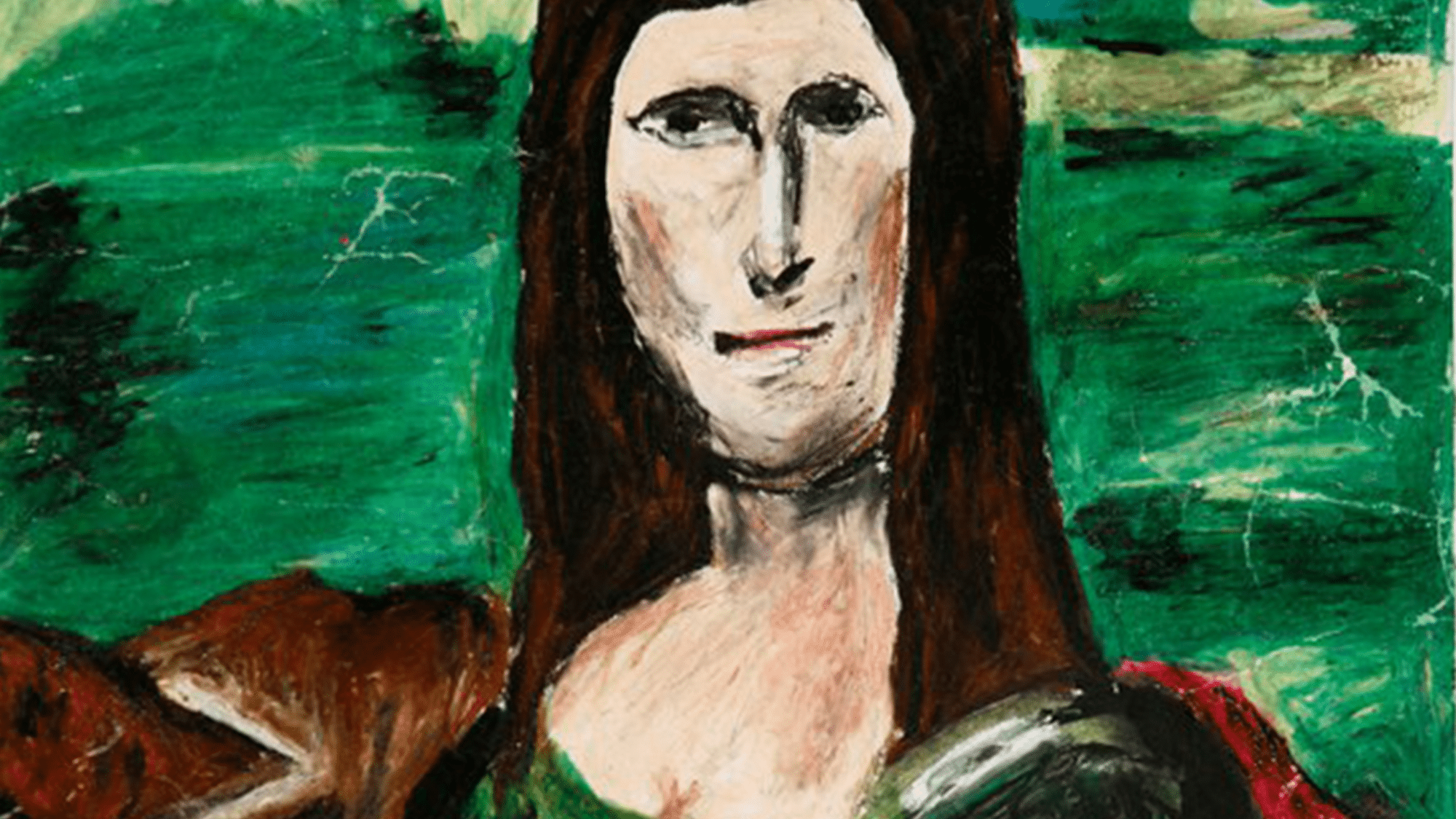

Artists & Artworks

Fall is a magical season filled with vibrant colors, changing leaves, and endless creative inspiration. For teachers and parents, it’s the perfect time to introduce fall art projects that help children explore textures, colors, and nature while developing fine motor and creative skills. If you’re planning a classroom craft or.....

more

Meet Our Team

At CU Independent, we’re committed to delivering real, bold, and honest stories. Get to know the passionate team behind the content!

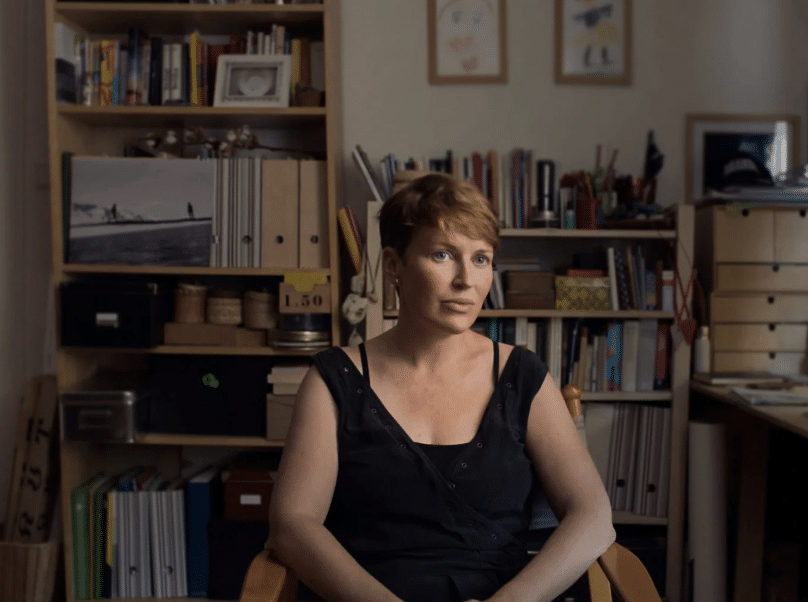

Samantha Lee

(Editor-in-Chief)

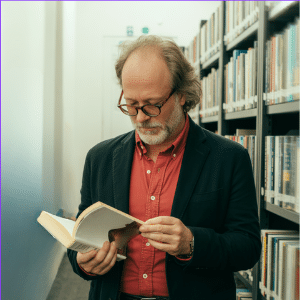

Dr. Alex Thompson

(Senior Features Writer)

Lifestyle

Hootie & the Blowfish is a beloved American rock band, best known for their chart-topping hits in the 1990s. Formed in 1986 in Charleston, South Carolina, the band quickly rose to fame with their unique blend of pop, rock, and blues. Their catchy songs and relatable lyrics connected with fans, making.....

The skin around the eyes is extremely delicate and prone to irritation due to environmental factors, allergies, harsh skincare products, or excessive rubbing. Common signs include redness, dryness, swelling, itching, and sensitivity. Daily habits such as using gentle cleansers, applying hypoallergenic moisturizers, and avoiding rubbing or scratching can help minimize discomfort......

Everything looks clean on the screen until you notice a single cell pulling from the wrong column, and suddenly numbers you trusted have been off for days. It is the sort of quiet error that hides in plain sight, slipping through reviews, right up until someone projects it onto a wall.....

Snoring is often treated as a harmless annoyance or a source of humor. In reality, persistent snoring and disrupted sleep can signal deeper problems that affect your long-term health. When sleep quality remains poor for months or years, it gradually alters metabolism, hormonal balance, and cardiovascular function. Fragmented or shallow sleep.....

As Seen On