Chris Sessions photographing a Charrería event for the Colorado State Fair. (Courtesy of Adam Concannon)

On the second floor of Macky Auditorium in the office of the Center of the American West, photographs featuring men, women, children and their horses line clean, freshly-painted walls. Each photograph is the work of 1997 University of Colorado Boulder graduate Chris Sessions. Though many of the photos are in black-and-white, there’s an indelible sense of life and movement to them, denoting the color that lies beneath the filter.

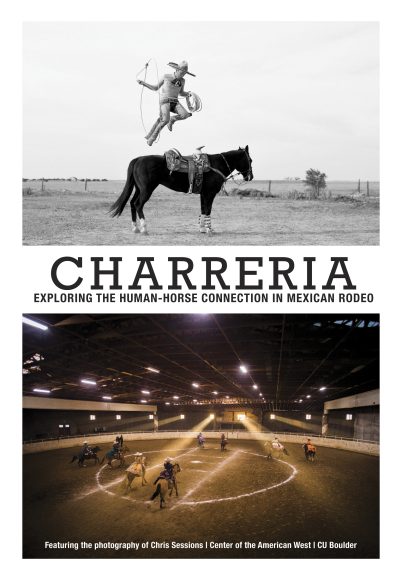

The exhibition is titled “Charrería: Exploring the human-horse connection in Mexican Rodeo.” It features photographs taken over 12 years since Sessions became infatuated with Mexico’s national sport over a decade ago.

“It’s a really colorful community, but it’s more that they give off a sense of pride in their culture,” Sessions said. “That’s what really captured my interest … it’s a timeless tradition.”

Charrería is a robust historical and cultural rodeo tradition whose events resemble the American rodeo. It originally borrowed some equestrian practices from the Spanish charreada, but the artistic flair is also an integral part of the sport. The colorful attire and accompanying lively music and food are all inspired by indigenous Mexican art and differentiate it from American rodeos.

There are about a dozen Charrería teams in Colorado, but the Torres family and their teams, Las Delicias and Flor De Aguileña, lead the pack. Roberto Torres Sr. serves as President of La Federación Mexicana de Charrería en Colorado alongside his children, Roberto Torres Jr. and Naiomy. 25-year-old Carolina Herrera, who was born and raised in Colorado and joined Colorado’s charro community when she was 14, is the state’s Escaramuza Queen, representing the only Charrería event in which women traditionally participate.

Herrera says that among all the things she loves about the sport, her favorite is the connection that comes from this shared celebration of heritage.

“It’s such a family,” Herrera said. “You create so many friendships, you meet new people, you get to go to different parts of the world – to Mexico, to different states here – it brings so much joy.”

Escaramuza, or skirmish, is only one event among ten different suertes, or activities, that charros participate in, but its color, showmanship and athleticism are representative of the rest of the sport.

“To me, being an Escaramuza is culture, it’s history, it’s color, it’s family,” Herrera said. “But the sport itself is an adrenaline rush. It consists of 12 different exercises, kind of like a drill team. We’re galloping at full speed, doing these intricate designs that we’re getting judged on.”

Sessions’ background photographing Charrería in Colorado began as an effort to document the parts of the state’s cultural legacies he felt were at risk of disappearing.

“Around 2010, it felt like the town I moved to Colorado for in the 90s was a lot different than the town it was becoming,” Sessions said. “It was becoming a lot more commercial, and older places that were around were kind of disappearing. So I started photographing county fairs and small towns on the eastern edge of town to document those places before they went away.”

Around that time, Sessions saw an ad for a Mexican rodeo at the Adams County Fairgrounds near Brighton. After attending the event, the spirit of the sport captivated him, and he came back year after year, photographing more and more each time. For Sessions, who is not Mexican nor a charro himself, the Macky exhibition is a culmination of over a decade of building relationships with the Torres family and Las Delicias.

“As a photographer or documentarian, people are kind of wary,” Sessions said. “It took a long time for me to develop my own body of work that I could present to them, for them to welcome me into the community.”

Sessions’ work conveys an air of strength and timelessness, therefore attributing those traits to the larger community he photographs. Herrera said her favorite part of his photography is the eye for detail and the care he puts into representing her culture and community.

“I love his work … he had no idea what this sport is, and he’s gained such a good knowledge about our culture and the significance of it,” Herrera said. “He was able to realize the hard work and the time that we put into it, just to continue our culture here and to continue those Mexican-specific practices – the dress, the attire we have to wear, and everything that goes with it. For him to recognize and see the hard work of it is just amazing.”

Sessions’ exhibition is the Center of the American West’s first in-house art exhibition. The Center, which has been in operation since 1986, serves as an authority about the region of the American West and serves to highlight the West’s role in national and global issues through research, education and programming.

Tamar McKee, the Center of the American West’s director of programs and operations, said the exhibit about Charrería is part of a larger effort to redefine the “cowboy” as larger than its stereotypical narrative of white masculinity in the American West. She said Sessions was the ideal candidate to express this message through his work.

“As an anthropologist, his depth of relationship and knowledge with the community that he’s photographing is just notable,” McKee says. “It’s not just a project for him. It’s the relationships and community he has with these riders … it really speaks volumes for his commitment, and what one can get out of this kind of art.”

McKee says the exhibition came at an inflection point for the organization and marks a philosophical shift moving forward. A year and a half prior to the exhibition’s opening, the Center faced a reckoning when its director and founder, Patty Limerick, was fired after alleged misconduct and the Center’s entire executive board resigned. Though McKee did not comment on those events, she says the exhibition is part of a marked philosophical shift for the Center and a beacon for its path forward.

“The center has always been a hub for bringing people together and making these connections happen both on campus and around the American West, and that spirit is still totally there,” McKee said. “What this exhibit does is it has so many more people sitting at the table in terms of collaboration … It wasn’t just a top-down curatorial approach, which can sometimes happen in academia … we instead wanted to make it more of a roundtable and a co-creative experience, which is continuously unfolding.”

Chris Sessions, Carolina Herrera and Tamar McKee at the Center of the American West. (Courtesy of Ryan Lueck)

The focus of the exhibition is the connection between humans and horses, which is a central part of McKee’s academic research and career. She said the connection between humans and horses is an enormous part of the story of the West and a signifier of the symbiotic relationship between humans and what she calls the “greater-than-human world.”

“Whether you were following horse herds or coming in on horseback or horse-driven carriages, our human ability to come into this land and be a part of this land is so much in relationship with animals, be they wild or domestic,” McKee said. “[The West] is a place that really reminds us that we’re in an order of things, we’re not all the things.”

Herrera says the human-horse connection is vital for her athleticism and is present in every part of her sport.

“These horses have to start from zero – they have to get trained, they have to get to the point where you’re able to put them inside of an arena to work with other horses, to be around other girls, to be around other heartbeats,” Herrera said. “You’re trusting your partner, which is the horse, to keep you safe and to accomplish what you’ve been training for.”

Sessions says that the intuition involved in the connection between the Charrería athletes and their horses is something that connects him and the community to their respective artistic mediums.

“It’s really hard to put into words what the human-horse connection is, but it’s something that I have seen and experienced as I take the pictures – it’s almost more of an intuitive process,” Sessions said. “It’s similar to the way that I approach my own photography – it’s based on that intuitive motivation to capture the right moment.”

“Charrería: exploring the human-horse connection in Mexican Rodeo” is on display through October 17. It’s free to enter, located in the Center of the American West at the second floor of Macky Auditorium, and open Monday through Thursday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Editor’s note: This story originally misstated who runs the Charrería state organization. It has been updated.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Lauren Hill at lauren.hill-2@colorado.edu.