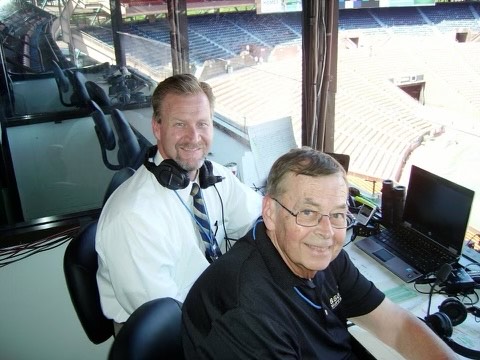

Mark Johnson (left) and Larry Zimmer (right) inside the press box at Folsom Field. (Courtesy photo Mark Johnson)

For 20 years, Mark Johnson has called every tackle, touchdown and timeout at Folsom Field. He’s done so from a room overlooking the stadium called the Larry Zimmer press box.

The box is named after the legendary University of Colorado Boulder football and men’s basketball announcer who died in January. But when Johnson first came to CU Boulder in 2004, he spent 12 years calling games with Larry Zimmer himself.

Johnson told the CU Independent he remembers the late announcer’s legacy of compassion, culture and knowledge he left behind after calling play-by-plays for 42 football seasons.

Zimmer called the glory days of Colorado football. He painted the picture of Rashaan Salaam’s Heisman campaign and became the voice behind the 1990 national champions. He watched five Ralphies run during his time. But in 2004, the university’s athletic department felt it was time for a switch and brought on Johnson to call games from the first chair.

Johnson came to CU Boulder from Syracuse University, where he called play-by-play for their football and men’s basketball teams for three years. Before he was the voice of the Orange, he announced games for Illinois State University for four years and spent two years calling at his alma mater, the University of North Dakota.

He came into the job knowing how to call a game, but his time at Syracuse didn’t teach him the history and culture surrounding CU athletics. From the second chair in the press box, Zimmer took Johnson under his wing to become the next voice of the Buffaloes.

“He showed me respect and I showed him respect as well. I would have been pretty darn stupid to not come in and understand his history and what this program is all about,” Johnson said. “He educated me for many years early on. Even though I’ve now been doing it for 20 years, I can’t tell you how many times I would make a phone call to him asking, ‘How does this man or woman play a role in Colorado athletics history and what the program has been about.’”

Johnson said Zimmer advocated for the fans to get used to the transition when he first arrived, and had been nothing but welcoming to him.

“[The] first thing he said to me was, ‘Listen, I just found out about this. You’re coming in to do what I’ve been doing for a long time, and now I’ll be working alongside you … this is never going to be a problem between the two of us.‘“ Johnson said, recalling his initial meeting with Zimmer.

Mark Johnson (left) and Larry Zimmer (right) at the University of Utah. (Courtesy photo Mark Johnson)

The new co-workers were different in nearly every way. Johnson, a self-described cowboy, physically towered over Zimmer, and his booming baritone voice was a stark change from the slow southern drawl fans had been accustomed to for 32 years.

“That voice becomes part of the soundtrack of Colorado athletics,” Johnson said. “So that [change] could be a little bit shocking for people at times. There were similarities, but we were going to approach it differently, we were going to sell it differently, we’re going to have a different sense of humor. And so it took a while for people to understand that.”

When calling games, Johnson said the pair just got each other, which also helped fans understand Johnson’s new role. But outside the press box, Zimmer and Johnson differed wildly in their interests and personalities.

“Larry was very deep into the arts. He loved opera and he loved theater. And you want to talk about our styles, the big differences. We came from very different worlds in that regard,” Johnson said. “Larry was always trying to get me to understand opera and I’d say, ‘You know no matter what I’m always gonna appreciate what you’re playing for me.’ It never made a whole lot of sense to me, I think he got a kick out of it.”

Their friendship was evident when Johnson remembered his time with Zimmer. When reflecting on their interactions, Johnson said the words respect and integrity eight times each.

Many of Johnson’s memories of his and Zimmer’s shared past took place on Friday nights, ahead of a Saturday game.

According to Johnson, when they were on the road for away games, there was a standing steak dinner on Friday nights. Zimmer would round up statisticians, engineers and sideline reporters and talk to them — not as colleagues but as people.

Whether it was with 10 people or 20, Zimmer would invite whoever he could to join the tradition.

“The socialization moments were so important to Larry. He was such a people person, and those were the times when he loved to talk to us as humans, not coworkers,” Johnson said.

Mark Johnson (left) and Larry Zimmer (right) inside The Larry Zimmer press box at Folsom Field. (Courtesy photo Mark Johnson)

Johnson said he’s worked to carry this culture of compassion into a new era of Colorado football, even after Zimmer retired in 2016.

“We had some wonderful conversations talking about the respect that we had for one another. He said, ’Mark, it could have been ugly. We’ve seen this business as competitive as it is. We’ve seen it a number of times. Those things will happen and rarely do they work out well,’” Johnson said. “This one worked out well because Zimmer, being the older man at that point in time, he’s the one that set the tone.”

In 2009, Zimmer earned the National Football Foundation’s Schenkel Award and was inducted into the Broadcast Professionals of Colorado Hall of Fame that same year. He’d be inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame a year later and the CU Athletics Hall of Fame in 2012.

But beyond his talent, Johnson said he hopes people will remember the kindness Zimmer had for his colleagues and his friends.

“One thing maybe people didn’t fully appreciate was that he was a great guy,“ Johnson said. “The warmth that he had and how he loved. That’s something that I don’t think people fully appreciate about Zimmer’s legacy.”

Zimmer died on Jan. 20, 2024. He was 88.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Kiara DeMare at kiara.demare@colorado.edu.