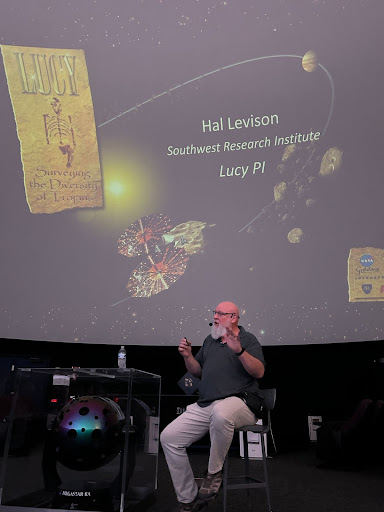

NASA’s principal investigator, Hal Levison, presents on the Lucy mission at Fiske Planetarium on Thursday, Oct. 26, 2023. (Michaela de Oliveira Olsen/CU Independent)

On Oct. 26 and 27, the University of Colorado Boulder’s Fiske Planetarium hosted a presentation about NASA’s Lucy mission. The spacecraft, launched in October 2021, is on a 12-year mission to study asteroids orbiting Jupiter.

The Lucy spacecraft is set to encounter its first main-belt asteroid on Nov. 1. The principal investigator for the NASA mission, Hal Levison, and the deputy principal investigator, Simone Marchi, joined Fiske Planetarium to update to the Boulder community.

“Lucy is mainly a Colorado endeavor,” Levison said.

Downtown Boulder scientists contributed to much of the research that went in to the Lucy mission, operations of south Denver’s United Launch Alliance assisted with the launch and Lockheed Martin Denver worked on the trajectory.

Levison and Marchi currently work as planetary scientists at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder focusing on the dynamical evolution of solar systems and overseeing important aspects of the Lucy mission.

Levison began the presentation with a projection on the Fiske dome. He discussed the upcoming main belt asteroid encounters, Trojan asteroid types and Lucy’s efforts to understand the diversity of bodies in space and their formation.

Marchi said the mission has a “rich selection of targets that have never been explored.” Scientists will use the data collected to test theories regarding early planetary formation.

The presentation focused on discussing the development of the unique space technology and the complex trajectory that allows NASA to explore a record-breaking number of asteroids.

Lucy is the first spacecraft to explore seven Trojan asteroids that share an orbital path with Jupiter. The name comes from the Lucy fossil that archaeologists discovered in Ethiopia in 1974, which has served as an important source for evolutionary explanations of the human species.

“[The] analogy is that we think that the Lucy mission will be equally important to understand the evolution of the solar system,” Marchi said.

The mission is also significant because it is the farthest-flung solar-powered spacecraft. The spacecraft has selective equipment for the flyby encounters, including telescope imagers to capture high-resolution pictures of the asteroids’ surfaces. Additionally, scientists use spectrometers for collecting data that will assist with information on material composition and information regarding surface temperatures.

Marchi explained that the spacecraft has a terminal tracking system that allows the spacecraft to autonomously “define where the target is… to boost the scientific return of every single flyby.”

Partners of the mission also promoted a program through the L’SPACE Academy, where students can get involved as ambassadors for the mission and receive training to teach the public about the spacecraft.

On Nov. 1, Levinson and Marchi plan to celebrate the first encounter of the Dinkinesh asteroid at Lockheed Martin Denver and await the first signal from the spacecraft.

Then, they will return to the Boulder office to gather with scientists and others involved with the project and take a first look at the data with “great expectation and great excitement,” according to Marchi.

“Expectations are nebulous,” Levison said.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Michaela de Oliveira Olsen at mide8242@colorado.edu