Sarah Ortegon and Michelle Grimes read their parts for Marty Strenczewilk’s play the “Master Plan” at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, Colo. on Oct. 10, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

Editor’s note: A version of this story was originally written for the College of Media, Communication and Information’s News Corps program.

In the play “Master Plan,” a Native American woman named Jodi is forced to play into stereotypes about her culture to raise money for her charity Indigehope, which provides resources for reservations across the country.

Claire, Indigehope’s white co-chair, wants Jodi to put on a feathered headdress and moccasins to give a speech to potential donors about the struggles of growing up on a reservation. In this scene, the tension builds as it becomes apparent that Jodi likely grew up hundreds of miles from the closest reservation.

Yet, Jodi is surprisingly unhesitant to do as Claire asks. Why?

Because she knows the donors’ money will be able to provide consistent running water for many reservations.

The play “Master Plan,” first performed at the Dairy Arts Center on Oct. 10, 2022, explores the dangers of tokenism and the reasons why some minority people face this issue.

Marty Strenczewilk writes poetry for “Reflections on Thanksgiving: The Native Perspective” at Ozo Coffee in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 23, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

While crafting this play about Indigenous representation, playwright Marty Strenczewilk faced one major problem every time he sat down to work: he didn’t fully understand where he comes from. Of Ojibwe heritage, Strenczewilk would prefer to craft his material with his people’s history and culture in mind; however, much of this identity has been erased.

“Everyone thinks we’re ‘Indians,'” he said in an interview with the CU Independent. “There’s no ‘Indian’ history, just like there’s no European history. There’s Ojibwe history, Seminole history, Dene history and Lakota history. They’re all different. It’s just like how there is Italian history and British history. You can’t go get an Ojibwe history book.”

One of the main reasons that the history of Native American peoples often gets generalized is due to the U.S. government’s extermination of many tribal cultural practices. This took place during the implementation of the system of Native American boarding schools from 1819 to 1969. Often kidnapped and taken to these schools, Native American children were forbidden from speaking their mother tongues and practicing their religions. Historians estimate that hundreds of thousands of children were put into these schools, though the exact number is not known.

Marty Strenczewilk reads his poetry for “Reflections on Thanksgiving: The Native Perspective” in the Sacred Space at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 26, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

“My grandmother was given to a white family when she was born,” Strenczewilk said. “Her four older brothers were sent to boarding schools, and the boarding school system destroyed them. My grandmother knew a lot of our history and culture, so she could talk to us. [The history] is super dramatic.”

After leaving the schools, the children often had no remaining connection to their heritage and culture, and thus they couldn’t pass their history on to future generations. According to the Indigenous Language Institute, more than 300 Indigenous languages were once spoken in the U.S. Even with language restoration efforts, it’s estimated that there will be no more than 20 Indigenous languages spoken by the year 2050.

Robert Martinez’s “Trick Shot” at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 26, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

“In general, most people don’t understand what it means to be ‘Indian,'” Strenczewilk said. “I didn’t go to a boarding school, and I didn’t get pulled away from my family. Those things didn’t happen to me. But all of [what happened to my family in the past] has worked its way down into my life, right? The challenges my grandmother and grandfather faced trickled down to my mother, and then it trickled down to us.”

Thus, without knowing the full history of their individual tribes, many Native American creatives struggle to move beyond stereotypical representations of their own cultures and people.

Strenczewilk examines these themes in his play, “Master Plan,” particularly the tension between following traditions and playing into stereotypes. He said the play was, in part, inspired by his experiences owning a video game company named Splyce, where he felt expected to represent all Indigenous people.

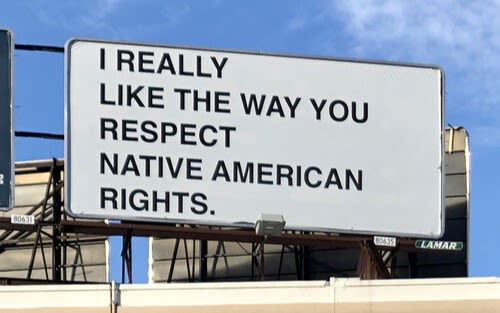

One of Anna Tsouhlarakis’s billboards in downtown Colorado Springs, Colo. (Courtesy of Anna Tsouhlarakis)

This tension of what it means to be a stereotypical Indigenous creative can also be seen in the work of multimedia artist Anna Tsouhlarakis, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and a member of the Navajo Nation. Her work aims to redefine the expectations of what Native American art is supposed to be or expected to look like.

Tsouhlarakis’ most recognizable work is two billboards in downtown Colorado Springs, created during her art residency at Colorado College in 2019-2020. The billboards consisted of black capitalized sans serif text on a white background. They read: “I really like the way you respect Native American rights” and “It’s great how you acknowledge that Native Americans are still here.”

“I started seeing work that didn’t necessarily neatly fit in the box of what culture people came from, [such as] Asian American, Latino American, Latin American or Black American art,” said Tsouhlarakis in an interview with the CU Independent. “That’s what really compelled me to start doing the type of work that I do. Twenty-five years ago, there weren’t a lot of native women working with non-narrative, non-linear videos or installations.”

One of Anna Tsouhlarakis’s billboards in downtown Colorado Springs, Colo. (Courtesy of Anna Tsouhlarakis)

Gregg Deal, a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, is another multimedia artist who has dealt with the pressure to conform to the expectations of Indigenous artwork.

Like Tsouhlarakis, Deal’s art is mostly contemporary and conceptual. His murals, which can be seen in Denver, Colorado Springs and Boulder, would more accurately fall under the category of pop art. The artwork is bright and colorful and often satirizes pop culture icons like Bansky’s “Girl with Balloon” and the album cover of David Bowie’s “Aladdin Sane.”

“As an artist, I’ve found that the only way to function as an artist is that you have to work within the bounds of what Western culture expects you to do,” he said in his TedTalk, “Indigenous in Plain Sight.” “They expect us to be painting cowboys and Indians. … And as a result of that, we’re one of the few subcultures in the art world that is actually being controlled by a Western buyers market that decides whether or not there’s value with our stories.”

A print of Gregg Deal’s “ZiggIndigenous” (Courtesy of Gregg Deal)

Deal’s sentiment is reflected in several parts of the Strenczewilk’s “Master Plan.” For example, Jodi comes to the realization that Indigehope’s donors will only listen to her when she plays into their preconceived notions of Indigenous people.

However, what “Master Plan” ultimately uncovers is that the onus to help marginalized communities falls on people with privilege like Claire and not on marginalized people like Jodi.

For Strencezewilk, this kind of action was reflected in real life last year, when the Dairy Arts Center established the Creative Nations’ Sacred Space. When Strencezewilk and the other Indigenous artists established the Creative Nations Collective, the Dairy reached out to them and offered them the Sacred Space, a space to perform, practice and exhibit their work. This space opened on Sept. 16, 2022.

A young patron looks at artwork in the Homelands exhibit in the Dairy Arts Center’s Sacred Space in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 26, 2022. (Courtesy of Helen Flock)

“This is [the Dairy Arts Center’s} way of [modeling] leadership and accountability for other arts organizations,” said Strencezewilk, the managing director for the collective. “It says, ‘If you believe in supporting Native arts, a plaque on the wall for land acknowledgment is not enough.’ That’s the very, very teensy tiny tip of the iceberg.”

“Now, how do you become an ally?” he continued. “As I say, allyship is when you truly have to sacrifice something. If you don’t sacrifice anything, you’re not an ally. You are honestly virtue signaling as one, right? So the Dairy has sacrificed something. They took a spot in their building where they made revenue, removed that revenue and gave it to us.”

Jaycee Beyale’s “Ádaaní – They are speaking” at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 10, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

For Melissa Fathman, the executive director of the Dairy Arts Center, the organization needed to support indigenous artists in a tangible way. She believed that a plaque on the wall was not enough.

“It’s about supporting the Indigenous arts community, but it also acts as a model for how other arts organizations can be,” she said. “When I wanted to acknowledge the land, I kept thinking that a plaque is pitiful. It goes in that category of thoughts and prayers. [I thought] we could do something.”

When deciding on how to go about creating the Sacred Space, it became clear to Fathman that the center was going to have to do much more than just create an Indigenous art exhibit.

Anna Tsouhlarakis’ exhibit “Her Second Story: Blood and Water” on display at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, Colo. on Nov. 10, 2022. (Courtesy of Jazmyne Bernal)

“As a white-led organization trying to make space for inclusion and diversity, it feels hollow to program something from someone else’s culture,” Fathman said. “It’s like setting the table and inviting people to the table. You bring the food you want to bring or talk about the things you want to talk about. Our role is to provide the space and the support.”

The inclusion of Indigenous voices in the curatorial process is evident in the Sacred Space. A lot of the art in the exhibit is contemporary and meant to push against the public’s preconceived notions of Indigenous art, as well as to remind the public that Indigenous people don’t exist solely in the past.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Jazmyne Bernal at jazmyne.bernal@colorado.edu.

Contact Guest Writer Helen Flock at helen.flock@colorado.edu.