“The Nun Ryonen (Ryonen-ni)” from Famous Women of Past and Present (Kokon meifuden) (1864), Utagawa Kunisada and Ryūtei Tanehiko (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

“Why have there been no great women artists?” wrote Linda Nochlin in her influential 1971 feminist art history essay.

Throughout history across the world, women have faced cultural, social and institutional barriers to becoming great artists in patriarchal societies. Despite their talent, they have been systematically underrepresented and excluded from the male-dominated canon of art history.

This is especially true in premodern Japan, during the Edo Period (1603-1867), where women occupied a subservient role dictated by “The Three Obediences” of Confucianism — the principle that women must obey their father, husband and son. However, despite these strict gender roles and societal restrictions, some notable women overcame these barriers to leave their mark on Japanese art history.

Their legacy lives on in the Denver Art Museum’s latest exhibition, “Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection,” which opened on Nov. 13.

The exhibit consists of 100 works of painting, calligraphy and ceramic by about 30 artists from the 1600s to the 1900s, including Kiyohara Yukinobu 清原雪信 (1643–1682), Ōtagaki Rengetsu 太田垣蓮月 (1791–1875) and Okuhara Seiko 奥原晴湖 (1837–1913).

“Breaking Waves in the Pines (Shōtō)” (late 1900s), Murase Myōdō (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

“It is an exploration of how art can be a vehicle of empowerment, a form of taking up space as a woman in a patriarchy, and how these artists, through their art, inscribed themselves into our present,” said Dr. Einor Cervone, associate curator of Asian art at DAM and co-curator of “Her Brush.”

“Her Brush” is the largest exhibit in the U.S. dedicated to premodern Japanese female artists in over three decades — since Patricia Fister’s exhibit “Japanese Women Artists 1600-1900” at the University of Kansas’ Spencer Museum of Art in 1988.

Many of the works in “Her Brush,” donated from the private collections of Dr. John Fong and Dr. Colin Johnstone in 2018, will be publicly displayed for the first time in centuries.

Many of these premodern female artists have received little or no recognition — even in Japan. This is a result of a variety of historical and contemporary factors, including the lack of archival documents about their lives and legacies and the anti-feminist bias present in many art institutions in Japan.

After a feminist wave shook up Japan’s art world in the 1990s, a widespread conservative backlash began in the early 2000s, making it increasingly difficult to use the words “feminism” and “gender, according to Stephanie Su, an assistant professor of Asian art history at the University of Colorado Boulder. Su’s research includes global modernism, historiography and the history of collecting and exhibition in modern Japan and China.

On Nov. 3, Su appeared alongside Cervone and Patricia Graham, a research associate from the University of Kansas Center for East Asian Studies, for a panel discussing DAM’s “Her Brush” and the role of women artists in the art world from the seventeenth century to the modern day. The panel, titled “Remarkable Japanese Women Artists and Craftmakers in a Male-Dominated World,” was hosted by CU Boulder’s Center for Asian Studies and the History Department.

“A lot of institutions don’t like the term feminism,” Su said. “They think adding a gendered perspective is imposing Western ideas on Japanese culture. Secondly, many [contemporary art critics] think that there are no great women artists [from the past]. They believe it’s a historical truth. As a result, a lot of female scholars feel their work is not valued.”

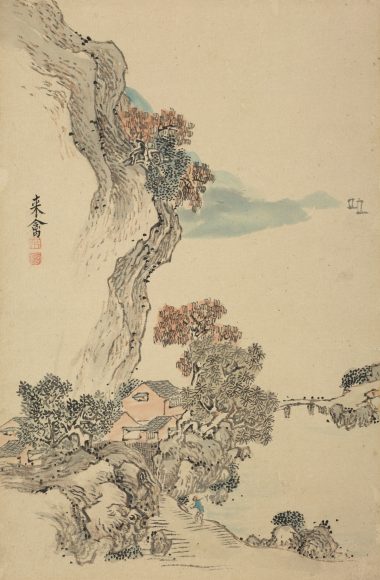

“Autumn Landscape” (late 1700s), Kō (Ōshima) Raikin (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

Despite this prejudiced perspective in many of Japan’s mainstream institutions, art historians and curators in America and other countries around the world have been working to challenge the gender status quo of Japanese art history.

“Her Brush” marks a significant milestone for this movement. The exhibit, split into seven themed sections, contextualizes the work of female artists based on their identity and social class, rather than by theme or era. The first section, “The Inner Chambers” (ōoku 大奥), illustrates how upper class women born into elite and wealthy households received training in the “three perfections” (poetry, painting and calligraphy) to entertain at court and to be a suitable companion for their future husbands. Though most were amateur artists, a few exceptionally talented and resourceful aristocratic women became professionals.

Another section, “Taking the Tonsure” (shukke 出家), presents the work of Buddhist nuns. In the Edo period, though they still had fewer rights than monks, nuns enjoyed greater social status and autonomy than laywomen. This enabled them to freely pursue their passion for art making. The other sections interweave various identities, including women born into the artist trade as “Daughters of the Ateliers,” the intellectuals of “Literati Circles” (bunjinga 文人画) and the musical performers (geisha 芸者), actors and sex workers in the “Floating Worlds” (ukiyo 浮世), state-sanctioned entertainment districts.

“Flowering Plants of the Four Seasons” (1898), Okuhara Seiko (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

Despite the diversity of these women’s experiences, their perseverance and resourcefulness are a common thread across social classes and time periods.

“Many of the artists [in this exhibit] show what it means to live life without barriers,” Su said. “Their stories can be very inspiring for everyone, especially for those who have faced a lot of challenges in life.”

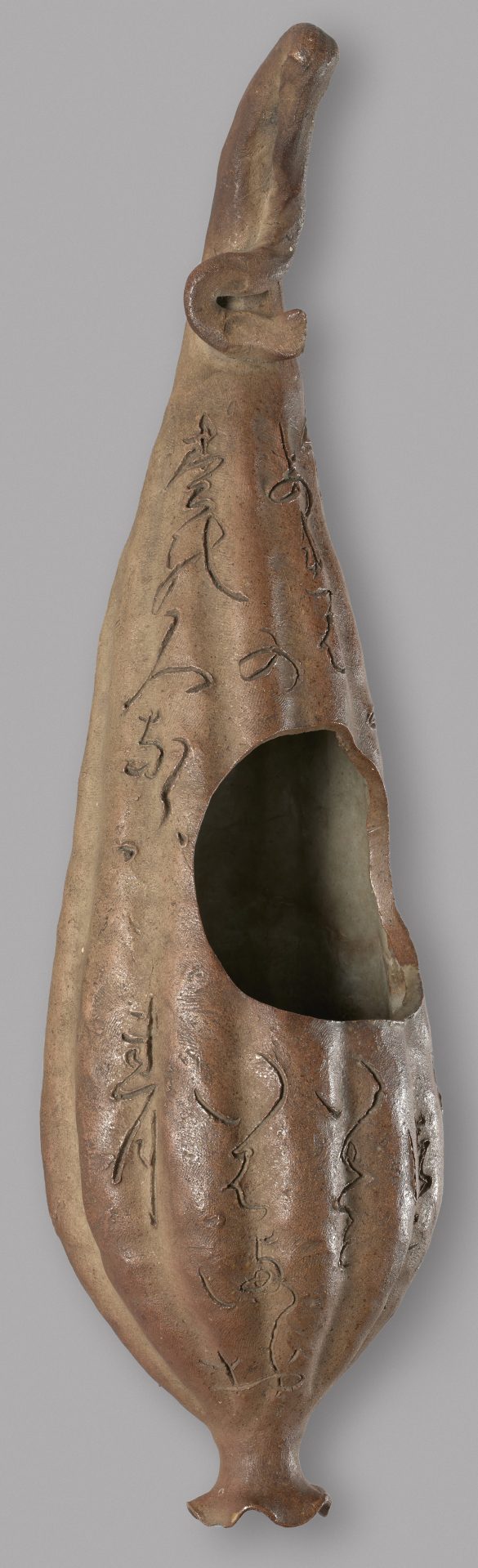

Buddhist nun Rengetsu, widely regarded as one of the greatest Japanese poets of the 19th century, faced many hardships throughout her life. At the age of 13, she lost her adoptive brother and mother. Over the next 30 years, most of her close family members died, including her four children, two husbands and two adoptive siblings. When her adoptive father died, she left his temple and began selling pottery decorated with her poetry to support herself. Her masterful work was soon in great demand. During her lifetime, it was said that every household in Kyoto apparently had at least one of her pottery works.

The section “Taking the Tonsure” reflects the significance of Rengetsu’s legacy. The centerpiece of this section, Rengetsu’s “Travel Journal to Arashiyama (Arashiyama hana no ki)” from the 1800s, features freely brushed poetry, interspersed with minimalistic illustrations. This journal offers an intimate glimpse into her personal life. Nearby, an imagined portrait of “Rengetsu Working in Her Hut” appears, painted 60 years after the artists death by Suganuma Ōhō 菅沼大鳳 (1891–1966) as an homage to her legacy.

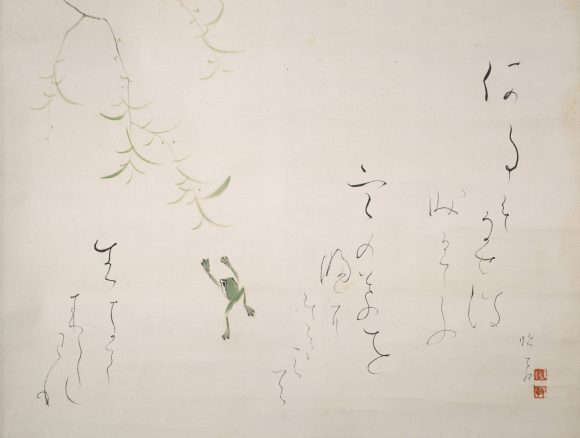

“Willow and Frog” (mid-1900s), Ōishi Junkyō (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

This section also features the works of Ōishi Junkyō 大石順教 (1888–1968), known as the Mother of the Disabled, who established herself as a missionary, social worker and talented artist. Junkyō received recognition for her mouth-drawn paintings, a style she adopted to accommodate being a double arm amputee — a tragic result of an attack by her foster father when she was teenager.

In “Her Brush,” Junkyō’s work “Willow and Frog” from the mid-1900s depicts the uplifting story of courtier Ono no Tōfū 小野道風 (894–964). After failing to get a promotion seven times, Tōfū wanted to quit — until he found inspiration in a determined frog, which was trying to jump onto a willow branch. The frog failed seven times, before finally succeeding on its eighth attempt, inspiring the courtier to persevere and eventually become a successful statesman.

The exhibit’s final section, “Unstoppable (No Barriers),” features another Buddhist nun with an inspirational story: Murase Myōdō 村瀬明道尼 (1924-2013). Myōdō, who lost her arm and the use of her right leg in a traffic accident in her late 30s, refused to let physical limitations hold her back from her creative pursuits. During her recovery, she taught herself to use her left hand to craft masterful calligraphy. Her work “Mu (no, or nothingness)” and “Kan (barrier)” (無関), featuring the two characters painted on opposite sides of the table screen, offers a visual representation of expanding beyond physical limits.

The inspirational stories of these three women and others can be found on collectible tanzaku (colorful poetry slips), designed by Denver-based artist Sarah Fukami, in several locations throughout the exhibit. Traditionally, tanzaku, written by men and women from many social classes, were given as gifts — or hung on bamboo branches during festivals for wishes to come true. Fukami’s modernized tanzaku, intended to appeal to a younger audience, are formatted similar to a trading card with the artist’s portrait and a short biography in English and Spanish.

“We’re hoping this can be exhibition for people of all ages,” said Karuna Srikureja, the associate interpretive specialist for DAM’s Asian art department. “Maybe we can spark [interest] in young girls. They can become huge fans of Japanese women artists and grow up with those figures in their minds.”

Poem Slips (tanzaku) (1700s to 1900s) (Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum)

Another interactive element of the exhibit includes a large projection screen on the final wall, inviting visitors to create their own ephemeral calligraphy.

“We are trying to convey the notion of the brush as an extension of the body,” Cervone said. “We want to help visitors embody and physically, viscerally experience the idea of leaving a mark through art.”

Through this, Cervone hopes that visitors will be able to connect with the power of the brush as a force for self-expression and agency — just as these Japanese women did centuries ago.

“This is a way to inscribe yourself into our presence,” Cervone said. “It’s a remarkable, gutsy act of taking up space as a woman. This notion of leaving a brush stroke is a way of deciding that your artistic voice is important enough to be heard.”

“Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists the Fong-Johnstone Collection” will be on view from Nov. 13 through May 13, 2023 in the Martin Building’s level 1 Bonfils-Stanton Gallery at the Denver Art Museum. The exhibit is included in general admission.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Izzy Fincher at isabella.fincher@colorado.edu.