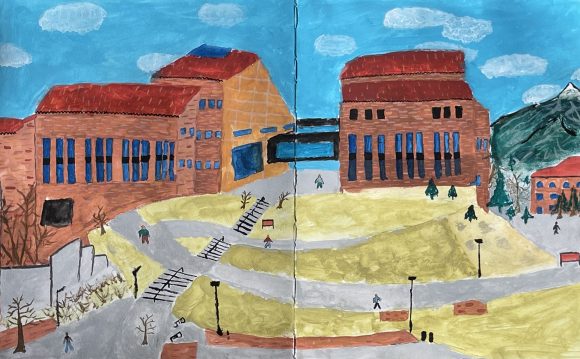

CU Engineering student Alakh Patel’s sketchbook shows a painting of CU’s CASE Building from his perspective in the VAC [Courtesy of Alakh Patel]

Reeling from the pandemic, CU Boulder’s art community has undergone various transformations. Undergraduates, educators, graduate students and curators alike encountered both creative inspiration and devastation during some of the pandemic’s most tumultuous times. Artists accustomed to intimate studio hours were confined to their living spaces. The average student sought refuge in crafts. The practice of art as self-therapy skyrocketed.

Art has a known history of healing. In as early as 1942, traditional arts practices were used to revive populations of ailing tuberculosis patients. It was here that the term art therapy was first conceived.

When Hurricane Katrina devastated the southeastern U.S. in August 2005, art therapy through crayon drawings helped address the impact of trauma on youth populations. As recently as March of 2022, diverse art therapy practices in Boulder, Colo. are being actively implemented for community members impacted by the Marshall Fire.

For students like art history master’s candidate Emilie Luckett, the pandemic has abstractly redefined the therapeutic elements of the arts community.

Luckett’s embroidery artwork titled “Inclusivity of Femininity” [Courtesy of Emilie Luckett]

Luckett’s embroidery artwork titled “You Don’t Tell Me Who I Am” [Courtesy of Emilie Luckett]

From majors to minors, amateur crafts and graduate-level degrees, university students have used the pandemic to both diversify and explore their creative outlets. Student exhibitions, curations and individual practices at CU Boulder are thriving in 2022, but the journey has been far from smooth for many.

“I think it’s so important for bridging gaps between communities or people. I really think it teaches empathy, understanding, sympathy and all those things,” said Luckett. “So, that’s what I love most about art. It can teach us. I always say art is a form of communication. It’s just visual.”

Discovering and exploring new practices

With restricted access to resources, human interaction and the outdoor world, university students found their artistic styles adapting to the limited nature of pandemic lifestyles. From color to medium and subject, the pandemic reshaped how students interacted with their bodies of work. While the world was situated in a grim state of disaster, the arts became a sanctuary of creative exploration for some.

Allie Popp, a senior in art practices and psychology, was sent home prematurely during her sophomore year at CU because of the pandemic. With art materials abandoned in Boulder for ease of travel, Popp’s usual medium of ink transitioned to that of colored pencils.

“I felt a lot less excited to create,” Popp recalled. “I thought, ‘what do you want to do besides sit in your room and do nothing?’ So, I decided that I was gonna start trying to color.”

“I definitely started to use my colored pencils a lot more, just because I needed some color in my life,” she added.

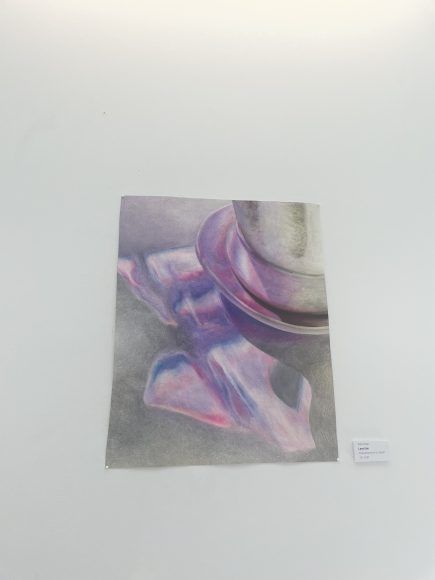

Popp’s multi-media piece titled “Rainbow Brain” on display during her March 2022 exhibit. [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

Popp’s multi-media piece titled “Lava Sun” on display during her March 2022 exhibit. [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

“The pandemic gave me the push to kickstart the art that I wasn’t really doing before,” Popp said. “I was like, ‘I’m not gonna let this time go by and not upload my art and start selling it.’ I was really motivated.”

For Luckett, her artistic emphasis on embroidery pre-pandemic transitioned to journaling. As a student who entered graduate school during the pandemic, Luckett’s entire first year was spent online.

“When the pandemic first happened, I lost all motivation for creative thinking. My embroidery practice really suffered,” Luckett said. “Journaling really helped me because it was lower stakes. I didn’t feel like I had to conceptualize something from beginning to start. I could just mess around in my sketchbook. So that’s kind of how my creativity bounced back in the heat of COVID.”

Luckett’s embroidery work from 2016, a year after she was first introduced to the practice. [Courtesy of Emilie Luckett]

“My grandmother had taught me when I was about ten years old and after that, I picked up my knitting needles maybe once or twice a year,” said Boiarsky. “[In 2020] I taught myself new techniques and knit a variety of different garments.”

Unlike many university students, Boiarsky notes that she had access to studio space during the pandemic, and so was able to use the space for escape and experimentation.

Boiarsky’s 2022 ceramic series of “mug buddies” on display [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

They “mark which mug is yours and you can hang your tea bag on them!” [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

“I immediately went to work with what was around me,” said Norton. “I could finally see Texas with an outside view for the first time. I could finally see these key issues, like invasive species and massive hunting reserves. I didn’t realize that was not normal. I’m finally saying, ‘Why aren’t we discussing this?’”

Norton’s taxidermy from his 2021 ‘Counter Invasive’ Series [Courtesy of Cody Norton]

For others, the pandemic served as an introduction to artistic exploration.

Alakh Patel, an electrical and computer engineering student, was first introduced to artmaking through group painting sessions during the pandemic.

“I think we were just bored of playing card games,” he said.

Patel has since incorporated the practice of painting into his everyday life and now takes non-major art courses through CU.

[Courtesy of Alakh Patel]

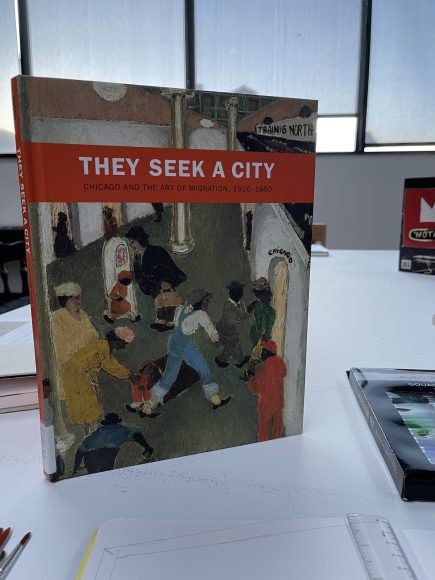

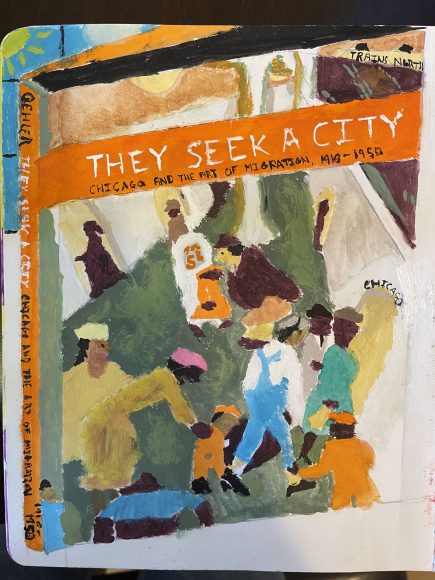

Patel’s reference and painting of Sarah Kelly Oehler’s They Seek A City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910-1950 [Courtesy of Alakh Patel]

The intimacies of self-therapizing through art

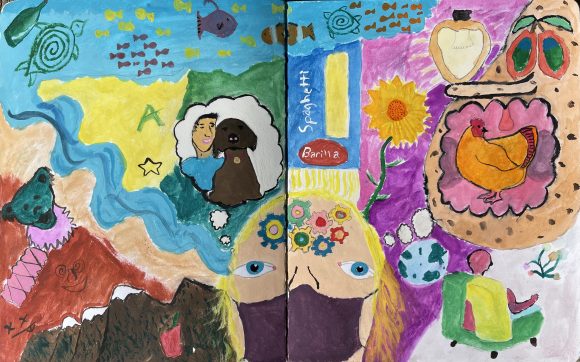

For Popp, art therapy has presented itself explicitly in her work. In her March 2022 exhibit, a centerpiece titled Art Therapy, contained various ceramic sculptures and colored pencil drawings that reflected distinct emotional states. When overcome with sadness, anger, happiness or any distinct emotion, Popp would create. Each individual piece therefore represents a tangible emotion.

“I decided I wanted to use that title because each one of those different shapes to me represents a different emotion,” said Popp. “There was one that was blue with sharper edges. I was frustrated when making it. I pressed really hard with the pencil making that one.”

“Color makes it easier for me to have fun. I’ve been told my art is very whimsical and abstract, and that it has kind of a psychedelic look to it” said Popp of her 2022 piece titled “Art Therapy” [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

“Sometimes if I’m feeling overwhelmed, I draw. I do feel like I’ve honestly done that my whole life, but I don’t think I really realized that’s what I was doing. I think I just was coloring and I would feel like ‘Oh, I’m so much more calm now,’” Popp said.

“Now, I look forward to having that calming time when I know I’m going to color,” she added. “I know it’s going to be able to relax me, just to doodle through anxiety. It takes my mind off of everything. I could literally do it for hours.”

For Emilie Luckett, embroidery works as her therapy.

“One of the biggest reasons I got into embroidery was because it was so meditative. I have anxiety, so I found that when I was doing that practice, it really helped me to slow my mind down and recenter myself,” she said. Luckett taught embroidery workshops pre-pandemic in order to share her practice with others.

Luckett (third from left) teaches embroidery workshop at Recreative Denver in 2019 [Courtesy of Emilie Luckett]

“I am at my happiest when I am creating and making art,” said Boiarsky. “For me, art is a necessity. It can be therapeutic and healing, but it can also be extremely aggravating. Ultimately, it is extremely necessary to my life. I need to have some type of creative outlet to process ideas and feelings and put something out into the world.”

For Norton, his place as an educator at CU plays a large role in his relationship with art as a form of therapy. Norton encourages his students to work through self-healing and explore identity by practicing art.

“I always ask my students ‘How are you going to help yourself do this?’” said Norton. “I try to really instill that with my students, like, ‘Don’t stress yourself over all this work, just have fun with it.’”

In his own work, which addresses misconceptions and environmental ethics of trophy hunting and taxidermy, the process of restoring the animals in a respective way proves therapeutic for Norton. Norton preserves and saves all such animals from what he calls the “never-ending death” cycle of taxidermy.

Norton’s repurposed taxidermy from his 2021 ‘Counter Invasive’ Series [Courtesy of Cody Norton]

Alakh Patel actively seeks out art and the arts community as a form of relaxation. Patel says that just being in the vicinity of the art buildings makes him feel more at peace, as opposed to the “depressing” landscape of the engineering buildings on CU’s campus, where he takes most classes.

“If I just need to take a break, but still need to be productive, I go to art,” said Patel. “It just takes your mind off of everything.”

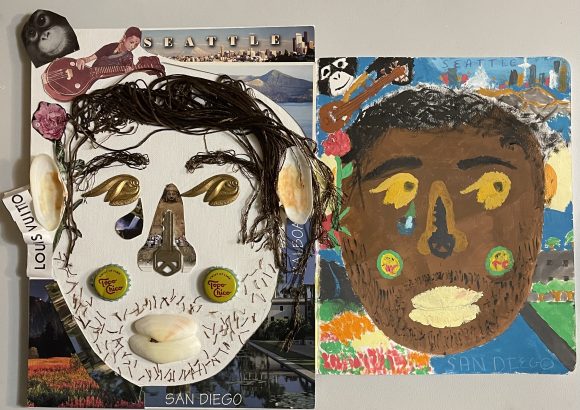

Patel’s self-portrait collage and painting made for his first art class at CU [Courtesy of Alakh Patel]

The art of perfecting and exhibiting existing crafts

Just as the pandemic granted space for newness and experimentation, so did it allow artists the time and isolation to perfect and exhibit their distinctive art styles.

For most, exhibitional and curatorial opportunities were nonexistent during the height of COVID. With restrictions lifted and public spaces reopened, artists have rushed at the opportunity to share their work with the world.

Now a second-year master’s student at CU Boulder, Luckett went straight to work preparing and organizing curated spaces. As an art historian, Luckett’s emphasis lies in social justice and the intersectionality of socially-engaged arts. The pieces Luckett chooses for curated exhibitions highlight the healing properties of community arts.

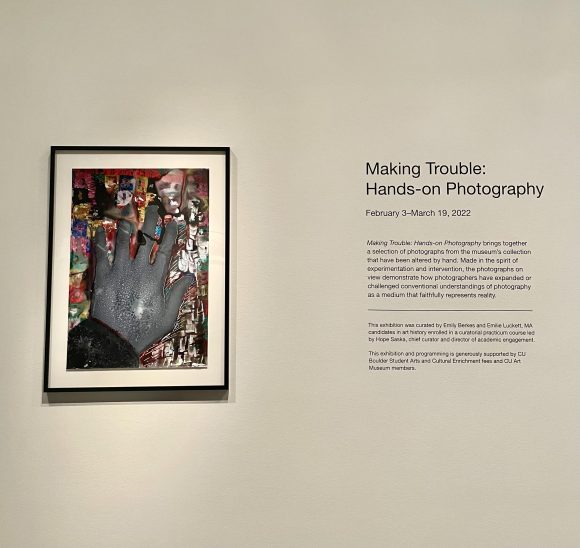

Luckett’s first curatorial exhibit at the CU Art Museum [Courtesy of Emilie Luckett]

Luckett’s first exhibit at the CU Art Museum, titled, “Making Trouble: Hands-on Photography” ran from Feb. 3 to March 19, 2022.

“The sense of community was really wonderful. I feel so fortunate to be in an institution where I can learn these skills in a safe space,” she said.

Popp, now a senior, had her first-ever solo exhibit in March of 2022. The exhibit aimed to express Popp’s identity as a female artist with ADHD. Vibrant pieces of ink, colored pencil and ceramics filled the room. From depictions of dancing bodies to mushroom landscapes, Popp’s exhibit was immersive, colorful and exciting. The exhibit made clear use of the vibrantly colorful artistic mediums adapted by Popp during the pandemic.

Popp poses alongside her work at an individual exhibit during March of 2022. [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

In both February and March of 2022, Boiarsky was also able to present her sculptural work in group exhibitions. Boiarsky’s February exhibit, titled The Little People Running Around in My Head consisted of small-scale ceramic figures. Adorning one of the figures was a knitted scarf– a technique Boiarsky was reintroduced to during the pandemic. The second figure sits with outstretched arms– a severed head in its lap.

“These figures are personifications of my own anxiety. Often during a stressful week, I comment to my friends… ‘I am like a person running around with my head cut off.’ So, it seemed appropriate, even fated, that during a stressful week, the little man in my head had his head fall off,” read Boiarsky’s artist statement about her rather ironic accident.

Boiarsky’s 2022 mixed media series titled “The Little People Running Around in my Head” [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

Boiarsky’s 2022 mixed media series titled “The Little People Running Around in my Head” [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

“I’m trying to save them, basically,” said Norton. “There are ethics involved. If I get a piece that’s decrepit and falling apart, I go and bury it– just to be respectful. I’m trying to use the space to advocate for specimen that are already extinct, or still alive”

Norton’s university office is covered with once-discarded taxidermy that he has taken upon himself to save. The floors, walls and ceilings are adorned with uniquely restored species that each hold a special place in Norton’s heart.

Norton’s office is stuffed with taxidermy, books, and woodworking tools. [Courtesy of Courtney Brown]

“I just wanted to get better, or at least have a class where I could learn more techniques. One thing that I really love is the ability to do finer details. Before, I would have to scale things up and make a big canvas to avoid finer details, but now I’ve got small little brushes to paint all these fine details, which is really cool,” said Patel. “I’ve never been able to do that kind of stuff before– things that make the paintings either more realistic, or more interesting, or prettier. There’s definitely been a lot of improvement.”

Patel’s sketchbook piece titled “Abstract: A Stream of Consciousness” [Courtesy of Alakh Patel]

Today, students and educators like Popp, Luckett, Boiarsky, Norton and Patel maintain a diverse community of university arts that works to uplift and educate. The practice of art as self-therapy is unique to its respective creators. The revival of CU’s arts community has been brought about by the resilience of university students.

From the isolated nature of creation during the pandemic’s start, to the awkwardness of online art courses during its rise, and the now more traditional styles of learning, universities have ridden out each wave of the pandemic with a distinctive sense of determination. The legacy of pandemic-inspired artwork is one of healing, exploration of identity, community and preservation.

“Art is not always easy; it’s not always fun,” said Norton. “But, it can always be therapeutic.”

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Courtney Brown at courtney.brown-1@colorado.edu.