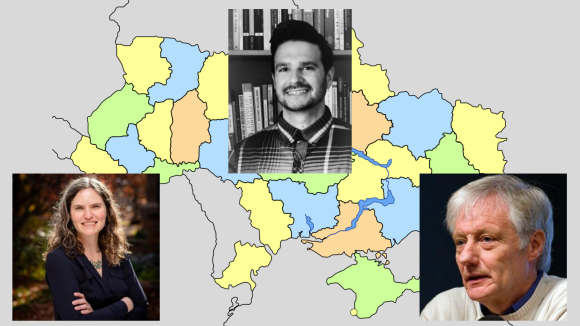

English, Hutchinson and O’Loughlin are all professors at CU Boulder. (Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and the University of Colorado Boulder)

On Feb. 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” in Ukraine. Many world leaders condemned this action as an invasion, as Russian troops attacked the borders and ports of the neighboring country.

At the University of Colorado Boulder, experts on conflict, the region and its history said the consequences of this attack are enormous for the people living through it and the world.

“There’s a lot of potentially far-reaching consequences well beyond just Russia and Ukraine,” University of Colorado Boulder Geography Professor John O’Loughlin said.

According to O’Loughlin, the conflict could escalate if NATO member-states that are close to Ukraine come into contact with Russian soldiers.

Nations that make up the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have agreed on a system of mutual defense, meaning if one NATO country is attacked the rest of the treaty’s member nations are obligated to help.

“The problem is that what starts in Ukraine doesn’t stop in Ukraine, because NATO is next door,” he said. “It means that there’s a risk of NATO troops and of Russians coming in contact with each other.”

History’s impact on modern events

The roots of this invasion go far back into history. Doctor Erin Hutchinson teaches Russian and Eastern European history at CU Boulder. While she said that history is important to understanding the current situation, she also said there are other things to consider.

“I think that the Ukrainian people’s democratic choice should determine what kind of government they have,” she said.

Hutchinson said that, for a historian, the origins of this conflict can be traced back to the 9th century.

Ukraine and Russia, Hutchinson said, were both a part of the same political entity but developed different cultures, languages and societies over centuries, albeit with some similarities.

In the 17th century, Ukraine was brought under the banner of the Russian Empire. During that time, Ukrainians were banned from printing their language in text and many other forms of cultural expression.

After the fall of the Russian Empire, most of modern-day Ukraine was absorbed into the Soviet Union. Under the USSR, Ukrainians had more cultural freedom but were still not given sovereignty. In 1991, after decades of frustrations with the Soviet government, Ukrainian citizens voted in favor of independence.

However, the Russian government had stepped up attempts to delegitimize Ukraine’s sovereignty in recent years.

“What we’ve seen Putin’s government do, especially in the last year, is really return to some of that old imperialist rhetoric,” Hutchinson said.

More than an international crisis

On Feb. 3, several weeks before Russia’s military launched their invasion, O’Loughlin said he feared for civilians caught in the middle of a potential armed conflict between the nations.

Now, as the United States levies sanctions against Russian leaders and reports of bombing in Ukraine flood social media, he says those fears have been realized.

“The images and the pictures of families huddling in the subway stations in Kyiv and Kharkiv and other Ukrainian cities are just heart-rending,” O’Loughlin said.

As a researcher, O’Loughlin has been working in Ukraine since the early 1990s. His research focuses on public opinion polling, some of which is very relevant to the crisis today.

In one survey, O’Loughlin interviewed 4,000 residents of the Donbas region of Ukraine. Ukrainian military forces and Russian-backed separatist groups have been fighting in the region since 2014.

In that survey, he found that a majority of people there agreed with the statement that their nationality was less important than being able to provide for themselves and their families.

“There’s a real mismatch between (this) kind of big geopolitical and military confrontation and what life is like for people on the ground. They don’t care about it but they’re caught up in it,” he said.

O’Loughlin is not alone in his concern for the 44 million people of Ukraine. Professor Michael English, the associate director of CU Boulder’s Peace, Conflict and Security Program, said he is worried the overarching international importance of a war will diminish what those in the country are facing.

“Ukrainian civilians are going to experience the brunt of the effects of the conflict. That shouldn’t be forgotten in all the talk of what this means for the U.S. or what it means for Russia,” English said.

Is more military conflict likely?

Through social media and other public forums, many have expressed their concerns about this conflict escalating to a larger scale. President Joe Biden announced a sweeping set of sanctions that were designed to cripple Russia’s economic systems. English said that kind of action is exactly what he is hoping for.

“Thankfully (the) dominant conversation in the U.S. still seems to be around sanctions and I’m hearing a lot of good talk about making Russia into a kind of international pariah because it’s violated international law,” English said.

English hopes that those in power will resist the drumbeats of escalating the conflict because, he says, a global war will not provide any lasting solutions.

“There’s no kind of path to military victory in a conflict like this,” he said. “There’s got to be some kind of political ending to this and people forget that and assume that this is just about occupying territory.”

While harsh sanctions and anti-war protests in Russia itself have made English hope for a political solution, O’Loughlin said whether or not the conflict escalates is dependent on the result of the fighting in Ukraine.

“My fear is that some people in the U.S. think of this as a way to give Russia a bloody nose, to basically get them bogged down in Ukraine, but that completely ignores the consequences for the Ukrainians who are there and who are caught in the middle,” O’Loughlin said.

While avoiding more fighting is the end goal, the methods for opposing the invasion by other means will be slower, English said.

“The sanctions are their long-term strategy. We’re talking months, not days. And so this conflict, until Putin achieves his objective, could go on for some time,” English said.

That objective is another important component of this issue. English and O’Loughlin both said that taking the time to understand Putin’s reasoning for the invasion is important.

“(Putin) feels like NATO has been encroaching into territory that he thought NATO would never expand into and as such, this is just one attempt to secure Russia’s borders,” English said.

Putin has escalated his rhetoric of veiled threats to Ukraine’s allies in recent days, telling Western nations to stay out of the way.

“He’s clearly trying to make sure that outsiders stay away from this so that he can achieve his aims in Ukraine,” O’Loughlin said. “I’ve never seen the like of it from a Soviet leader, probably back to the early (1960s) around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Helping those in need

While solutions are few and far between, English and O’Loughlin said there are ways to help those in need. The International Red Cross, which helps refugees, is an organization they both recommend.

United Help Ukraine is another organization that provides medicine and humanitarian aid for “those injured in the war in Ukraine.”

For those who are interested in learning more about the history of Ukraine and Russia, Hutchinson recommends reading “The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine” by author Serhii Plokhy and “Ukraine: What Everyone Needs to Know” by Serhy Yekelchyk.

Hutchinson also said people should advocate for action on the invasion if they are concerned.

“I would recommend that people exercise their democratic voice and call their senator’s office and make their voice heard,” she said.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that President Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops to attack Ukraine on Feb. 28. President Putin made this order on Feb. 24.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Henry Larson at henry.larson@colorado.edu.