Boulder Creek (Allie Greenwood/CU Independent)

Levels of the harmful bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli) in Boulder Creek have spiked several times in the past three years, according to reports obtained by the CU Independent.

The bacteria, found in mammal intestines, usually comes into contact with water sources through fecal contamination. While the majority of E. coli infections cause vomiting and diarrhea, in extreme cases, the bacteria can lead to severe anemia and kidney failure. After years of the issue, one Boulder community member is advocating for change

Art Hirsche, a member of the Boulder-based non-profit Boulder Waterkeeper, is calling on who he refers to as the “stakeholders” for greater accountability. It includes the City of Boulder, Boulder County and the University of Colorado Boulder, all entities that own property in which the stream flows.

“I would like to see them be transparent,” Hirsche said. “They have a responsibility.”

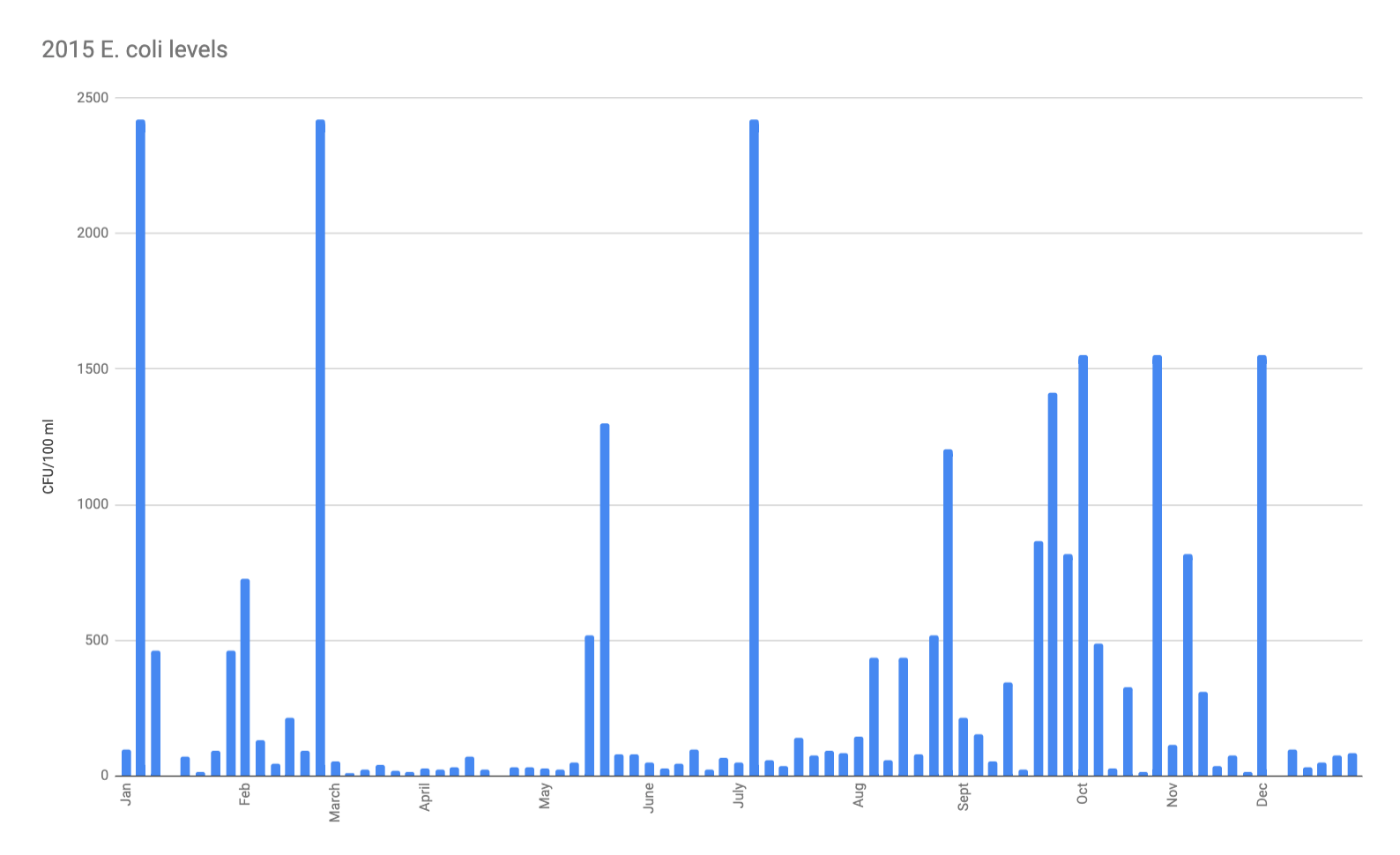

E. coli is measured in colony forming units (cfu) which estimate the number of bacterial cells in a given sample, with a typical water sample size being 100 milliliters. The City of Boulder has conducted roughly 80 sample testings per year between 2015 and 2018. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) states that levels for fresh recreational water, like the creek, should not exceed 126 cfu. Throughout the last three years, some E. coli measurements in the creek were over 2,000 cfu, 15 times the EPA standard.

A “languishing” issue

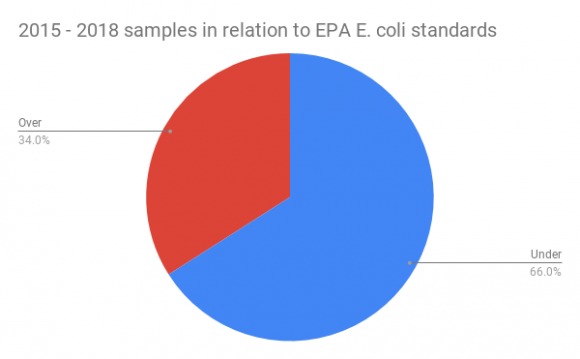

116 of 338 samples between 2015 and 2018 exceeded EPA E. coli standards. (Robert Tann/CU Independent)

Determined “impaired” in a 2004 study by the City of Boulder, the creek has remained a spot for E. coli concentration ever since. It took until 2011, seven years after the findings, for the first total maximum daily load (TMDL) study to be done. In compliance with the U.S. Clean Water Act, TMDL studies identify the maximum amount of a pollutant that a body of water can receive while still meeting water quality standards. In this case, studies were done to measure levels of E. coli in the water.

According to Aimee Konowal, watershed section manager for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), TMDL studies took years to be implemented as the creek was not a “priority” at the time. CDPHE has dealt with a “growing list” of impaired water sources, said Konowal.

“We don’t always have the resources to address all of the impaired waters at any given time,” Konowal said, adding that in 2004 the department had other obligations when it came to tackling water issues.

While TMDL studies stopped prior to 2015, a plan was funded by the Keep it Clean Partnership (KICP) to further monitor and collect data along the creek, leading to regular monitoring over the next three years. While the majority of samples show E. coli levels being under the 126 cfu maximum, exceeding levels are frequent. Of the 338 samples taken between 2015 and 2018, over a third exceeded EPA E. coli standards.

To Hirsche, these studies show a “languishing” issue, one that is in desperate need of action.

“What concerns me most is how [residents] don’t understand that there is a water quality standard being exceeded,” Hirsch said. “If they know and they’re willing to accept the risk, that’s one thing. But the fact is, the stakeholders have failed to adequately inform the local public about what the risks are.”

Children and the elderly are among the more vulnerable demographics when it comes to the health effects that E. coli can cause. Children under five years old run a higher risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome which destroys red blood cells and causes kidney failure. About 2-7% of E. coli infections lead to this. As summer nears, Hirsche worries that increased recreational activity in the creek could spell disaster.

2015 E. coli levels exceeded the EPA standard 29 times.

2015 E. coli levels in Boulder Creek. (Robert Tann/CU Independent)

Candace Owen, stormwater quality supervisor for the City of Boulder, assures that an implementation plan by the city is nearly finished. Owen mentioned locating specific outfalls of waste and furthering investigations into such areas as a way to help mitigate E. coli levels.

Owen said timeline estimations for how long the plan will take to generate results are unclear at this time, although she guesses each sewer outfall could take up to two to three years to fully control. Owen hopes the plan will be ready for implementation next month but says that recent discussions could delay it as the city continues to look for more feedback.

When asked about the high amounts of E. coli in some samples, Owen said that E. coli measurements fluctuate regularly and that it is a “challenging” process. She said that one data sample is not enough “to tell a story.”

Hirsche disagrees, citing that it is not just one sample but many that have exceeded limits and that is is “no anomaly.”

“Flexibility” when it comes to initiatives

Among Hirsche’s many concerns is a perceived lack of communication between the city and entities like CDPHE and CU Boulder. To him, CDPHE has shown a “hands-off approach” for dealing with the creek.

“[CDPHE] is asleep at the wheel,” Hirsche said.

MaryAnn Nason, communications and special projects unit manager for CDPHE, said that the department “wants to collaborate” with entities like the City of Boulder but stated that there are “boundaries.” Nason said that data on the creek cannot be requested to a “specific degree.”

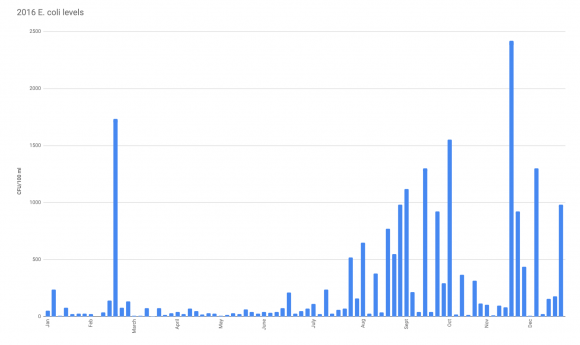

2016 E. coli levels exceeded the EPA standard 28 times.

2016 E. coli levels in Boulder Creek. (Robert Tann/CU Independent)

In regards to the development of TMDL studies and why the first took so long, Nason said that studies are a result of collaboration between CDPHE and other stakeholders. However, according to Owen, the City of Boulder conducted its first TMDL study on its own as it knew that CDPHE would not be able to address the issue of the creek at the time.

As Nason explained, CDPHE can set boundaries for municipalities like the city when it comes to water standards but wants to allow “flexibility” for the city to address the issue how they see fit.

Certain initiatives are outside CDPHE’s control, such as signposting around the creek, which Hirsche believes would help better inform the public. CDPHE’s Amy Konowal said the decision is not typical but has been done in the past in order to warn the public, such as when Denver County posted signs around Confluence Park due to the results of a TMDL study. Nason said that while the department may not require the City of Boulder to post a sign, they would encourage it.

According to Owen, conversations regarding signposting are “on the table,” but she also believes that the city does not yet have a “precedent” that would justify posting signs. As of now, the City of Boulder has no immediate plans to signpost.

“The city takes this very seriously,” Owen assured. “[The city] is very receptive to feedback from the public and understands that the public has concern.”

Hirsche is skeptical of the city’s reluctance to post signage, believing that it may reflect poorly on Boulder’s reputation as a clean and healthy environment.

“[The city] does not want to advertise it,” Hirsche said.

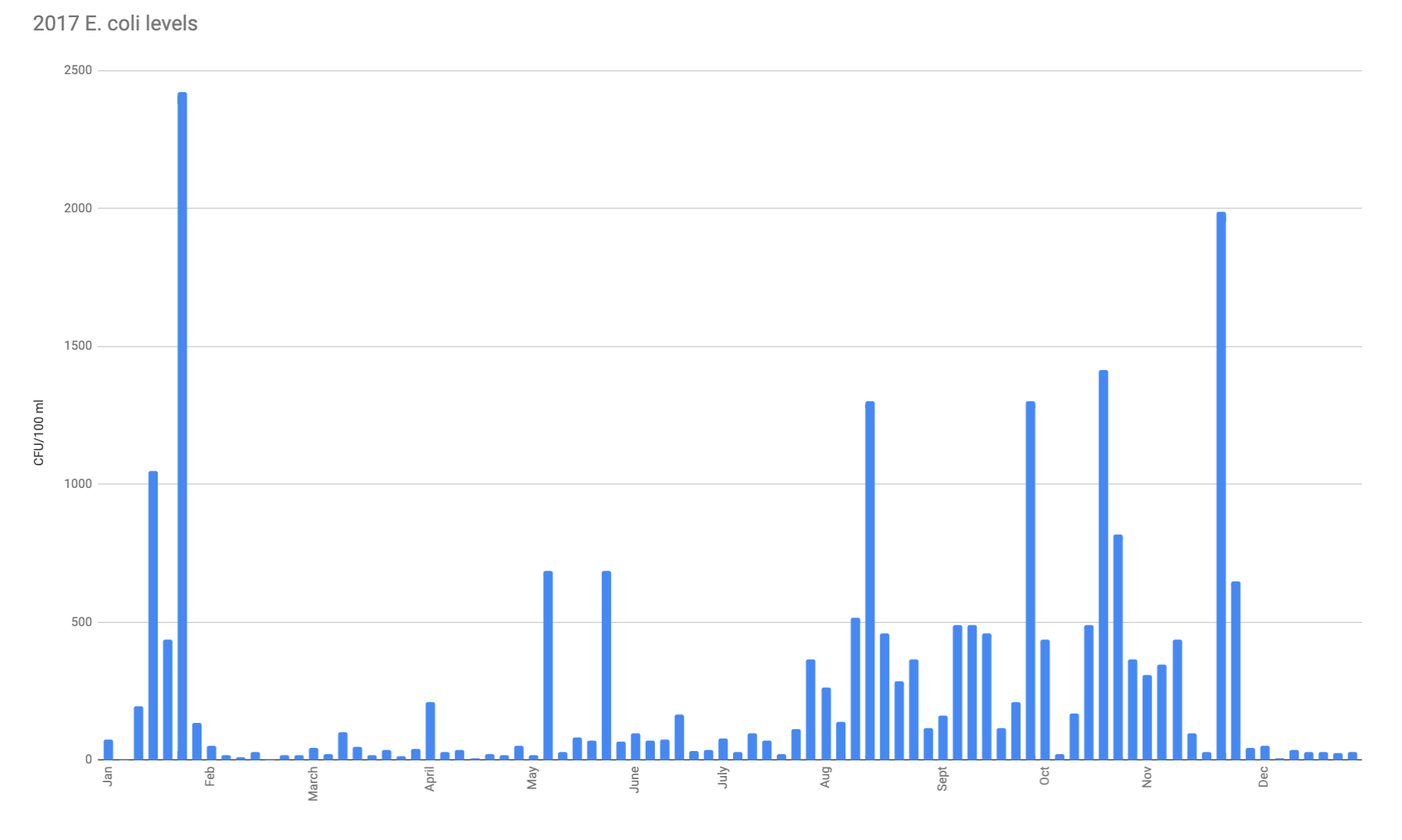

2017 E. coli levels exceeded the EPA standard 34 times.

2017 E. coli levels in Boulder Creek. (Robert Tann/CU Independent)

“If I’m wrong, prove me wrong”

Aside from CDPHE and the city, Hirsche has also called on action from CU, but conversations have been mixed. Hirsche says finding reports from the university’s own studies have been difficult. He has requested an E. coli meeting with representatives but has yet to hear back.

Joshua Lindstein, CU facilities communications and outreach specialist, told the CUI in an email that the university has been collaborating with the city since “at least 2008.” Lindstein cited an initiative years ago in which both the city and CU contributed resources to block off and clean out a storm line on East Campus.

He wrote that the university has invested “significant effort” to mitigate E. coli entering the creek via campus storm drains. In the instance that leakage is found, CU “promptly” makes repairs, with Lindstein calling leaks a “rare” occurrence, having only happened twice in the last five years.

Further projects include increasing sampling and investigation activities related to identifying E. coli sources, as well as revisiting CU’s animal access projects to limit wildlife impacts on storm lines, according to Lindstein.

Hirsche understands that some initiatives have been taken, but it seems more like “little bits of projects” rather than a comprehensive implementation plan.

“If I’m wrong, prove me wrong,” Hirsch said. “I do not believe that [CU] has gone through the full gamut of investigation.”

According to CU, raccoons on campus may be a major contributor to fecal excretion responsible for E. coli contamination. Lindstein wrote that “significant efforts” have been made in recent years to “curtail wildlife access to storm lines.”

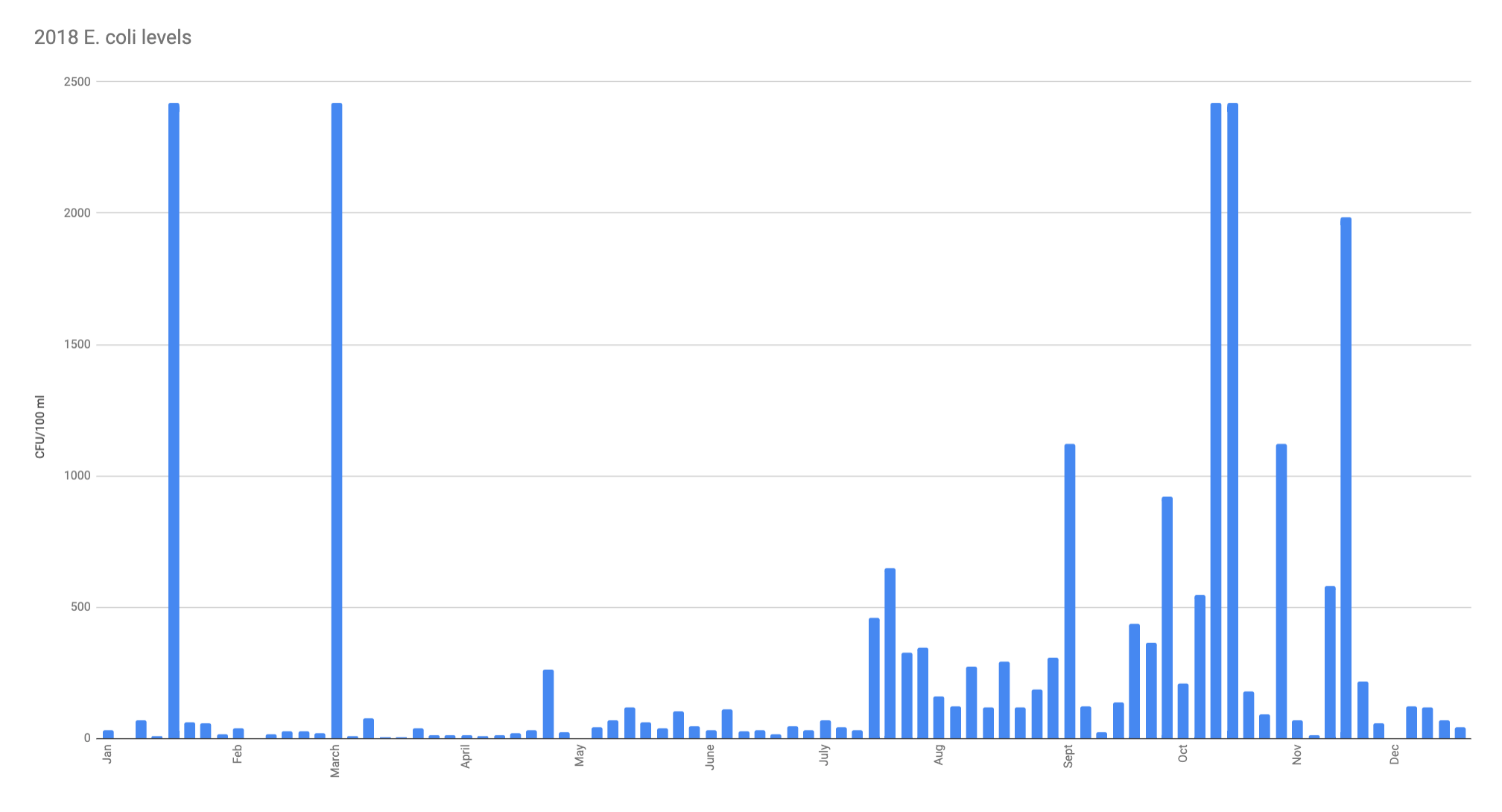

2018 E. coli levels exceeded the EPA standard 26 times.

2018 E. coli levels in Boulder Creek. (Robert Tann/CU Independent)

Like the city, CU has not posted any signage about E. coli levels. Lindstein said that CU maintains signage at storm drain inlets on campus property to warn against illicit discharges or dumping of materials. However, Lindstein said that E. coli signage along the creek is outside the university’s jurisdiction and would have to go through the city, county or state.

Hirsche, on the other hand, believes that CU is “just as much of a stakeholder as the city.”

The water quality advocate said he is not “pointing fingers at anyone” but knows “we can do better.” He is disappointed that the conversation still needs to happen in order to fix such a longstanding issue.

“Everyone waits to the last minute when there’s a problem,” Hirsch said. “Nobody does anything ahead of time.”

Time ticks on as Hirsche and the Boulder Waterkeeper await the city’s implementation plan. Until then, Hirsche continues to push for more awareness of the issue as Boulder Creek remains a “broken stream.”

Contact CU Independent Senior News Editor Robert Tann at robert.tann@colorado.edu