Engineering Center (Fiona Matson/CU Independent)

Attempts are being made within the University of Colorado Boulder’s College of Engineering and Applied Science to remedy a lack of gender parity.

CU’s engineering school wants to become the first public college in the U.S. to have an equal number of female and male engineering students. Currently, the engineering school as a whole is about 28% female, with ratios varying between majors and a higher percentage of women in the younger grades.

CU is already well ahead of the national average. According to data from the Society of Women Engineers, only about 20% of people holding bachelor’s degrees in engineering or computer science are women. Women are also more likely to leave STEM programs while they are undergraduates, with one study finding that 30% leave a STEM major for a non-STEM major and 14% do not receive a degree.

In 2017, the school hired a new dean, Robert Braun, who is ambitious about improving the college climate.

When asked what the timeline for achieving gender parity at CU was, Braun said “Yesterday.”

Braun became dean of the engineering school in January 2017 after having worked at NASA and Georgia Tech. He helped develop the college’s strategic vision, which has four main goals of improving the college. Among them is “being the first public engineering college with a 50 percent women undergraduate population while reflecting the demographics of [Colorado’s] high school graduates.”

Female students currently make up 27.9% of the engineering school. Undergraduates are 28.1% women, and doctoral candidates are 29.4% women.

Braun said he hopes that incoming freshman classes will soon be half female, and from there they simply need to continue the trend to maintain an even ratio.

According to university data, the engineering school’s freshman class of Fall 2018 was 40% female. Beth Myers, director of analytics for the college, said that 45% of those admitted for next fall are women.

“We expect the class to be somewhere between 40-50% women depending on the proportion of women that accept our admission offers,” Myers wrote in an email.

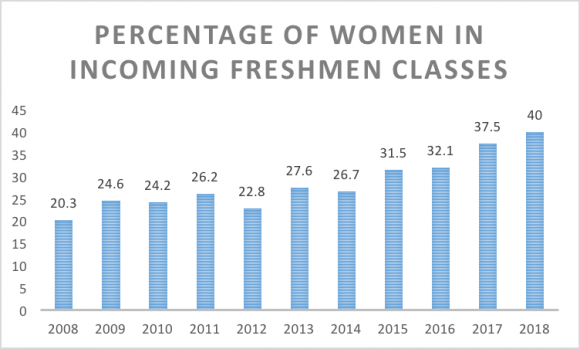

According to Braun, the engineering college has been increasing the amount of female students by a rate of about 2% per year, but after making gender parity a clear goal, improvement has been faster. He said that in 2016-2017 the incoming freshman class was 32% female, and after they announced their goal, the next year’s class jumped to 37%. In just 10 years the school has doubled the percentage of women in incoming classes from 20.3% in 2008 to 40% in 2018.

The percentage of women over time in the college of engineering’s incoming classes. (Carina Julig/CU Independent)

“Just having this conversation in the college, shining a light on this issue, has really improved our recruiting of women engineers and underrepresented minorities,” Braun said.

While CU is above the average, the actual numbers vary greatly between majors.

According to Fall 2018 enrollment statistics from CU’s Data Analytics department, the most equitable engineering majors are environmental engineering, chemical and biological engineering, and technology, arts and media, which had freshman enrollment rates of 59.6%, 52.8% and 45.5% women, respectively. The least equitable majors are engineering physics (14.5%), mechanical engineering (19.6%), electrical engineering (20.2%) and aerospace engineering (21%). Computer science, one of the most popular majors of 2018, only had a 23% female freshman class that year.

CU has several student groups for women in STEM majors, including a Society of Women Engineers (SWE) chapter and Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE). Former SWE president Katie McQuie said that the school has been proactive in trying to improve the climate for female engineering students, but issues still persist.

According to McQuie, sexism is less overt and usually more under-the-radar, saying some are picked less to work in groups by people who say “oh, you’re a girl — you probably don’t know what you’re doing.” Former Vice President Vanika Hans agreed, saying that she had to explain her ideas more than her male peers in order to be taken seriously, which was frustrating.

Stereotypes about women in engineering can also make it more difficult for them to succeed in the field.

“It seems like a lot more women take failure to heart and then switch majors as a result,” Hans said.

She believes the preconception that women are not going to be good at engineering and math is harmful to them as it instills doubt within themselves, leading them to struggle even more in classes.

To counter these issues, SWE does outreach to local K-12 schools to show young girls that they can pursue engineering, and they host career development events allowing them to meet with women working in the industry. One of the group’s main goals is to provide a community for women in the engineering college so that they have a sense of belonging.

Hans said she believes that CU is attempting to make a change but that students are not always responsive to it.

“It has to be a cultural change for sure,” Katie McQuie said.

She remembered a time when her department had a meeting to address a report that female students in chemical engineering didn’t feel welcome. While she appreciated the meeting, it didn’t translate down to her day-to-day experience in the college.

“The department is trying to fix things, but a day after the meeting I experienced sexism,” she said.

The college maintains the BOLD Center for supporting students who are underrepresented in engineering, which includes female students, students of color, LGBT students and first-generation students. Multiple student groups operate out of the center, including SWE and the National Society of Black Engineers.

Sarah Miller, director of the BOLD Center, said that CU is unique for this approach and is considered a leader in promoting diversity in engineering.

“In a traditional engineering college there’s a women in engineering program and a minorities in engineering program,” Miller said.

The BOLD Center provides a more holistic approach to diversity, providing support to all students who are traditionally underrepresented in the field. Along with hosting student groups, they also offer tutoring and hold social and career-oriented events while doing outreach to local high schools and community colleges.

Lilian Garcia, from the #ILookLikeAnEngineer campaign. (University of Colorado)

The school also launched the “I look like an engineer” campaign to counter stereotypes about gender barriers in the engineering field. Originally started by a female engineer in San Francisco, the campaign went viral and is being promoted at CU to highlight the diversity of the school’s engineering program.

“There are so many stigmas surrounding programmers … that are just outdated and untrue” computer science senior Jenny Michael wrote in her profile. “In my personal experience, the software development environment loves diversity, both in terms of people and ideas.”

“I don’t fit the norm of what an engineer is,” environmental engineering graduate Lilian Garcia wrote. “First, I am a woman. Secondly, I am Latina. I want other Latinas to look at my photo and see me as a role model.”

The engineering school has been one of CU’s most proactive colleges in promoting diversity with the “I Look Like an Engineer campaign” outreach to high schools and community colleges and numerous programs through the BOLD Center. But achieving gender parity is still something that will take time.

“That is the long-term goal for the college, but it’s not a goal that I have total control over,” Braun said.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Carina Julig at carina.julig@colorado.edu.