CU GLBTQ buttons at the UMC. (Robert R. Denton/CU Independent File)

Opinions do not necessarily represent CUIndependent.com or any of its sponsors.

The Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, GLAAD, is hosting this year’s Bisexual Awareness Week, or #BiWeek, from Sept. 23 to Sept. 30. Despite their lack of media representation, you’d have to be trying pretty hard to be unaware of bisexuality.

A poll conducted last June by Buzzfeed and Whitman Insight Strategies found that a whopping 46 percent of LGBTQ Americans aged 18-29 who participated in the survey identified as bisexual, compared to only 9 percent of those aged 60 and older. In other words, the percentage of LGBTQ Americans who identify as bisexual increased from almost one-tenth to almost half the LGBTQ population in just three short decades.

It should be noted that only 880 people participated in the Buzzfeed and Whitman Insight Strategies survey, which is not necessarily representative of the more than 10 million self-identified LGBTQ Americans as of 2016.

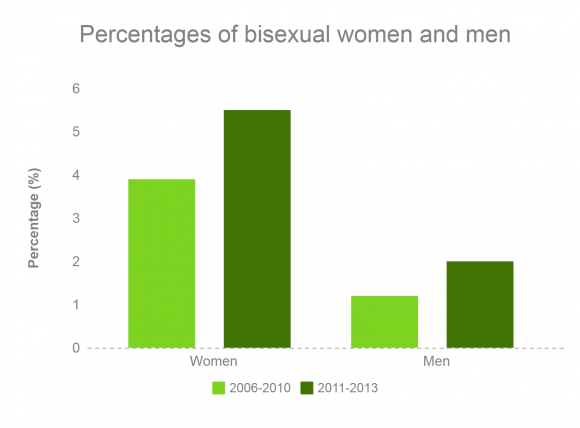

In early 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that from 2011 to 2013 “higher numbers of both women and men identified as bisexual, 5.5 percent of women and 2 percent of men, compared with 3.9 percent and 1.2 percent respectively [in 2006-2010].”

Researchers collected data from over 9,000 participants aged 18-44.

In a similar study conducted by CU Boulder in the fall of 2015, 12,717 students participated in a sexual misconduct survey and answered questions regarding their sexual orientation. Bisexuals constituted the second most common sexual orientation among CU Boulder students. The most common identity was heterosexual, with 10,912 students, while 629 students identified as bisexual, 196 identified as gay, 84 identified as lesbian and 207 identified as asexual.

Percentages shown above are slightly different from those displayed in the survey, as options “not included in list” and “prefer not to answer” were excluded from the chart.

This brings about my first “queery” — why are there so many bisexuals?

Allow me to begin with a clarification. While sexual orientation is not a choice, the identifiers that people use to define their sexuality, to a degree, are.

The rise in the self-identification of bisexuality is most likely not the result of a rise in attraction to more than one gender, but a change in how people recognize and identify their attraction. Many of us exist on the borders between various sexualities and genders and choose for ourselves what describes us best.

Possibility #1: Sexual fluidity is more encouraged in the United States today than before.

CNN’s aforementioned report on people aged 19-44 stated that “among those who labeled themselves as heterosexual, 12.6 percent of women and 2.8 percent of men experienced sexual contact with the same sex.” People opening themselves up to such experimentation potentially allows for more “bisexual awakenings” and the increasing normalization of bisexuality.

“It’s a new generation of people being a lot more comfortable with experimentation and self-discovery,” said Katie Burkholder, freshman art and English major.

Possibility #2: Pansexuality and polysexuality may be more accurate terms for some people, but are less known than bisexuality.

Bisexuality, given its longer history, is an easier word for many people to swallow than more recent identifiers such as pansexual or polysexual.

Pansexuality is defined as the attraction to a person regardless of their sexual orientation. Some argue that pansexuality is more inclusive than bisexuality, which people often define as an attraction to men and women and doesn’t appear to leave room for other non-binary identities. Polysexuality is defined as an attraction to several, but not all, genders.

“As of right now I identify as a bisexual woman mostly because it’s what I feel most comfortable with and have the most knowledge of,” said freshman dance major Sarah Napier. “Our society uses the word bisexual more than polysexual, and people understand my sexuality more when I use bisexual.”

“People are more educated about bisexuality,” Napier said. “And unfortunately, our society often uses binaries to describe gender, which makes bisexuality more common.”

Possibility #3: Compulsory heterosexuality exists.

Compulsory heterosexuality, a term coined by Adrienne Rich, a prominent poet and essayist, is the phenomenon that lesbians experience when they convince themselves of heterosexual attraction under the weight of heteronormative societal pressures.

Gay women often feel pressure to feel attraction to men, which may result in a “false diagnosis” of heterosexuality or bisexuality. An important clarification: just because some people misidentify themselves as bisexual does not mean that all bisexuals are going through a phase.

Drew Johnson, a freshman political science major, now identifies as gay but used to think that they were bisexual, “which is likely due to that compulsory heterosexuality and/or repressed feelings.”

“Pretty much all of middle school and my first two years of high school was me trying to convince myself that I wasn’t gay, which involved me dating-slash-hooking up with boys,” Johnson said.

I can relate to Johnson’s experience. I considered myself bisexual for upwards of five years before coming out as a lesbian at the age of 17. Liking women was one thing — not liking men was another thing entirely.

If I was bi, my family could still fantasize about scaring off boyfriends and tormenting husbands. As my parents’ only daughter, there was something inside of me that wanted to fulfill the role of a boy-crazy teenage girl who would eventually get handed off to a man who would protect me from the world. Bisexuality, for me, was a way to hold onto the possibility of starting a family that my relatives would be proud of.

That is, until it became evident that my parents couldn’t care less who I ended up with, and I soon thereafter dropped the “men are attractive” act.

So, will bisexuality eventually take over? Maybe not.

Pansexual, polysexual, queer and similar sexual orientations may eventually beat out bisexuality. As previously mentioned, bisexuality — most likely because of its prefix bi — is often perceived as an attraction to two genders: men and women. This definition, though often debated, leaves no room for individuals who are nonbinary, genderqueer or otherwise do not fall under the categories of “man” or “woman.”

If there’s one thing for sure, it’s that the move towards sexual fluidity has thus far been a rapid one. Perhaps there will come a time when we are not identified simply by our attraction to genders, but to people.

Not as long as I’m around, though. Boys are yucky.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Anna Haynes at Anna.Haynes@colorado.edu.