Inside the Gender and Sexuality Center. (Fiona Matson/CU Independent file)

LGBT graduate students at the University of Colorado Boulder are twice as likely to leave the university without completing a degree than their heterosexual peers, according to a 2014 survey from CU Boulder.

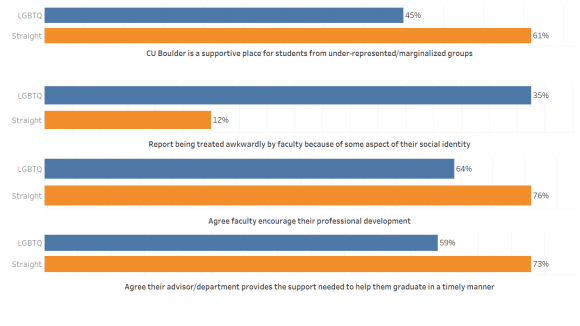

The Graduate Student Social Climate Survey was conducted in 2014, but the full results were not released until Oct. 2017. The survey found that LGBT students in master’s and doctoral programs reported a substantially less positive social climate than their peers. Fifty three percent of LGBT master’s students reported feeling welcome at CU compared to 75 percent of straight students. Fewer than half agreed that CU Boulder is a supportive place for marginalized students.

(The survey uses the term “GLBQ+” to refer to gay, lesbian, bisexual, and queer students as they did not collect enough respondents that identified as transgender to analyze. Other sources used for this piece used the term LGBT to include transgender people.)

(Chris Koehler/CU Independent)

LGBT students also reported much higher incidences of witnessing discriminatory comments, ‘awkward treatment’ by faculty because of their identity and experiencing more hostile treatment than straight students. Lower proportions of LGBT graduate students compared to the overall grad student population believe that faculty encourages their professional development and that they are receiving the support needed to graduate on time.

(Chris Koehler/CU Independent)

Additionally, LGBT graduate students were twice as likely as straight students to drop out of the university before completing their degree. This was the only disparity in retention, there were no statistically significant differences between genders or racial groups.

These findings were largely unknown before the survey’s release. Scarlet Bowen, director of CU’s Gender and Sexuality Center (GSC), said her office had heard complaints from individual graduate students, but that they had not been aware of the scope of the problem.

“This is not a testament to our inclusive campus at all,” Bowen said.

Bowen also said part of the issue is graduate students’ fears about being seen as difficult and not wanting to risk jeopardizing their futures in academia. Grad students are in a precarious place in the university system, as they have little institutional power and their academic futures are largely in the hands of their advisors. She said many are reluctant to raise complaints about discrimination for fear of being seen as difficult to work with.

“You have to be really careful about how many waves you make as a graduate student,” said Nate Abraham, engineering student and board member at CU’s United Government of Graduate Students (UGGS).

The GSC has a number of programs for graduate students, but student involvement remains low. The center runs a Facebook group for LGBT graduate students and partnered with the graduate school to host an LGBT networking night during the fall semester. Additionally, they teach a voluntary workshop at the beginning of the school year for TAs—many of whom are graduate students—on how to foster an inclusive classroom.

Bowen said it can be difficult to get graduate students to attend meetings and programs because of how busy they already are and because many of them have irregular hours. She also said there is no way for the GSC to directly contact students when they are first admitted to CU, which means they are less likely to hear about the center’s resources.

The university is in the early stages of developing a voluntary questionnaire about sexual orientation to university application. The university does not currently collect data about students’ sexual orientation.

Inside the Gender and Sexuality Center. (Fiona Matson/CU Independent file)

Culture varies from department to department

LGBT graduate students that the CUI spoke with described a broad range of experiences in their programs. Whether a degree program was welcoming of LGBT students or not seemed to largely hinge on the individual department’s commitment to promoting an inclusive environment.

Brianna Dym, a doctoral candidate in CMCI’s Information Science department, said she felt very welcome in her department. She said her professor Jed Brubaker, an out gay man, made an effort to connect with LGBT students and make them feel included. He even has a cohort of LGBT students in the department that jokingly refers to themselves as the “Queer Mafia.”

However, an LGBT student in another CMCI department reported experiencing significant challenges within their department and hostility from professors and peers. They asked not to be named out of fear for repercussions to their academic trajectory.

Hollie Allen, a former doctoral candidate in the Spanish and Portuguese department, said she experienced significant pushback whenever she tried to introduce LGBT topics in the undergraduate Spanish classes she helped teach as an instructor. She described the culture of her department as being very patriarchal, and said that one of her advisors thought her relationship with her spouse was “a joke.”

Allen and other students advocated for adding a question about a same-sex family to a test in the family unit of the course.

“On multiple occasions, the question would be submitted and approved, but then on the actual exam it had been changed into a heterosexual relationship,” Allen said. When she asked why the question was removed, faculty told her that the question might be “too hard” for beginner language students.

Allen, along with a number of other LGBT students and allies, also requested that a revision in an undergraduate textbook include vocabulary about LGBT people and non-traditional families. She said when they spoke to faculty about their suggestion it was received positively, but when the revision was published there was no information about LGBT topics.

Allen’s questions about why LGBT material was not being included despite initial support were brushed off, she said.

Allen also said that she and her spouse experienced homophobia while living in married student housing, causing significant stress. She said that while most of the administrators were very welcoming, one of the RAs assigned to their section treated them differently than the rest of the couples. Allen said the initial inspection of their apartment turned hostile when the RA realized they were a same-sex couple and not two female friends.

“Everything was fine when she was first walking through the apartment…but when she saw the sleeping arrangements it was like a lightbulb switched on,” Allen said.

She said the RA would attempt to discipline them for things she did not criticize other couples for, and that she initially tried to write them up for having “too many books.”

“This person had a very particular problem and had been hired multiple times [by the university] even though we reported that she made us uncomfortable,” Allen said. Allen and her spouse could not afford to live in housing that was not subsidized by the university. She said that in the 3 1/2 years they lived in married student housing, they were the only LGBT couple they knew of.

Eventually, Allen decided to leave the university without completing her degree, citing her problems with the university and other issues in Boulder at large as the reasons for leaving.

The anonymous CMCI student mentioned above reported that their work is consistently overlooked in favor of their straight peers’. The student does work focused on LGBT issues and said no professors in their department are specifically knowledgeable about LGBT topics, making it difficult for them to receive the same level of support for their work as other students.

The student said that they are one of the only openly LGBT students in their department and are often passed over for good teaching assignments in favor of straight students. For instance, they described being assigned to TA the department’s introductory course where students who had close relationships with professors were given research assignments.

When they raised concerns, they were brushed off as not being significant enough issues. They said that to make a change, the department should hire LGBT professors and professors that are knowledgeable about LGBT issues, and to stop treating students who make complaints as problems.

“‘Problem students’ are often students dealing with problems,” they said.

Joshua Shelton, a graduate student in the religious studies department, raised the same issue of lack of expertise concerning LGBT issues. Shelton said that while the department is very open and has a number of out faculty and students, none of the professors teach about LGBT issues in religion, meaning he has to go to sociology or women’s and gender studies if he wants to learn about those topics. He said there is little crossover between departments and that the cultures and accepted classroom behaviors are markedly different in different departments, which can be challenging for students navigating academia.

Many students pointed to the siloed nature of graduate student life as being part of the problem. Unlike undergraduates, grad students spend almost the entirety of their time in one department. Department culture and norms have a large effect on whether their experience at CU is positive or negative.

Juan García Oyervides, doctoral candidate and president of UGGS, said while undergraduate students have a lot of institutional support when they arrive at college, graduates are “100 percent dependent on what their departments have available to them.”

At a roundtable for LGBT grad students during the Diversity and Inclusion Summit in February, multiple students shared the issue of feeling like campus resources, such as Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS) and Career Services, are not equipped to serve grad students. This issue is compounded for grad students who have specific needs, such as LGBT students or students of color.

Grad student Jasmine Suryawan shared at the roundtable that there are no resources specifically for LGBT graduate students of color. While she said she appreciated the Queer and Trans People of Color group run through the GSC, she said it is mostly undergraduates and she wished there was something on campus more applicable to her needs.

“[Campus resources] need to specify that they are for grad students because otherwise, grad students will assume that it’s not for them,” said UGGS officer Hillary Steinberg. “And usually, it won’t be.”

Students also brought up the fact that Boulder at large doesn’t have a lot of institutional resources for LGBT people. There are no gay bars in the city, and most large LGBT events and institutions are based in Denver.

“Boulder seems like it’s really queer-friendly, but it can actually be a hard place to be a queer person in,” Steinberg said.

Inside the Gender and Sexuality Center. (Fiona Matson/CU Independent file)

Change is slow, but in progress

Since the survey results were released, Bowen said that the graduate school has been proactive in addressing the disparities for LGBT students. The dean of the graduate school, Ann Schmiesing, met with many different departments in the graduate school along with the Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on Gender and Sexuality, according to a statement from her office. A focus group has not yet been conducted, but Bowen said it is something she wants to do this semester.

The GSC will give a presentation at GradTalks, a social event series the graduate school launched this semester that will feature different speakers. Schmeising said they will enhance the New Graduate Student Welcome events this August to ensure that incoming LGBT graduate students are aware of the resources available to them.

Schmeising said the graduate student peer mentoring program is another program that is available for graduate students. The program partners new graduate students with more experienced mentors and students can request to be placed with an LGBT mentor. She also said she encouraged LGBT students to reach out to her personally with any “thoughts, concerns or questions.”

Officers at UGGS spoke highly of Schmeising, saying she was instrumental in getting the full survey data results released and implementing programs to help LGBT grad students.

However, they raised concerns about whether there was buy-in at the department level for retaining and supporting LGBT grad students. They also raised concerns about lack of knowledge about the underlying causes of the problems facing LGBT grads.

“No one can put their finger on what the problem is,” said Gregor Robinson, doctoral candidate and board member of the CU Boulder Committee on Rights and Compensation. “There is a problem and the numbers show it, but where? What?”

Another graduate student survey pertaining to discrimination and harassment will be conducted in 2019.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Carina Julig at carina.julig@colorado.edu.

1 comment

[…] LGBT grad students struggle with isolation […]

Comments are closed.