Recently, I was immersed in the shoes of PC Malone, a trailblazing female private eye faced with untangling the gritty and violent gang underworld while enduring the challenges of life in 1920’s prohibition San Francisco. A Case of Distrust (2018), the film-noir inspired narrative mystery game is the first title from the newly established game developer TheWanderingBen. I was able to sit down with its founder, Ben Wander to discuss his inspiration and motivation behind their debut game.

CUI: What was your inspiration for the setting in the story, in the classic mystery noir backdrop?

Wander: In terms of it being a mystery, I’ve always, ALWAYS loved mysteries, whether as a novel or film and there just aren’t that many mysteries in video games, you know? I grew up with Agatha Christie mysteries, or you know, watching Sherlock Holmes, things like that. And I never got quite the same experiences in games. There are some, but it’s definitely an underrepresented genre for how often you see it in other media. So it felt like, well, if I’m going to make my own game, why don’t I make it a mystery? It’s already underrepresented and it’s something I really love and am passionate about.

In a similar way, I guess the 1920’s fit that same mold of it was an era I’d already learned a lot about. I got into the 1920’s when Boardwalk Empire first came out. And I was so fascinated by that world that I started doing my own research into it, I started reading books about it, I took an online course and I just became fascinated about the grey areas in that time period.

There are all these illegal, rum-running gangsters, who really aren’t that bad when you think about it from the perspective of, “I just wanna get a drink, and we’re not allowed to do that.” There are all these really interesting characters and situations that you can place people in, in the 1920’s, which also was a time of incredible technological innovation, a really, really good, uh, an economic boom.

And so it just ended up being this perfect mish-mash of “wow, there’s all these new social norms, all this new music, all these new technologies like the automobile,” and at the same time there’s this grey area that makes the characterization of it interesting. So I thought that world was neat and underrepresented, and I thought the genre of mysteries was underrepresented, so when I left to make my own thing it just seemed like the perfect fit.

You say on your website that you wanted to create narrative adventures and settings less explored by large studios, focusing on individuals rather than world-saving. How does A Case of Distrust reflect this design philosophy?

Wander: Sure, yeah, I think anybody in A Case of Distrust — any character in A Case of Distrust — isn’t the hero character. Nobody is perfect, everybody is a little bit of a shade of grey and most importantly, whether they succeed in their goals or not, the world doesn’t change.

I’ve kind of said this a couple times, but if my games succeed, like, let’s say A Case of Distrust succeeds and does gangbusters, does really well, sells a million copies. Or, if it fails, if it sells zero more copies, it just doesn’t do well at all, it’s not going to change who the president is. It’s not going to change the space race, it’s not going to make the aliens who come into town change whether they want to annihilate the planet. So, it’s very important to me, it’s very important to the people around me, but it really doesn’t affect humanity in any way shape or form.

And I think that a lot of these video game stories end up being these really broad epics where they try to tell the pivotal role of some hero that changed society or that even changed humanity in a really profound way, and that’s not a story that I can relate to. So I think that I enjoy the hero story, I like that fantasy, I like putting myself in those shoes, but at the end of the day, I think I relate more to characters who are more grounded and more real and who have their own goals that aren’t necessarily inspired by world saving. Just about where they want to go where they want to be, and their intrinsic motivations that happen because of their past and their history.

The game plays into many classic noir storytelling tropes, however, you encounter many characters who are subject to prejudice characteristic of the time, but uncharacteristic of the genre. What was your motivation to explore the darker side of the time period?

Wander: I don’t even think it’s a darker side of the time period, I think it’s just a more realistic depiction of the time period. You’re right, if you read any hard-boiled novels of the era, something like Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler I mean, those novels are amazing but they very much ignore the social issues of the time. Now, granted, they’re pulpy action thriller novels, detective novels, whatever you want to call them, they weren’t looking to do that and I’m sure it was a lot harder to be able to do that at that time.

I’m not trying to blame the authors for not doing that but, in researching the period myself, I came across a lot of very obvious prejudices and struggles of different peoples. And so, if the time period was actually like that I thought, why ignore it? Why not actually bring it to the fore of the game itself. And I think it adds a lot of richness to the story in a way that you haven’t seen in a traditional hard-boiled or noir setting. So it kind of makes it interesting it’s not just a trite noir setting it’s a little bit more interesting than that, I think, with this interesting stuff in it.

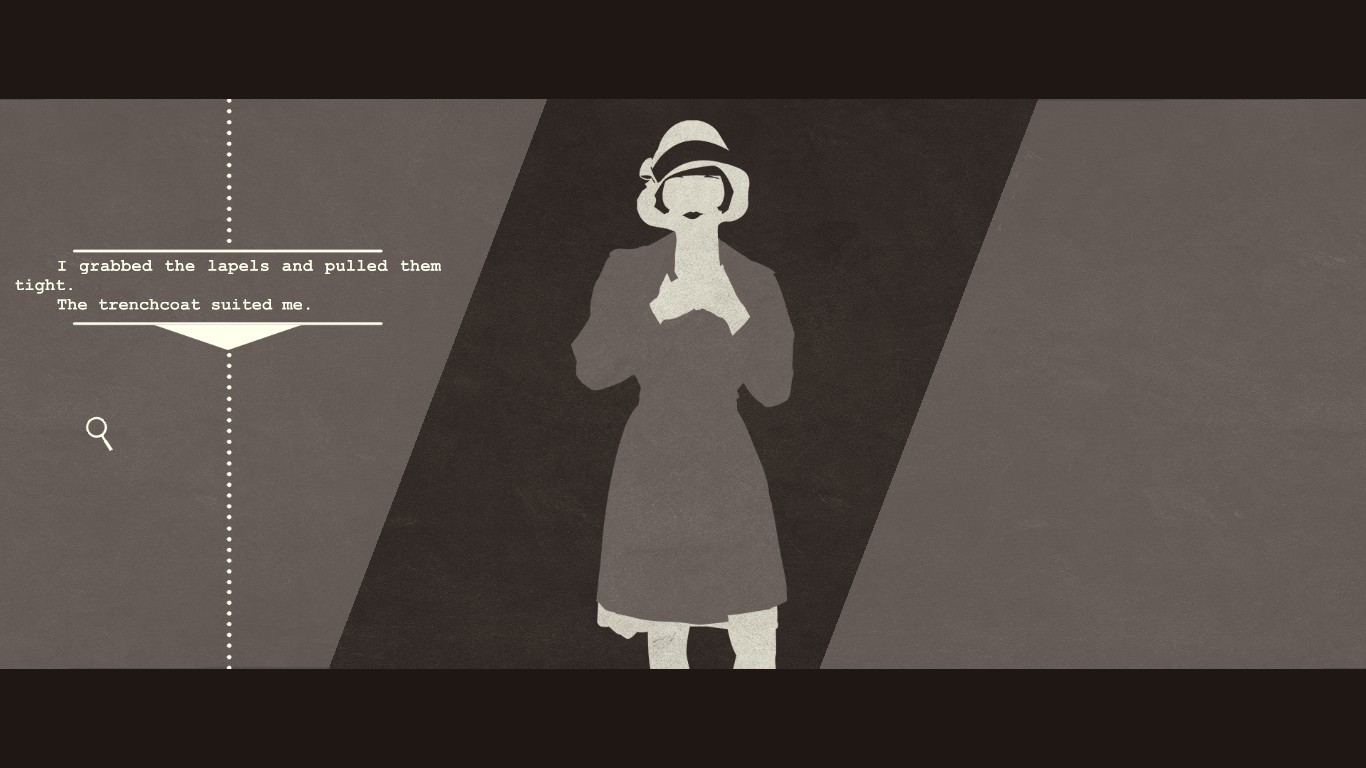

The game has a very distinctive atmosphere, from the period music to the colorization of each character, and even the scene transitions. What factored into your decision to go with the rotoscope, minimalist aesthetic?

Wander: Yeah, so the art style is mostly inspired by a guy named Saul Bass whose a poster designer. He’s most notably known work is from the fifties and sixties and seventies, and sort of onward. The part of his life that I’m taking the most inspiration from is where he was doing film posters.

He really was the person who pioneered these really bold colors, and really heavy silhouettes and big simple shapes. I mean, film posters before Sal Bass were just “hey here’s a picture of the stars in the film and a title and a bunch of credits at the bottom” and he sort of changed that into, “okay, but what feeling is this film trying to evoke?” and he found that these bold colors and these simple shapes were much better at evoking a feeling than, you know, a realistic depiction of the actors in the film, or something.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10195455/333.jpg)

If you look up Saul Bass, you’ll see that a lot of the same colors and a lot of the same shapes I’m taking them from there and using them as well. And he took his style of posters and actually moved it into intro credits for films and he was the first person to really think about intro credits as “here’s the setup for the movie.” Before it was just a couple of cards on the screen and then boom the film starts. So he thought what if the film credits are almost thematically like the mini-film before the film. And that was really really interesting and that work really did a lot to bring this new and bold and interesting transitions to films. And that’s where I take inspiration for the transitions that happen in the games. The bleed in, or the magnifying glass coming in and flipping and going out, stuff like that. And I mean those aren’t directly taken from any of the work that he did, but definitely in that style of work.

Many of the characters have very strong personalities, were any of them inspired by real people?

Wander: Yeah, I think I took a hodgepodge of people that I knew, and people that I had researched who were really important to their time period. I’ll give you an example, the main character, Phyllis Malone. I knew I wanted her to be somebody who was really breaking the bounds, you know. She was an early policewoman in a time where early policewomen weren’t that common. They existed but people didn’t really see them that often. And then she quit that job to found her own private detection agency, which was unheard of, I mean, nobody had really done that.

So I needed her to be a pioneer in some way and I looked for inspiration in other pioneers and why they became pioneers and how that helped them. Really, a lot of Phyllis’ backstory is based on Amelia Earhart, and she was the pioneer of flying for women, she was one of the first female pilots. She broke a lot of boundaries that way. What’s great with Amelia Earhart is that there is a lot of information about her. So I looked at her backstory and how did she grow up and what were the reasons that drew her into piloting and how did she grow up even before that, I mean, what was her childhood like?

A lot of Malone’s childhood is inspired by that. In fact, I mean, I wrote a lot about these characters. Each character has pages and pages of backstory that you don’t really see in the game but is important to make them feel more like a complete character. So I actually named Malone’s sister after Amelia Earhart’s actual sister and I made their childhood sort of similar.

And Amelia Earhart didn’t really have this moment, but I wanted a moment in Malone’s life where she met someone who really changed her perspective and really made her go more into police work and detective work. For that, I used a real person named Alice Stebbins Wells, and this anecdote used to be in the game, but it didn’t really fit and it made it a little bit lengthy, so I cut it.

You never actually hear about it in the game but in Malone’s backstory she meets Alice Stebbins Wells who was the first American policewoman back in the early 19… like, the teens, and she meets her randomly at a park one day and they start talking and then she goes to a lecture of hers and that’s really when her life changed and Phyllis is like fifteen, sixteen at the time when they meet and that’s really when Phyllis’ life changes and she knows she wants to be this force of change specifically in the police department.

As a narrative point and click adventure game, did you find that format to be limiting to your game design decisions?

Wander: No, I actually really like point and click adventures, especially ones that you can play without needing to know how to play a game. I really like that fact that, you know, my mom can pick up A Case of Distrust and have a really good time with it. Part of it plays like a point and click and part of it plays like you’re choosing your own path in a novel. And I think that that is a really interesting way to tell a mystery. I mean, not even in a game but just in general, this is what you would recognize as a mystery novel but you have more choice in it and it’s more you telling the story to yourself.

Then the other part of it is hunting around for clues like a detective actually would, and talking to people and getting statements like a detective would get. And that’s sort of your inventory. Those are almost, if you want to think in a traditional game development sense, those are your weapons, the evidence that you collect and the statements that people tell you. What you’re fighting, really, is lies that other people tell you. And so with those weapons that you have in your inventory, you combat the lies that other people are saying to you and once you correctly defeat a lie you sort of unravel a new of the mystery, you can dig deeper into the story.

What was the most difficult part for you in developing a branching narrative with hundreds of distinctive character responses?

Wander: Yeah, that was a really big challenge actually. It’s very hard to balance a story and an arc, and characters that grow and change with needing to allow the player to make decisions. Also, it’s hard to balance the length of text too. Someone’s playing a video game so even me, I like books, and I enjoy reading and I read a lot, I don’t want to read a novel while I’m sitting at my computer. For me, it was a balance of taking something that could be in a novel and really pairing it down to still having that style. Still having that style of writing, but not really being as long, and not really being as lengthy, and allowing the players to make choices so that they feel engaged and they feel that they’re part of it.

People have asked me, “are there thousands of endings to this game?” and the answer is no, it’s a mystery. There has to be one culprit at the end of it because if not then it’s like you as the detective effect what happens in the case. That’s not really how a detective story is told.

The interesting part is how you get there, so there’s a lot of different ways depending on who you talk to and what you say to them that branch out in terms of how you find different clues and how you get to the ending. This was a conscious choice, there isn’t any way for you to completely get stuck. But if you’re trying really hard you can make the plot much more difficult for Malone to solve, because if you’re just a jerk to everybody you meet, well they’re not gonna wanna talk to you as much and you’re gonna be in their shop and they’re going to ask you questions like “why are you here,” “what are you doing,” “get out of here, I don’t wanna talk to you anymore.” So it becomes a little bit different depending on your reactions to people.

The ending of the game leaves Malone’s future uncertain, do you have any plans to continue her story?

Wander: My first plan is to sleep after I’ve released the game. And it has been a couple weeks since the release of the game now, so I am thinking about what’s next. And like any good game designer, I have a thousand ideas rattling in my head and I’m not really sure what I’m going to do next. I will say, I spent a very long time creating these characters and like we just talked about, I barely scratched the surface of who they are and what their motivations are and where they go from here. And I spend a lot of time researching the 1920’s and San Francisco and what was going on at that time. It would be a shame, I think for me to leave it where it is. I do think that eventually, I will come back to it, the question is: am I going to come back to this as the next project, like am I going to start this in a few months or something, or am I going to take a break and do something else and then come back to it later on? And I haven’t really decided that yet.

Contact CU Independent Arts Editor Chris Koehler at christopher.j.koehler@colorado.edu.