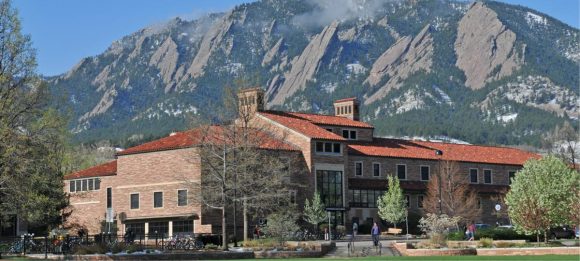

Wardenburg Health Center on main campus CU Boulder. (Photo courtesy of CU Boulder)

Most big public universities don’t keep data on student suicides, according to an investigation from the Associated Press. CU Boulder is one of them.

Of the 100 largest public universities in the U.S., over half either don’t track student suicides at all or have only limited data. Of the three universities the AP contacted in Colorado, only Colorado State University in Fort Collins keeps statistics on student suicides, while CU Boulder and Metropolitan State University in Denver “don’t have statistics or don’t consistently collect them.”

A representative from CSU Fort Collins said that their university began noting suicides in 2005, but did not consistently track data until 2006/2007.

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death among U.S. college students, and Colorado has one of the highest suicide rates in the country, with 20.5 suicide deaths per 100,000 people in 2016 according to the CDC.

Laws have been proposed to require universities to collect suicide data in Washington, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, according to the AP article, but so far none have passed.

Ryan Huff, a spokesman for CU, said that the university does not keep statistics on suicide. Huff said the reason is that while the university is typically notified of student deaths, they don’t always know how a student died, especially when the death was out-of-state.

For mental health advocates at CU, news that the university does not track suicides is concerning.

“I think it’s an important statistic to acknowledge and to identify,” said Janie Strouss-Tallman, president of CU’s National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter, an organization that advocates for mental health awareness. “In terms of evaluating how mental health is on a campus and how the mental health resources are doing, I think [suicide] is a very important statistic, so I do find it alarming that it’s not tracked.”

While the university doesn’t collect data on suicide, Huff pointed out the resources CU offers for treating mental health issues. He said counseling staff provide walk-in and crisis services at Wardenburg and the Center for Community, and there is a 24/7 support line that students can call for specific mental health and trauma-related support.

Students are eligible to receive six free counseling sessions a semester. Wardenburg does not take private insurance for therapy, so if students wish to continue after reaching their limit, they need to go off-campus.

Wardenburg also offers workshops about different mental-health topics, and there are a number of free therapy groups students can sign up for. The groups cater to a number of specific demographics, including students of color, transgender students and graduate students. The CU athletic department also has an in-house sports psychologist who works specifically with student athletes.

Multiple student groups have spoken out about long backlogs for mental health services at CU. The Daily Camera reported that mental health professionals are managing 40 percent more services than they were five years ago, and that students have criticized the difficulty of accessing prompt care.

Strouss-Tallman cited the difficulty of being able to see a counselor quickly as a “major barrier” to students receiving mental health care. Students sometimes have to get on a waiting list for their initial consultation, and after that, gaps between sessions can be several weeks long. Strouss-Tallman said the support groups were a great program but are also hard to access.

“If you don’t get in right at the beginning of the semester, there’s a good chance you’ll be put on a waiting list,” she said. “And being put on a wait list is not beneficial to people.”

CAPS director Monica Ng said that there is “no wait time” for students who want an initial session with a therapist, and that they try to keep waiting times between appointments under two weeks. However, Strouss-Tallman said that students frequently have to wait for intake sessions. The Daily Camera quoted a student who said she was turned away from the 24/7 phone line.

“Walk-in sessions, which are short, initial intake sessions, should not replace regular therapy appointments,” said Arielle Milkman, a PhD student and board member on the grad student Committee on Rights and Compensation (CRC). She also said she knows of students who have had to wait up to six weeks for follow-up visits, much longer than the stated two.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Carina Julig at carina.julig@colorado.edu.