This piece was originally printed in CU Independent’s Spring ’18 edition of Syllabus. Find it around campus.

Opinions do not necessarily represent CUIndependent.com or any of its sponsors.

In Boulder, Colorado, veins of trickling creeks, crisp air and rolling tides of golden grass give way to a spectacular diversity of life. Coyotes and deer, chickens and horses all coexist within city limits, living in the spaces that human inhabitants leave untouched for them.

Boulder is the picture of ecological diversity. This diversity stops short of its human residents, however.

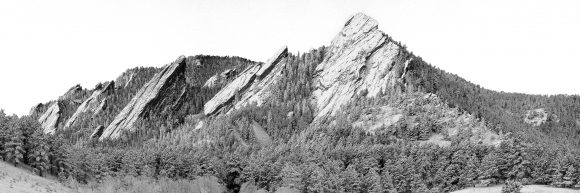

This lack of diversity is an oft-noted characteristic of Boulder. Just like the flatirons and roaming open spaces are emblems of Boulder so too is the lack of the racial, ethnic or cultural variation.

This lack of diversity is no unsolved mystery. Since Boulder’s founding in 1885 policy measures and community attitudes have resulted in an unnatural selection of residents: minorities are pushed away while white, upper-class progressives are beckoned inside city limits.

Boulder has exerted considerable effort and resources in maintaining a buffer of open space around the city’s border. In 1967, Boulder enacted the Greenbelt Amendment, which levied a tax on residents of Boulder. The funds of which went to buying and preserving land around the edge of the city. Since then, the resulting open space around Boulder has become a hallmark of the city. The preservation of this open space has had a butterfly effect on the community, impacting the housing market and racial makeup of Boulder.

The unwillingness to recognize the roots of hegemony in Boulder is the biggest impediment to mending it.

Boulder wasn’t always the whitewashed valley it is today. The Ute people populated the Boulder region and much of Colorado before whites arrived. When the settlers began trying to colonize Colorado, the Utes retaliated by killing Nathan Meeker, a U.S. Indian Agency official, along with his employees in 1854. Conflicts between the natives and settlers in the Boulder region ended in the Utes’ displacement to a reservation in 1881.

Gold-seekers established Boulder County in 1885 as a town built on mining and agriculture. The economic success of these industries brought railroad services, hospitals and schools, including the University of Colorado.

Boulder’s population skyrocketed from around 13,000 residents in 1940 to 20,000 in 1950, as a result of the GI Bill, which afforded World War II veterans financial assistance for schooling. Many beneficiaries of the bill came to Boulder to attend the University of Colorado.

This influx of residents created a backlash from the community, who called for the creation of a buffer from the influx of new, non-white residents in Boulder. The buffer would be built through housing and zoning laws restricting growth, all predicated on the idea that the land around Boulder should be pure and untouched.

The modern-day descendants of the gold seekers have a preoccupation with this idea of untainted spaces. When residents name their desire to preserve a piece of the untouched frontier, they forget Native Americans, like the Utes, inhabited the land long ago. The open space around Boulder hasn’t been untouched for centuries. The preservation of this land is now blocking low-income individuals from living in Boulder. By perpetuating a story of the history of Boulder that ignores the Native Americans’ use of the land, Boulderites can maintain a clear conscious in their decision to keep the land undeveloped.

The myth that Boulder has always been a white town overshadows the real history of the region. Again and again, the attainment of space for white residents through the displacement of minorities has been repeated.

Mexican immigration into Colorado boomed after the Great Depression, with the guest worker program which allowed foreign workers to reside in America while they were employed. This directly coincided with policy measures in Boulder that raised average home prices and kept low-income buyers out of Boulder. This, and other laws like the Greenbelt Amendment, codified the attitude that Boulderites already shared: a hesitance toward expansion and an inclination toward preserving “pure” land.

Urban sprawl, the extension of urban spaces into less dense suburbs surrounding a city, is frequently used as a code for minority and low-income migration. Urban sprawl has been prevented at all costs in Boulder. To combat this sprawl and preserve its natural land and history, Boulder purchased thousands of acres of open space through the Greenbelt Amendment.

In the 1950s, leaders fought for eco-friendly approaches to industry and transportation. This manifested in a new highway, the Boulder-Denver Turnpike, and the Natural Bureau of Standards. The ease with which people could now enter Boulder translated into a population boom that trailed well into the 1970s. Boulder’s population inflated to 72,000 people in its 25.37 square miles.

Boulder implemented the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan (BVCP) in 1970 which lays out Boulder’s plan for population and identity maintenance. The city government restricted building height in 1972 and passed the Historic Preservation Code in 1974 along with the residential growth management ordinance in 1977, all of which increase housing prices due to limited space for new buildings and high demand for residential spaces.

Boulder County’s lower-income population is disproportionately comprised of minorities—specifically Latinx residents. That minority community is greatly underrepresented in the County’s government. Only four out of 108 elected positions are people of color. While 22 percent of residents identify as non-white, only 3.7 percent of government officials claim the same identity.

The conservation of open spaces is not a solely environmental initiative. There are racial side effects of preserving this land, such as the perpetuation of a white culture that prides itself on its landscape, its morals and its purity.

The landscape of Boulder has had a heavy hand in the development of a Boulder identity. The beautifully preserved backdrop of the flatirons and the swaths of open space are what distinguishes Boulder from surrounding Coloradan cities. In fact, the rarity and majesty of these natural features are what have inspired the forceful push from residents to protect the environment.

Because Boulder is 77 percent white, its citizens rarely vote in favor of minority interests. Instead, Boulderites continue to vote in favor of open space laws, in order to keep Denver and Boulder separate.

The BVCP lays out the desire of the local government to maintain “distinct community identities.” When the plan was implemented in 1970, Denver had just experienced a major population boom, from 493,887 in 1960 to 514,678 in 1970. The plan’s goal to keep Boulder separate from neighboring cities reflects the frantic effort to maintain the homogenous, upper-class identity of Boulder, and to prevent an influx of a lower-income population.

The great irony of Boulder’s repetitive flush of minorities and low-income groups is that Boulder is a town that is characterized by its progressive, liberal politics. In 2016, around 70 percent of Boulder voted for Hillary Clinton. The citizens of Boulder vote in favor of liberal policy measures, and have no problem with levying taxes on themselves in order to aid renewable energy or open space funds.

Affordable housing, though, is one liberal ideology that Boulderites fail to address. An emphasis on affordable housing could be the key to maintaining the beloved open spaces around Boulder while also servicing Boulder’s minorities and low-income populations.

As each Monday morning begins, rays of the full orange sun track east over Colorado as do 49,000 beeping, smoking, fuming cars. Almost half of Boulder’s workforce lives outside of Boulder. Each weekday, like ants over a hill, an army of people migrate into Boulder. They stay for their work day and then retrace their commute back to their homes, outside of Boulder.

There’s a reason that Boulder does not house its own workforce. The average price of a home in Boulder city is $1,067,213, compared to the national average of $400,200. The average salary in Boulder is $60,894, only $12,252 more than the national average.

Affordable housing, by definition, costs no more than 30 to 40 percent of a household’s income. The categorical lack of this kind of housing in Boulder has pushed much of its residents outside the city’s limits.

The scarcity of land within city limits makes existing lots extremely valuable. As Boulder is built up with wealthy Silicon Valley transplants like Google, the finite lots of land are becoming even more pricey. Rich yuppies continue to flock into the city, forcing the blue-collar workforce of Boulder outside of city lines.

Old, formerly affordable, homes are being bought, gutted and fitted with state-of-the-art appliances, granite or maple countertops and glossy hardwood floors. This is lucrative for the sellers in the housing market of Boulder but devastating for low-income buyers.

The city government, in all earnestness, has installed certain requirements and goals for affordable housing. The government aims to have 10 percent of all housing be affordable, although there is no deadline on this. They have also voted to increase the linkage fee, which is a fee that land developers must pay to Boulder’s affordable housing fund per square-foot they develop.

There is a massive force fighting against the government’s efforts though. Residents of Boulder consistently meet government initiatives with heavy pushback. One proposed development at Twin Lakes in Gunbarrel was halted after the Boulder County Planning Commission voted against the plans, 5-4. The proposed development would have supplied approximately 200 affordable units.

Those that qualify for affordable housing are not oblivious to this community distaste, either.

The Boulder Affordable Housing Research Initiative (BAHRI), a project funded by CU Boulder Outreach and Engagement, conducted a report in conjunction with Thistle Communities, an affordable housing company in Boulder. The report drew upon almost 80 surveys, each sent out to a Thistle affordable home. The surveys illuminated a theme of lack of affordable housing in Boulder, as well as feelings of alienation from people of color in Boulder.

According to one researcher on the BAHRI team, residents of affordable housing communities generally don’t feel community support.

Boulderites love to tout their progressive, inclusive, love-thy-neighbor identity, but they refuse to translate this attitude into meaningful actions.

To remedy the affordable housing crisis in Boulder, we don’t need to bulldoze acres of undeveloped land. We don’t need to drastically alter Boulder’s landscape. Boulder’s residents must prioritize affordable housing.

A place to start is the zoning laws in Boulder. The current regulations for accessory dwelling units, or tiny homes, in Boulder are restrictive and unrealistic. If accessory dwelling units were more accessible, they could begin to alleviate the pressure on the housing market that currently exists. ADUs are small, affordable and sustainable, in most cases. They take up no extra land because they’re built on pre-existing lots.

It is a completely realistic goal to have at least 10 percent of Boulder’s housing affordable. All that is needed is a joint effort between community and government. Certainly an idealistic, pioneering city such as Boulder can manage to shift policy a smidge in order to accommodate the people that run it.

Contact CU Independent Opinion Editor Kim Habicht at kimberly.habicht@colorado.edu.

Contact CU Independent Assistant Opinion Editor and Columnist Lauren Arnold at lauren.arnold@colorado.edu.

Contact CU Independent Managing Editor Hayla Wong at hayla.wong@colorado.edu.