Natalie Sharp, a master’s student in the creative writing department, encourages the crowd to take action against the tax bill at the #GradTaxRally protest, Nov. 29, 2017. (Lucy Haggard/CU Independent)

For most Americans, taxes are a complicated thing to understand.

According to an Ipsos poll conducted on behalf of National Public Radio earlier this year, only about a third of Americans “know a fair amount or more” about national tax policy. The current federal tax bill being debated by Congress aims to simplify the tax filing process. However, critics say millions of Americans could be negatively affected and forced to pay more by this simplification.

People seeking higher education could see drastic changes in their financial situation, especially those in graduate school. Wednesday morning, roughly 100 people gathered outside the University Memorial Center to protest these changes as part of a nationwide #GradTaxWalkout event.

Group leaders led chanting of phrases like “save grad ed” and “the people united will never be divided.” Individuals signed petitions to be sent to national representatives. The group made a video message calling on Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) to oppose the bill, something he doesn’t seem likely to do based on the statement released from his office last night.

Members of the crowd expressed anxiety and anger about the tax bill, viewing it as a part of a negative trend against the value of higher education, both figuratively and literally. Florencia Foxley, one of the organizers of the event, and a doctoral student in the Classics department at CU, currently teaches as a graduate part-time instructor, a certificate that many graduate students on campus earn. She expressed concern and frustration about the bill’s potential change from the current system.

“The tax plan is just so blatantly an attempt to destroy graduate education, amongst many other things,” Foxley said. “A less educated electorate is more easily manipulated, and this just seems like a very clear attempt to ensure this in perpetuity. It’s just cruel.”

The crowd was mostly composed of graduate students. Amy Schmiesing, dean of the graduate school and vice provost of graduate affairs, was also in attendance, among other faculty and community members. The graduate school has been supportive for students since the tax bill was first proposed in Congress.

“CU Boulder graduate students contribute to our campus and community as students, researchers, teachers, artists, performers, and so much more, and they truly are tomorrow’s leaders,” Schmiesing said in a statement published earlier this month. “We will continue to advocate for them in every way we can and in accordance with CU’s policy with respect to federal lobbying.”

Support also came from the CU Student Government. In a pre-fall break meeting, the Legislative Council passed a resolution on special order condemning the taxing of graduate student tuition waivers. Almost every member of the council signed on as a sponsor. The resolution was one of the first in university student governments to take this stance.

What does the new tax bill include?

The bill, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, currently resides in the Senate, after clearing the Budget Committee on Tuesday. It’s a $1.5 trillion package intended for fiscal year 2018.

While it has multiple controversial provisions, including changing the partitioning of tax brackets, modifying funding for affordable housing and possible detriments to small businesses, much of the uncertainty surrounds the bill’s interaction with post-secondary education institutions. It doesn’t concern direct funding towards those institutions, which is set out in the budget. Rather, it addresses a few key programs in place that provide financial support to students and those they depend on financially.

The bill terms the consolidation and changes in these programs “simplification.” While the current process of applying for tax benefits for involvement in higher education is not quick or easy, there may be more of a negative than positive long-term impact, according to some critics.

The Senate’s version of the bill is more moderate regarding its changes on student taxpayers, as highlighted by a statement from the American Association of Universities earlier this month, a group that CU belongs to. However, there are still potential problems for students. Overall, the proposed changes fit into a larger context of less public funding for higher education, no matter the type of student.

For the sake of this article, all tax information will assume that the person is filing individually. They may be the taxpayer themselves or their parent, since many college students remain financial dependents. Many of these benefits also apply to those who are married and filing jointly, with small numerical changes, but the quality of the benefits remain the same.

What changes would student taxpayers see?

One of the most notable changes would be the elimination of the Lifetime Learning Credit, or LLC. Currently it allows for up to a $2,000 credit each year for those with less than $65,000 in modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), with reduced credit going to those with MAGIs between $55,000 and $65,000. There’s no term limit, so it can be used for as many years as they’re in school.

This impacts graduate students especially, as their schooling can take upwards of ten years in some programs, so having endless credit available allows for financial security during their potentially untraditional education timeline. The credit applies to any student taking at least one course, helping those who may be in long-term programs due to returning to school later in life as well as typical full-time students. Consequently, taking away this program would limit the accessibility of people to attend school under less traditional timelines.

Similar, but slightly different, is the American Opportunity Tax Credit, or AOTC. It allows for up to $2,500 in credit each year for those with an individual MAGI of less than $80,000, and a reduced credit between that and $90,000. The AOTC is currently limited to four years of benefits.

This assumes students graduate within four years, but that’s often not the case for those in graduate programs, as well as undergraduates, where a six year timeline is becoming the norm due to increased expense, which for many necessitates taking time off or lighter course loads in order to pay for schooling.

Under the House version of bill, the AOTC would extend to five years, but the last year would only allow for half the benefit amount. This is supposed to compensate for the elimination of the LLC, but the Center for American Progress (CAP), a left-leaning research and advocacy organization, found that it would amount to a net loss of $17 billion for students over a decade.

Under the House version of bill, the AOTC would extend to five years, but the last year would only allow for half the benefit amount. This is supposed to compensate for the elimination of the LLC, but the Center for American Progress (CAP), a left-leaning research and advocacy organization, found that it would amount to a net loss of $17 billion for students over a decade.

Besides tax credits, benefits also come in the form of deductions and exclusions. Currently a taxpayer can claim up to $2,500 in above-the-line deductions, meaning that the amount is subtracted from their income before taxes are even calculated. This deduction would be eliminated altogether in the House version of the bill. While the Senate has initially said it would retain this deduction, it could still be on the table in negotiation.

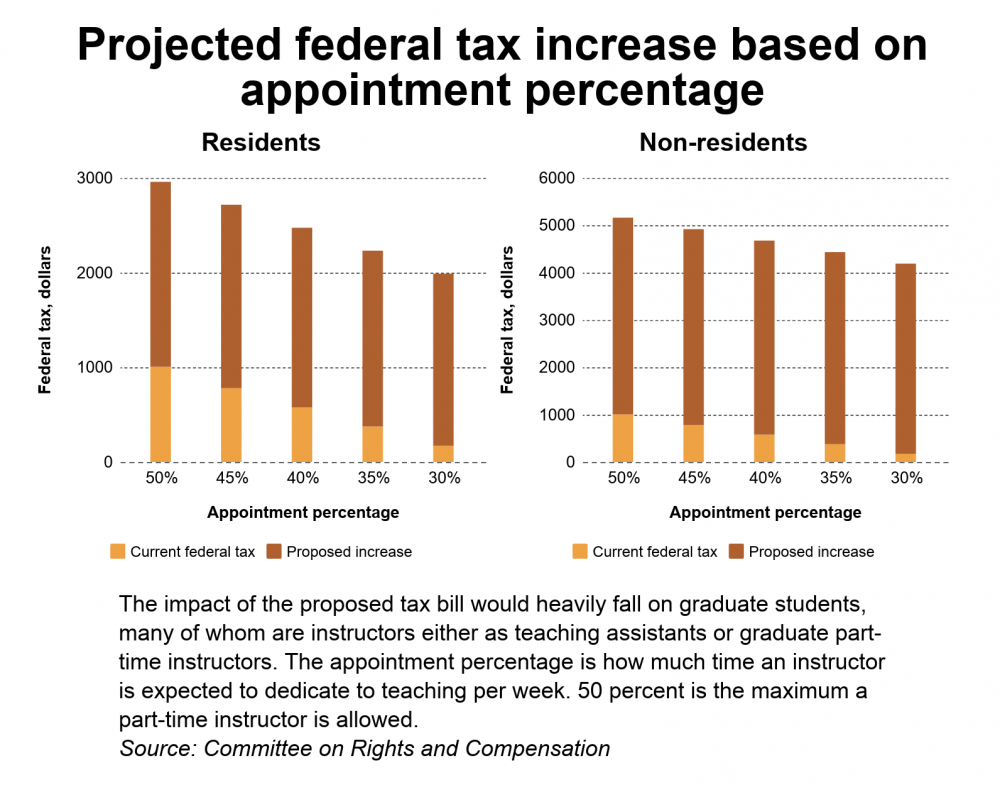

The House version also included a provision that shifted the status quo of tuition waivers, given to graduate students by their university, to being considered taxable income. Currently they’re exempted from being calculated into someone’s taxes, in order to offset the cost of graduate school. If these were to be taxed, it would mean that these students may find themselves in a higher tax bracket, thereby increasing their tax liability, or the amount they have to pay, without actually increasing their livable income.

According to analysis by the Council of Graduate Schools, a student at the University of Washington who gets tuition waivers for three academic quarters ends up keeping about 90 percent of their teaching assistant income as “take-home pay,” with the rest going towards taxes. If their tuition waivers were to be taxed, the amount of their income going to taxes would double, thus decreasing their “take-home pay” by about 10 percent.

According to analysis by the Council of Graduate Schools, a student at the University of Washington who gets tuition waivers for three academic quarters ends up keeping about 90 percent of their teaching assistant income as “take-home pay,” with the rest going towards taxes. If their tuition waivers were to be taxed, the amount of their income going to taxes would double, thus decreasing their “take-home pay” by about 10 percent.

Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey, a doctoral student in environmental studies, transitioned away from his career as an aquatic ecologist and moved with his family of four to Colorado in order to continue his studies. He said that his already low wages amount to about $2,000 a month after taxes. If the tax bill goes through as is, it could add another month and a half’s worth of wages to his tax liability.

“I can barely afford to live here as it is, and I don’t think we could afford to live here if this tax bill goes through,” Osborne-Gowey said. “I think I would have to stop the program, and that’s four years of investment that was already a substantial family decision.”

All told, these proposed changes could mean taxpayers in higher education lose upwards of $65 billion in credits, deductions and exclusions, as estimated by CAP. It’s worth noting that none of this applies to students attending law school, even if it’s through a public university.

A lot of this seems to impact grad students. What could be the effect on them?

Most attendees of a post-secondary institution, be it an undergraduate college, graduate school or trade school, would experience impacts on their finances if the tax bill passes as is. However, graduate students would likely feel the brunt of these repercussions, because of the LLC’s flexibility on years used, as well as the tuition waiver exemption when filing taxes. The House plan is a bit more strict on these points than the Senate. Yet even if some of it is implemented, it would have a significant impact on the affordability of post-graduate education.

It would also impact student’s job training for when they finish their program. Mark Pleiss is a lead coordinator at the graduate teacher program and a doctoral graduate from CU. He says that in his experience as an instructor, and in his job training graduate students to teach, he has seen students blossom in the teaching experience, with the effects carrying over far beyond their degree.

“Once you have the ability to explain the material, and teach a class, and organize a class, and manage student expectations, and manage students in general and just do all of this different work on top of your research, you build the skill set you need to become a competitive person in the [job] market,” Pleiss said.

How would it affect university operations?

According to CU’s Data Analytics, in 2017 5,581 degree-seeking students enrolled in the graduate school for a master’s or doctoral program, about 15 percent of the school’s total student population. A slightly outdated page on the graduate school website, which doesn’t note when it was posted but does say that there are 5,146 graduate students, reported that about two-thirds of these students receive fellowships and assistantships.

The office of dean of the graduate school could not be reached to verify an updated amount of students employed as teaching or research assistants. Additionally, the enrollment numbers supplied by a Data Analytics visualization don’t match up perfectly with the numbers provided in their other enrollment report mentioned above.

This aside, it’s safe to say that if graduate students can’t afford to come to universities, there would likely be a decrease in available labor to teach classes. Those who choose to continue a master’s or doctoral program could be forced to switch to part-time schooling, devoting more of their time to a different job in order to help pay for the degree.

“You have this entire ecosystem that’s thrown into disarray because students have to find ways to make up those huge costs in a way that makes their lives so much harder,” said Sara Garcia, the research associate on the post-secondary education team at CAP. “It makes it harder to finish, it makes it harder for them to pay even the best loans for fair credit in the future, and it throws the entire higher education system into a frenzy.”

How else would it affect the university, and to a larger degree, the state and national levels?

There may be repeals or rollbacks of charitable giving deductions and tax credits, which Chancellor Philip DiStefano called “tool(s) that incentivize charitable giving to support our students, research and public service” in a recent open letter in CU Boulder Today. These deductions and credits are given by writing off donations to certain organizations, including nonprofits and those educational in nature.

DiStefano’s letter estimated a decrease in $95 million in these sorts of tax credits for individuals, which could heavily influence whether or not someone donates to the university. For CU, whose Boulder campus receives about 28 percent of its funding from restricted revenue, including donations and investments, repealing the charitable giving tax credits and deductions could have a sizable impact on the budget.

“Higher education is a people-intensive business, so about 75 percent of our budget is in personnel. If things go from bad to worse, we have to look at the structure of the place,” said Ken McConnellogue, vice president of communication for the CU system. “It’s important for us to look at alternative revenue streams like fundraising, like certificate programs, things like that. We have to be creative in how we’re gonna make this thing go.”

McConnellogue pointed out that, as the Washington Post reported recently, there’s an increase in misunderstanding on who benefits from post-secondary, especially graduate, education. He said it’s easy to see a solely a private gain, something to boost a resume. But the repercussions extend beyond that, to benefit the collective.

“The work that higher ed does, providing a highly skilled workforce, doing research that changes lives and advances knowledge, it’s critical work and we [the higher ed system] are a huge economic engine not only in our state but in this country,” McConnellogue said.

The long-term effects of this tax bill aren’t clear, as these sorts of changes haven’t been seen in tandem before. That said, the Bipartisan Policy Center’s report earlier this year on the rising cost of higher education predicted that “rising college costs can be expected to contribute to widening disparities in opportunity and income over time” due to the lack of accessibility for lower economic classes.

For Osborne-Gowey, the former aquatic ecologist-turned-doctoral student, his tuition waiver allows him to conduct research on wildfires that benefits both the local and global communities.

“The tuition waiver allows me to continue to help people learn to live more safely with wildfire (a natural part of the world that is now out of whack largely as a result of our past natural resource management actions),” Osborne-Gowey said. “Without that tuition waiver, there would be that much less learning about these interactions and how to bring things back to a more harmonious way of being.”

Contact CU Independent Breaking News Editor Lucy Haggard at lucy.haggard@colorado.edu.