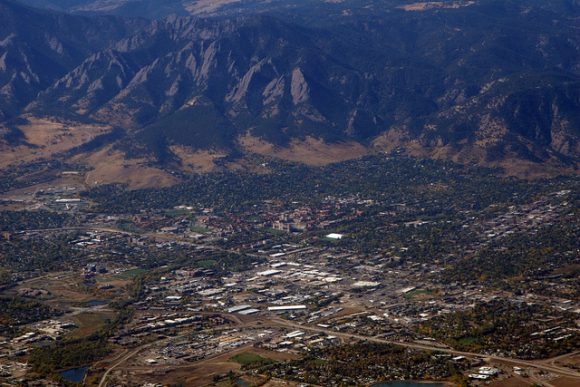

A bird’s-eye view of Boulder. (Doc Searls/Flickr)

With Boulder’s local election approaching fast, voters are gearing up to decide which five candidates will sit on the new City Council.

One thing you won’t find on Nov. 7 is a current CU student on the ballot. That might not seem weird at first, but in a town of 108,000 people, the 33,000 plus undergraduate and graduate students at CU make up the largest unrepresented minority in the city. Just like any minority, students want to have a say when it comes to the issues facing Boulder. Because they effect students heavily, topics like affordable housing and transportation are especially pertinent.

Getting elected at such a young age is difficult anywhere — young candidates are often seen as inexperienced and unaccomplished. Despite that, there are many college towns in America that feature at least one student on their city council.

Take Bloomington, Indiana, for example. The sixth largest city in the Hoosier state often has students from local Indiana University serve as council members. Currently, law student Allison Chopra sits on the council, representing the town’s 3rd District.

So why are students elected in Bloomington but not Boulder? It comes down to the rules of the election, specifically whether the city uses a ward/district system, an at-large system or some combination of the two.

In a ward system, the city is broken up into several different districts or “wards,” each with its own council member that can only be elected by residents of that ward. Political scientists often refer to this as a “Single Member District” system, the same system by which the U.S. House of Representatives is elected. During the progressive reform era (1890s-1920s), many municipalities turned away from the ward system as a means of fighting “machine” politics.

Boulder was one such place, as it switched to an at-large-system and has been since. At-large systems work by having the entire city vote for all the council members at once, much like how a state selects its two senators.

But according to political scientists, at-large systems tend to limit the representation of electoral minorities, whether it’s African-Americans, Latinos, women or even college students. The theory is that because they’re competing against the majority for every seat, it’s much harder for candidates that represent a certain minority to get elected, no matter how much support they have among that minority community. Even if a college student candidate had extremely strong support from the students of Boulder, they would likely be outvoted for every seat by the larger non-student population of the city.

“Having all at-large seats in multimember election system is fairly unusual anymore, anywhere,” CU political science professor Kenneth Bickers said. “But it’s particularly odd given the attention Boulder gives, and rightly so, to promoting diversity that it has an election system that makes it unusual for diversity to flourish on the City Council.”

In theory, ward systems alleviate this by allowing some minority communities to have at least one seat to which they can elect someone who will fight for their interests. In the 1960s, the U.S. Department of Justice pushed for more ward systems in the deep south as a way of increasing African-American representation on city councils, school boards and county offices. It’s not a perfect fix, as representation can only increase if the minority population is concentrated in one area of the city, like African-Americans were during (and still after) segregation.

College students happen to be a minority that’s concentrated into certain areas because of their need to be close to campus. In Boulder, neighborhoods like the Hill and Goss Grove are almost exclusively made up of CU students. If there were to be a district covering these two areas, students would have a solid voting majority and could easily elect one of their own, just like Bloomington’s 3rd District.

But between Boulder’s at-large system and its unusually high candidate age requirement of 21 — which disqualifies almost half of CU’s student body — it would be nearly impossible to elect a college student given the current rules.

At least two candidates in the upcoming race say they would support a change in the city’s election rules to allow for more diversity.

Matt Benjamin, a former CU student and programs manager at Fiske Planetarium, has made pushing for districts a core part of his platform.

“Certain parts of Boulder have different character, they have different needs,” Benjamin said in a phone interview. “Sometimes when the council makes city-wide decisions, those individual needs of neighborhoods and subcommunities get lost or diluted in the process.”

Benjamin believes Boulder should switch to a hybrid system with four districts, four at-large seats and a directly elected mayor. As of now, the City Council chooses one of its members to serve as mayor. He also believes any change to the electoral system should come through a ballot initiative, voted on by the people of Boulder.

Benjamin has stated that he would be open to students taking advantage of this new system to get more representation on the council.

“Most, and I could even say all CU students when they come to Boulder, this is the first community that they get to make their own,” he said. “It’s vital that we as a city enable those that care and want to be in this community to participate as much as possible.”

Another candidate, Adam Swetlik, says a ward system wouldn’t be perfect, but would be the best way to boost diversity on the council.

“I think that’s the best and most democratic way to solve some of our problems right now, I just want there to be a conversation about what both sides of the fence would look like before we actually make that decision,” Swetlik, a 2010 CU graduate and current doorman at the Walrus Saloon, said.

At 30, Swetlik is the youngest candidate running, a fact he believes connects him more with the student demographic but also makes his chances of winning slimmer.

“I’m the least far-removed from the problems of college life, and I’m still dealing with the fact that Boulder is not a friendly place to establish a lifestyle after college,” he said.

Both candidates also noted that a big step towards better representation for CU students would be for them to become more active and aware of local politics. Swetlik pointed out that the turnout for college voters in Boulder’s local elections is one of the lowest in the city.

If Boulder elects candidates like Benjamin and Swetlik, it could signal that change is coming. But until then, students may find themselves excluded by the city’s legislative body and its unique rules. The problem will only be amplified if student grievances against city government continue to rise. Voters will decide what direction they want to go on Nov. 7.

Contact Assistant Sports Editor Kyle Rini at kyle.rini@colorado.edu.