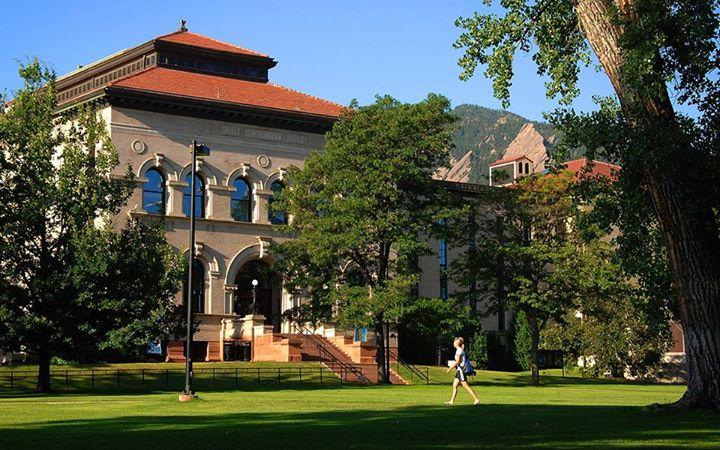

The University Theater building at CU Boulder, which is now showing the play ‘The Adding Machine’ written by Elmer Rice in 1923 and directed by Cecilia J. Pang. (Photo Courtesy of CU Boulder)

Everyone has their own theory about life’s purpose, or lack thereof, and what happens after death, but no one can possibly prove any of these theories. Perhaps religion or other beliefs can fill the void of oblivion about human existence that we all possess, but The Adding Machine dives straight into the darkness. The 1923 play by Elmer Rice explores human existence through a nihilistic and critical lens. Director Cecilia J. Pang’s adaptation of the play, which opened Friday night at the University Theater, employs intricate choreography and just enough comedic relief to set the stage for extremely entertaining existential reflection.

The play revolves around the life, death and reincarnation of accountant Mr. Zero. After 25 years of employment at a large company, he loses his job when he finds out that an adding machine, which can be operated by a high school girl, will replace him. In a fit of rage, he murders his boss. After being tried and sentenced to death, Mr. Zero soon finds himself in a heaven-like afterlife. While there, he meets a religious fanatic that was also put to death for murdering his mother. The man, named Shrdlu, is deeply unhappy that he has not been banished to the burning pits of hell for his sins. Soon becoming tired of the monotony of eternal bliss, the tired soul of Mr. Zero finds out that he has already lived countless other lives and will be returning to Earth to start all over again.

The play is essentially a criticism of industrial capitalism. It suggests that under its system people are treated as cogs in a machine and that life repeats in a monotonous, never-ending cycle. It also pokes fun at humanity’s blind and naïve hopefulness. When Mr. Zero is forced to reincarnate, he willingly follows a girl named Hope, clearly a metaphor, back to Earth because doing so is his only option.

On opening night, the CU theater department showed their expertise in acting, choreography and visual aesthetic. The 15 actors in the production delivered prose with conviction and performed complex movements with ease. Although the overall message of the play is dark, there was just the right amount of comedic relief to make it palatable. Aside from the very engaging and occasionally funny dialogue, much of the actors’ expression was physical. Throughout the play, the choreography was very mechanical and synchronized — like a machine.

It seemed that the play was just as much mentally stimulating as it was visually. The set was minimal, but portrayed an industrial modern aesthetic that helped to convey the overall message. The only props were a few iron chairs, a table, neon light and a large circular tunnel that was used as the entrance to “Elysian Fields,” or the afterlife. Many of the actors were used as props themselves. Near the end of the play, the actors spell out the word “HOPE” with their bodies. The minimalism of the set, as well as the costumes, fit well with the nihilistic nature of the whole play.

Like all great works of art should do, this play was cathartic. I walked out feeling pensive yet emotionally refreshed. It triggers deep thought about human and cosmic existence and the purpose of it all. This adaptation of The Adding Machine was successful in creating something visually appealing and inspiring mental stimulation. Sadly, the theater was half empty, and on opening night! Fortunately, there will be more opportunities to see the play until Oct. 8.

Contact CU Independent Arts Staff Writer Grace Harper at grace.harper@colorado.edu.