Contact CU Independent General Assignment Editor Andrew Haubner at andrew.haubner@colorado.edu.

There is a fountain at the University of Colorado at Boulder that sits just next to the University Memorial Center and is almost always struck by sunlight. If you were to walk by it on any given day, you might be treated to a variety of opinions. It could be Evangelical Christians quoting scripture, or it could be the school’s Black Student Alliance standing in solidarity with advocacy groups at the University of Missouri.

Whatever the viewpoints are, and whatever yours might be, they’re all welcome in the fountain court. Since it was built, the fountain has been a haven of free expression and speech, devoid of censorship or ostracism. But what those advocates might not know is that there is a plaque that rests on a column just in front of the entrance of the UMC. That plaque is unknown to many, and holds the key to the very essence of the American spirit. It honors a man that paid a heavy price for freedom, a man whose influence is still being felt today.

His name was Dalton Trumbo — screenwriter, Communist sympathizer and free speech advocate. But perhaps most importantly, member of the Hollywood 10.

Even now, in 2016, Trumbo’s name inspires both admiration or aversion. Some, to this day, admonish him for his ties to the Communist Party, of which he became a member between 1939 and 1943, or believe him to be a Stalinist sympathizer because of works he appeared in such as ‘The Russian Menace.” Others celebrate his staunch defense of freedom of expression and association.

Trumbo was a student at the University of Colorado for two years before leaving for Los Angeles to pursue his career as a writer. The Montrose, CO native soon became a fixture in what can be considered the golden age of American cinema, writing classics such as A Man to Remember and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. But the Cold War cast a shadow over Hollywood, leading to investigations into the personal beliefs and associations of various film luminaries, spearheaded by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Trumbo, along with nine others, became known as the Hollywood 10, and were blacklisted from Hollywood and forced to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee on their suspected Communist affiliations.

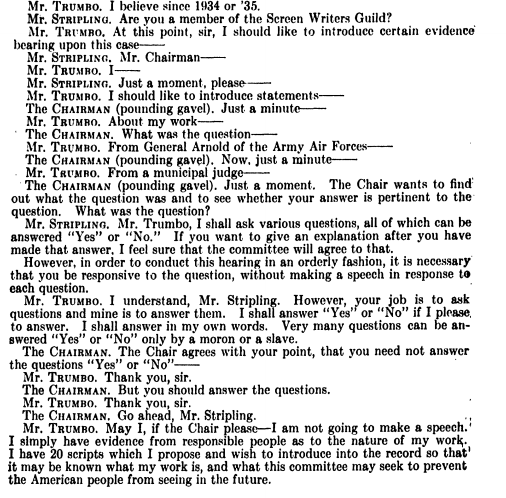

It was during this time that all but one member of the 10– Edward Dmytryk admitted his affiliation and testified three years after the blacklist’s creation–refused to testify to the committee. Trumbo never wavered, spending 11 months in a federal prison for being in contempt of congress. During the 1947 proceedings, the screenwriter defiantly stood before the committee and refused to give names of those associated with the Screen Writers’ Guild who might have ties to Communism. It kept him on the Hollywood blacklist for over a decade.

A transcript of Trumbo’s testimony before the House un-American activities committee. (CU Norlin Collections)

It was at that time that Trumbo wrote some of his finest works: Roman Holiday (1953), The Brave One (1956), Exodus (1960), and Spartacus (1960). All of those works were penned by the Montrose native, but because of the blacklist, he had to have a front or a pseudonym. Eventually, he was given full credit once the Red Scare had all but ended.

It is not disputed that Trumbo was tied to Communism during this time, but it was what he, and the other members of the Hollywood 10, did afterward that led CU students like Kristina Baumli and Lewis Cardinal to advocate for naming the fountain after him in 1992.

Renaming The Fountain

“It was never dedicated before, it was just the plain old fountain,” recalls Baumli, who was a graduate student at the time. “It was just there and they had just changed the name of Cheyenne Arapahoe, and I thought it was a pity that there was nothing on campus named after Dalton Trumbo. Nobody even knew he went there.”

“One of the features of the Hollywood 10, was that they said, ‘we are going to stand, we are not going to take the fifth, we are going to take the first,'” she continued. “By doing this, they risked contempt of court, but also risked their lives because taking the fifth was a sure defense. They knew they were risking their careers to protect the first amendment.”

Cardinal, with whom Baumli fought for the fountain rededication, was drawn to the same story of standing in solidarity with those whose viewpoints might have been unpopular, and defended their, and his, right to be able to have them without fear of retribution.

“It was the issue of principle and the cost of standing by those principles,” says Cardinal. “As Americans, that is not only a very American idea, but a very western and democratic principle that you fight throughout all democracies.”

By the time the students had gotten together to propose this change, Trumbo had long since passed, having died in 1976. But his wife, Cleo Trumbo, was still alive, and she was the first person to talk to about using Dalton’s name to dedicate the fountain. Baumli went to a CU professor, Bruce Kawin, who served as a guide for the students in their pursuit to honor Cleo’s late husband.

“(Bruce) said that the first thing we had to do was to get permission from his widow, because without that, you can’t do it,” Baumli recalls. “And so we started a letter-writing campaign, so I wrote to Cleo Trumbo and got her permission.”

From there, things started to pick up steam, and fast. Kawin suggested that Baumli and Cardinal get in touch with various Hollywood luminaries to try and garner support from them.

“I suggested that Kristina call Steven Spielberg, and she did,” remembers Kawin, who is now retired. “He went along with that, and then we got Kirk Douglas and the rest of the Hollywood 10, except for Edward Dymytryk.”

Kirk Douglas, in particular, is remembered fondly by Kawin, Baumli and Cardinal. He was the star of Trumbo’s film Spartacus, and helped break the blacklist by giving Trumbo full credit as a screenwriter. At the time of the fight to rededicate the fountain, Douglas was made aware by members of the Trumbo family, and was present for the fountain rededication ceremony.

“We got a lot of attention, especially when Johnny Carson had Kirk Douglas on and Kirk was talking about our project in a really big way,” Cardinal explains. “That rippled Boulder and Colorado in a really big way. We thought, ‘Oh my god. Kirk Douglas talking about these students and the University of Colorado at Boulder remembering and trying to honor Dalton Trumbo.’”

“As actors, it is easy for us to play the hero,” Douglas says. “We get to fight the bad guys and stand up for justice. In real life, the choices are not always so clear. The Hollywood blacklist, recreated powerfully on screen in Trumbo, was a time I remember well. The choices were hard. The consequences were painful and very real.”

Eventually, endorsements began flooding in for the naming of the Trumbo fountain. From the Rocky Mountain News to Lauren Bacall, all that was left was the final approval of the Board of Regents, who had already pushed the subject back once, prompting an op-ed column from the Entertainment Editor of the Colorado Daily, Bronson Hilliard. Hilliard, who was a film buff and supporter of the fountain rededication, realized that there was still some controversy regarding the Trumbo name, and its impact in post-Cold War America.

(Daily Camera/CU Norlin Collections)

“We could not get the Regents to hear us. They would not meet with us,” Baumli remembers. “That was their political way of stalling us. the political entities were giving us mixed signals and so when we finally got the Regents to vote on it, Ted Turner said that he would be on campus for the meeting with all the cameras wondering why they wouldn’t meet with us and then they agreed to meet with us. That’s when I knew it was finally going to happen.”

“There were still some people here who had very strong feelings in both directions about Dalton Trumbo,” says Hilliard. “The position that those of us in support of naming the fountain after him took was ‘he stood up for his right to believe what believed, which is not a crime in America nor should it be nor should it ever be.'”

As Hilliard and the others first realized, the debate was more about the ideals than the man. Was he a Communist or the most true-to-form American? Even today, the argument on both sides still persists, and there still lies a subtle irony to what the Hollywood 10 was fighting so ardently for. In supporting Communism and Communist regimes, people like Trumbo were indirectly supporting groups that actively oppressed free expression. Yet they fought, and went to jail, in the United States for that very right that was being suppressed by those they supported. What many still wonder is what to make of Trumbo, and what element of that contradiction should be more important.

“Yes, Dalton Trumbo was a communist,” explains his daughter, Nikola Trumbo. “He believed that he had every right to be a communist if he wanted to be and in fact, he did. What’s interesting to me is that the period was really successful because today people still believe that these guys were followers of Stalin who were out to overthrow the government. It was simply a political party and pro-labor belief system.”

(Daily Camera/CU Norlin Collections)

Hilliard believes something similar, arguing that there was a degree of naivety by Americans who supported a Soviet Union that they didn’t fully understand. It is worth noting that during World War II, Trumbo wrote the screenplay for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, which was lauded as a patriotic, pro-American film. But perhaps greater than the debate over the contradictory beliefs of Trumbo and his compatriots is how their legacy endures.

By a vote of 6-1, the Board of Regents officially passed the motion to rename the fountain court outside of the UMC after Dalton Trumbo. All but one member of the Trumbo family came out to see the rededication. Nikola Trumbo, like her father before her, stayed back in response to Amendment 2 passing in the state of Colorado. Nikki Trumbo, who is lesbian, protested the basis of the decision, which prevented equal protection status among the homosexual community. It was at the rededication that the family read a statement from her, one that advocated for the right to be treated as equal, even though the community was different, something that didn’t sound too dissimilar than what her father fought for four decades earlier.

“When [Trumbo’s] family came out, we gave them a moment to stand in front of the fountain,” Cardinal recalls. “And then Kirk Douglas comes up, and he just stands there as well, just stood in front of it and I thought that was very powerful. I’ve carried Trumbo with me with everything that I’ve done in my life.”

In addition to the rededication, a colloquium was created on campus to discuss first amendment rights, the film industry and the legacy of Trumbo. Some of the very same well-wishers who helped Baumli, Kawin, Cardinal and the rest came to Boulder, honoring a man whose name was finally to be remembered on CU’s campus.

On Feb. 3rd, the film Trumbo premiered in Boulder for the first time at the CU International Film Series. In a fitting end to the story of how the fountain was named, Bruce Kawin introduced the movie.

Trumbo Today

Twenty-three years later, the fountain court remains a place for free expression, and, occasionally, lively debate. Any type of viewpoint is accepted there, even if it is something that is considered divisive or even unanimously frowned upon. That is the very essence of the Trumbo fountain, and a positive reminder that the legacy of the Hollywood 10 endures to this day. And it goes beyond Boulder.

The 2016 election cycle has become fraught with divisive rhetoric on both sides of the aisle, whether it be policy based or rooted in socioeconomic cleavages. Cable networks and newspapers endorse candidates as they always have, trying to frame the debate in favor of the politician of their choosing. More often than not, opposing views are shut out, giving way to one-sided news consumption and a lack of desire for the other viewpoint to be expressed.

It is during this time that the Trumbo Fountain Court remains that much more necessary and vital to the American way of life. No view is too extreme in that space, and never will a view be shut out as long as it’s protected by the constitution. It is there that Dalton Trumbo still holds sway, promising those who are willing to express themselves that it is okay to do so in that space, and not fear retribution.

If there was one thing that Cardinal, Hilliard, Baumli would say to those protesting in the fountain court, it would be this:

“Many ideas fell here as many many suffered for your right to speak.”

“If you take time and build a coalition to change things, very strange things can happen.”

“Be prepared to speak your mind and let others speak theirs.”

And as the Black Student Alliance, Christian advocates, and any other group openly express their views in that fountain court, a small plaque faces them, as it always will. It reads:

“Dalton Trumbo

1905-1976

CU Student

Distinguished Film Writer

Lifelong Advocate of the First Amendment”

Mitt Romney supporters stage a counter rally at the Dalton Trumbo Fountain following President Obama’s reelection event on the Norlin Quad. Sept. 2, 2012 (Nigel Amstock/CU Independent File)