Top Stories

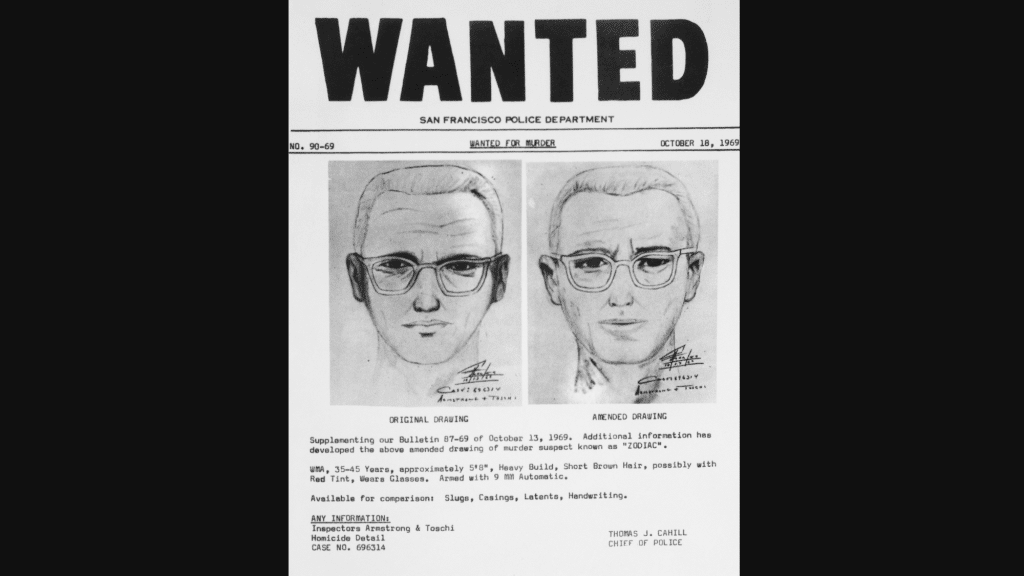

The Zodiac Killer case remains one of America’s unsolved mysteries, having captured the attention of true crime enthusiasts and investigators for over five decades. If you are searching for the most recent news, updates, and developments related to the Zodiac

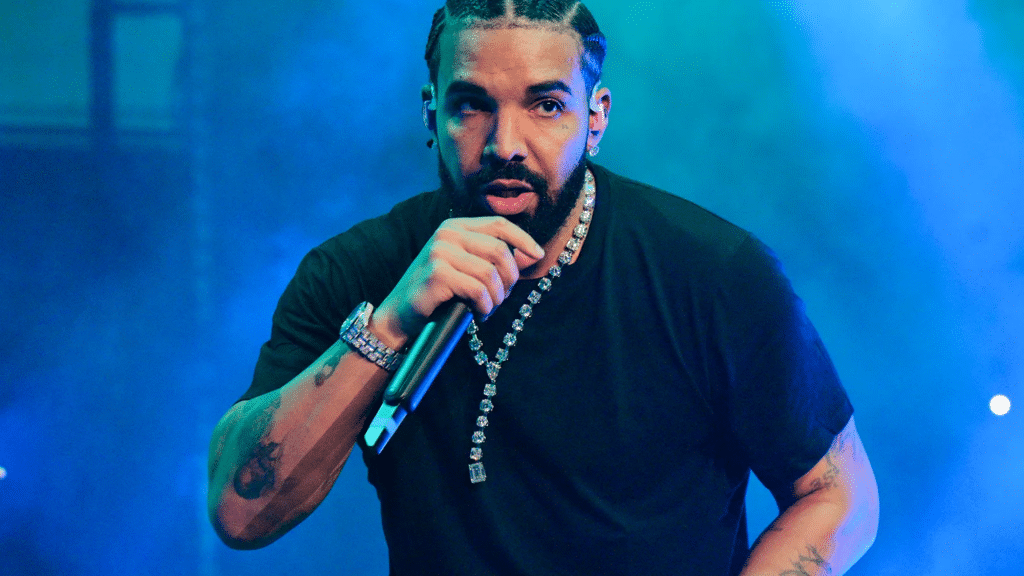

Are you curious about how many albums Drake has released so far? We have got you covered! From his start on Degrassi to becoming one of the biggest names in music, Drake has dropped hit after hit. But with studio

LATEST

Top Stories

If you want to build a fitness app, you’re entering a busy but profitable market. The main challenge is making fitness software that people use regularly, and not one they download and ignore. This guide explains what to expect from

LATEST

Top Stories

An ID scanner works by quickly capturing data from government-issued IDs, cross-checking details against advanced databases, and using multiple detection layers to spot counterfeit documents. Systems like these help venues at festivals, bars, and events verify age and identity accurately

Welcome to cuindependent, your space for bold ideas, fresh perspectives, and engaging stories. We bring you content that informs, inspires, and sparks conversation.

Stay connected — subscribe to our newsletter and never miss an update!

Explore

Our Picks

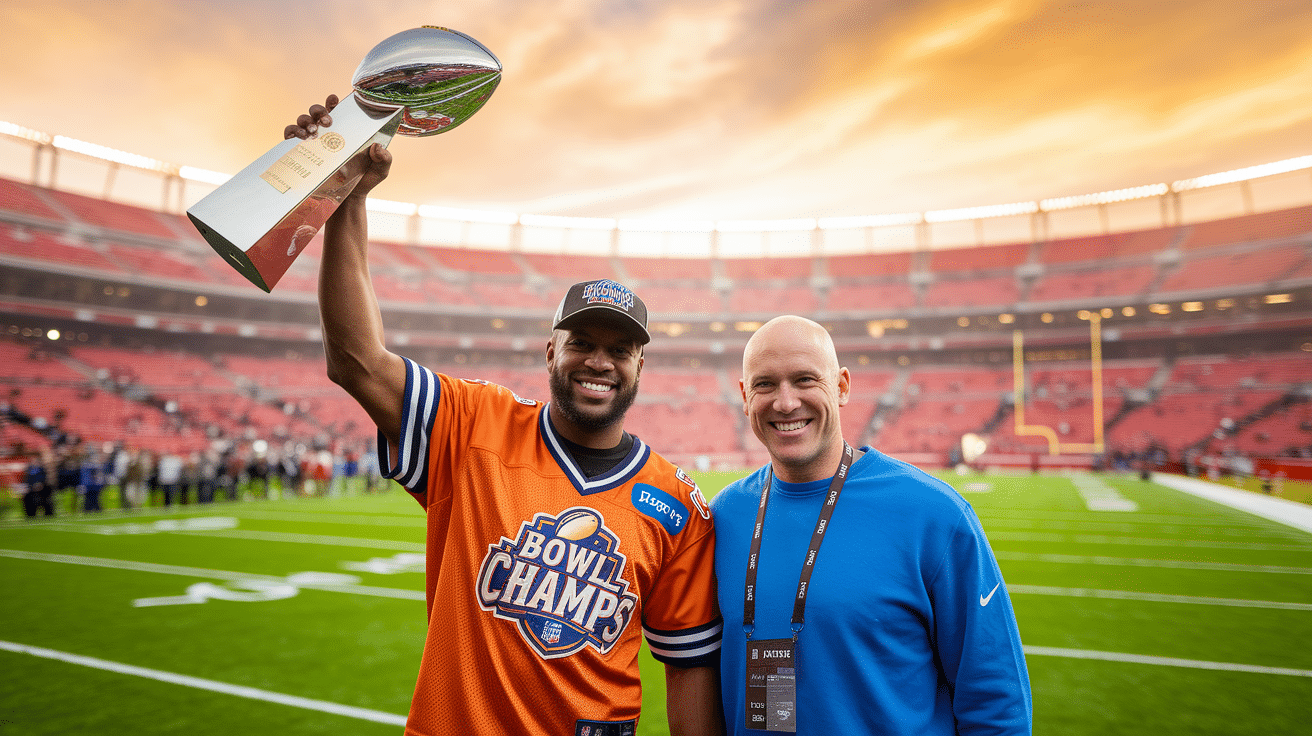

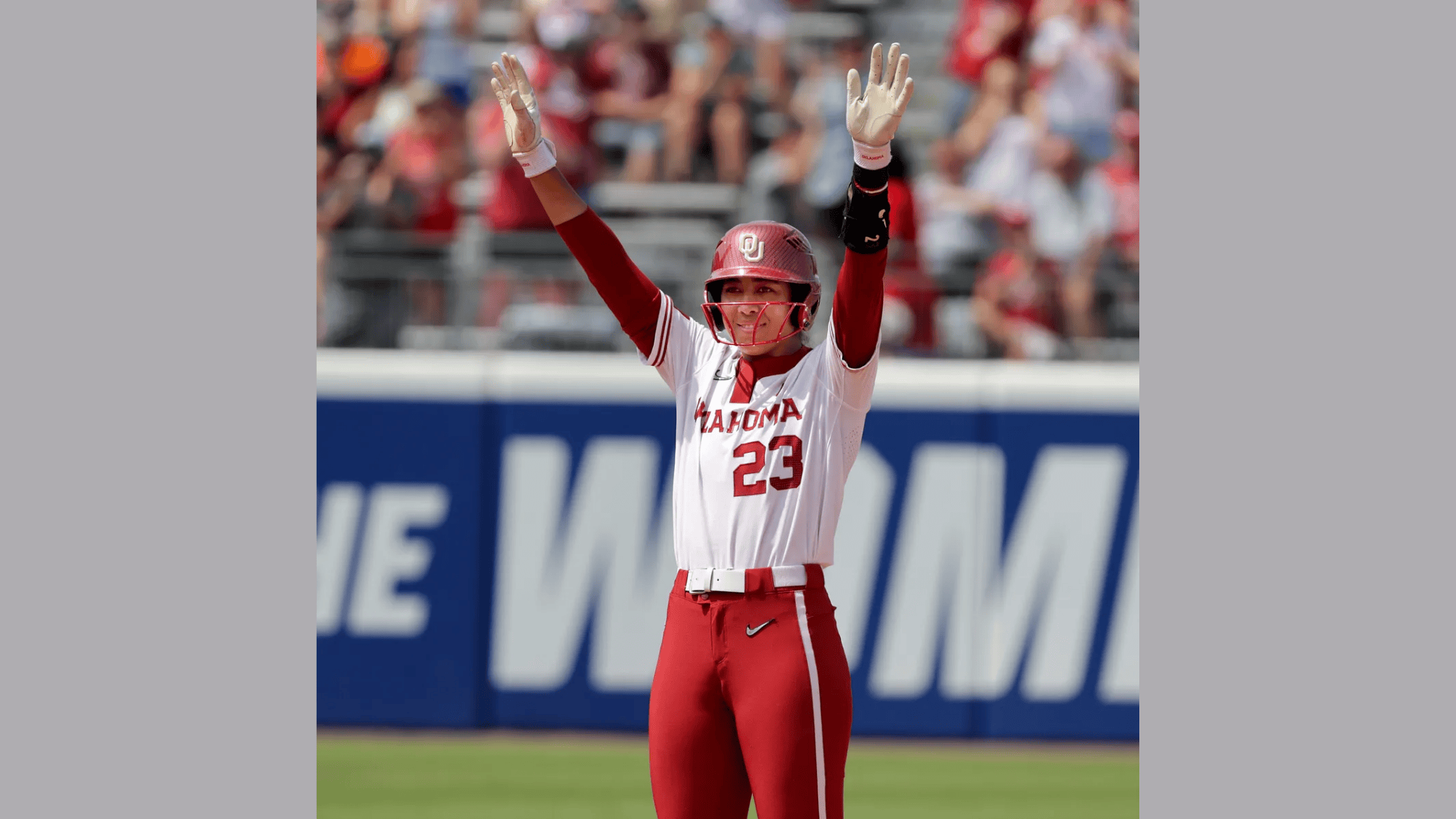

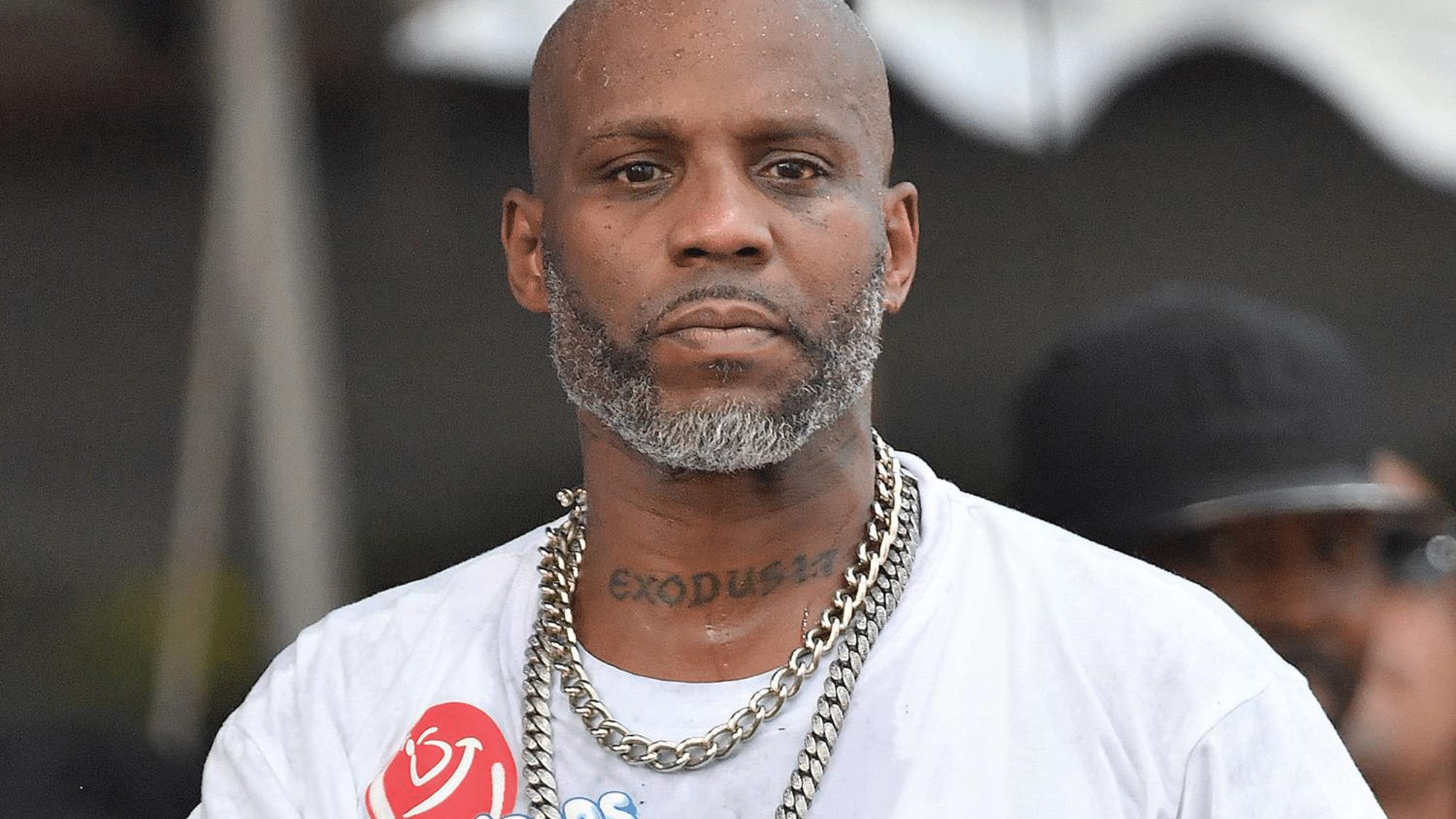

From inspiring artistry to achievements in sports and beyond, we bring the highlights.

A curated view of stories shaping conversations across fields today.

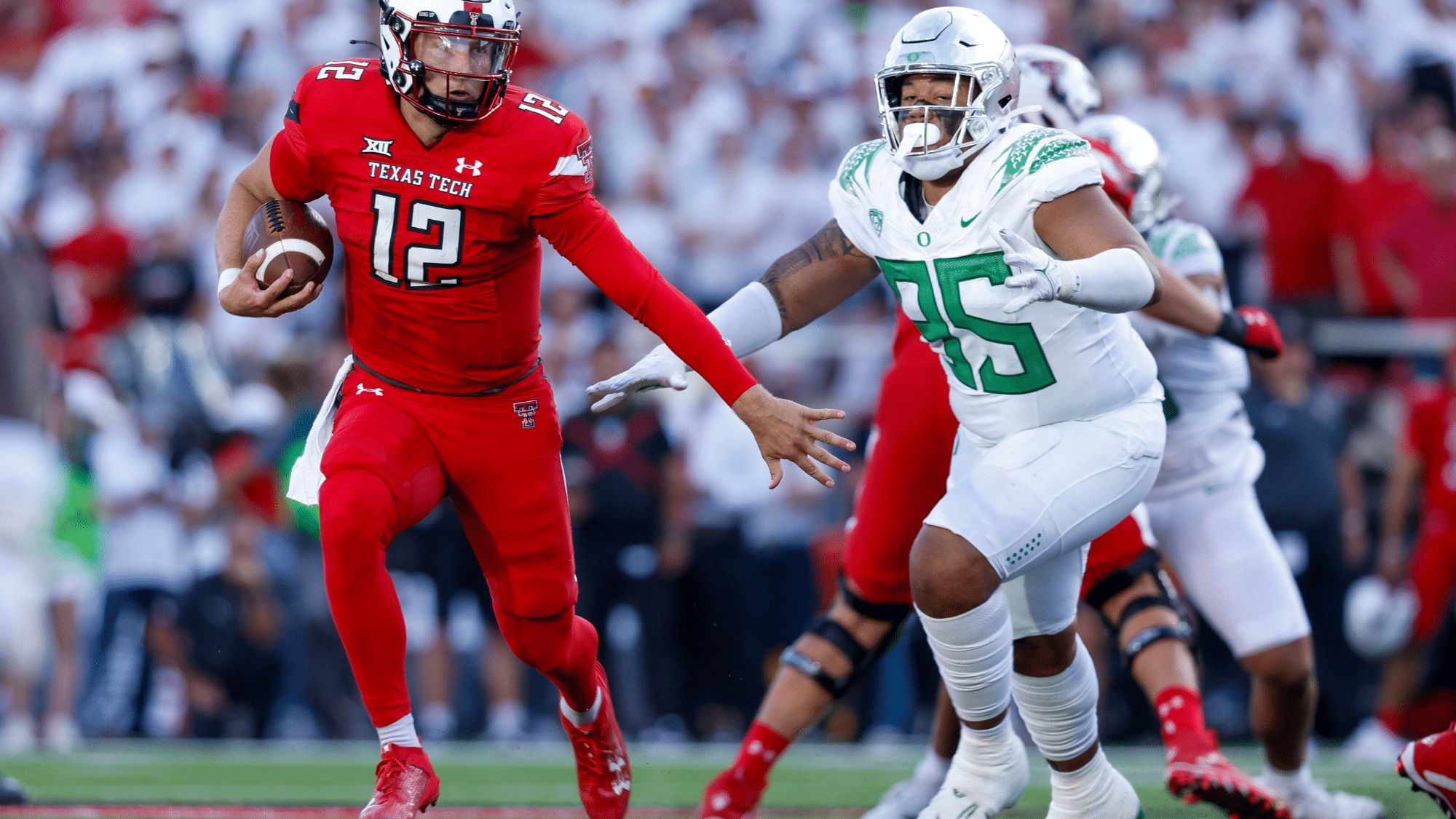

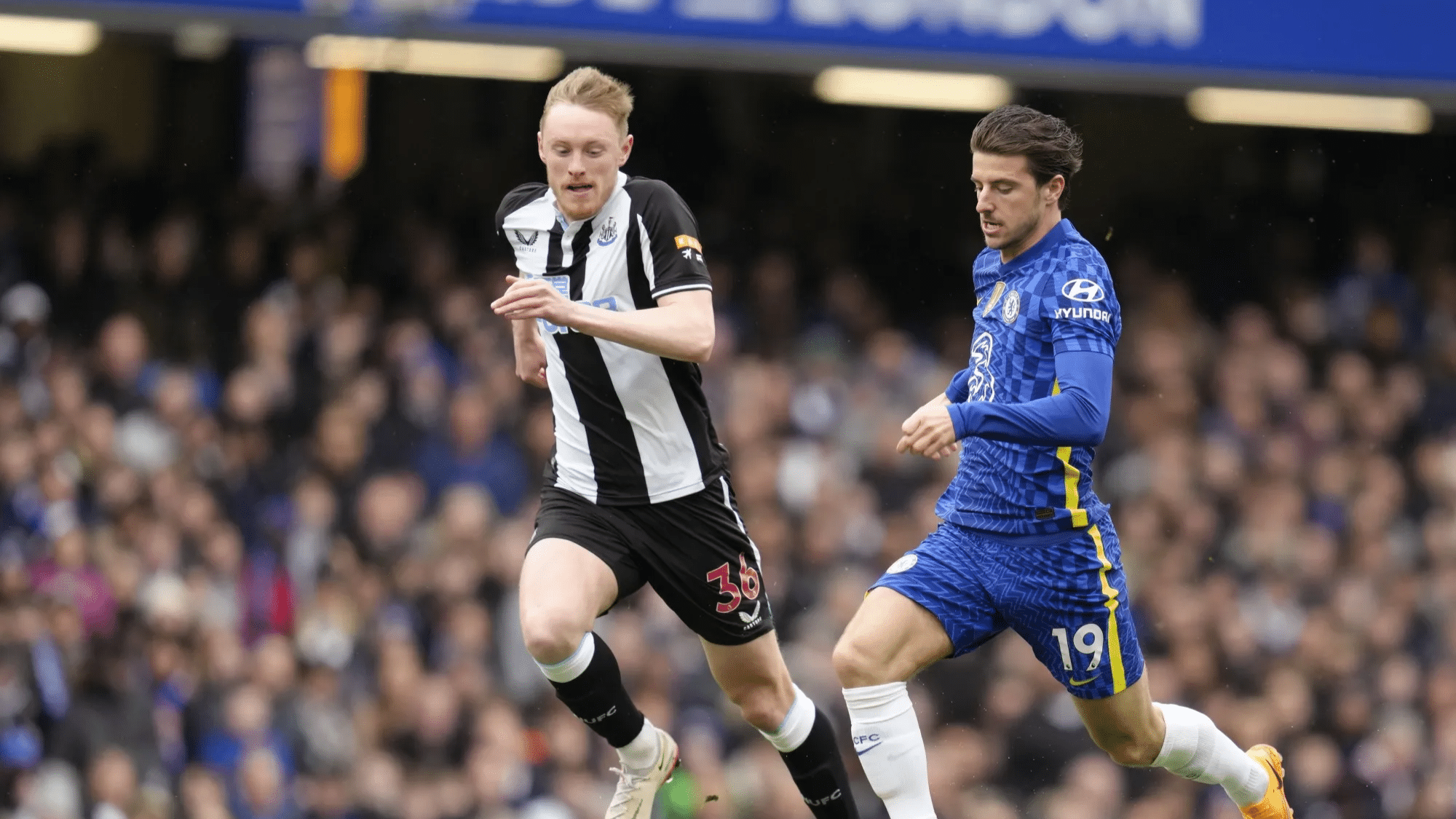

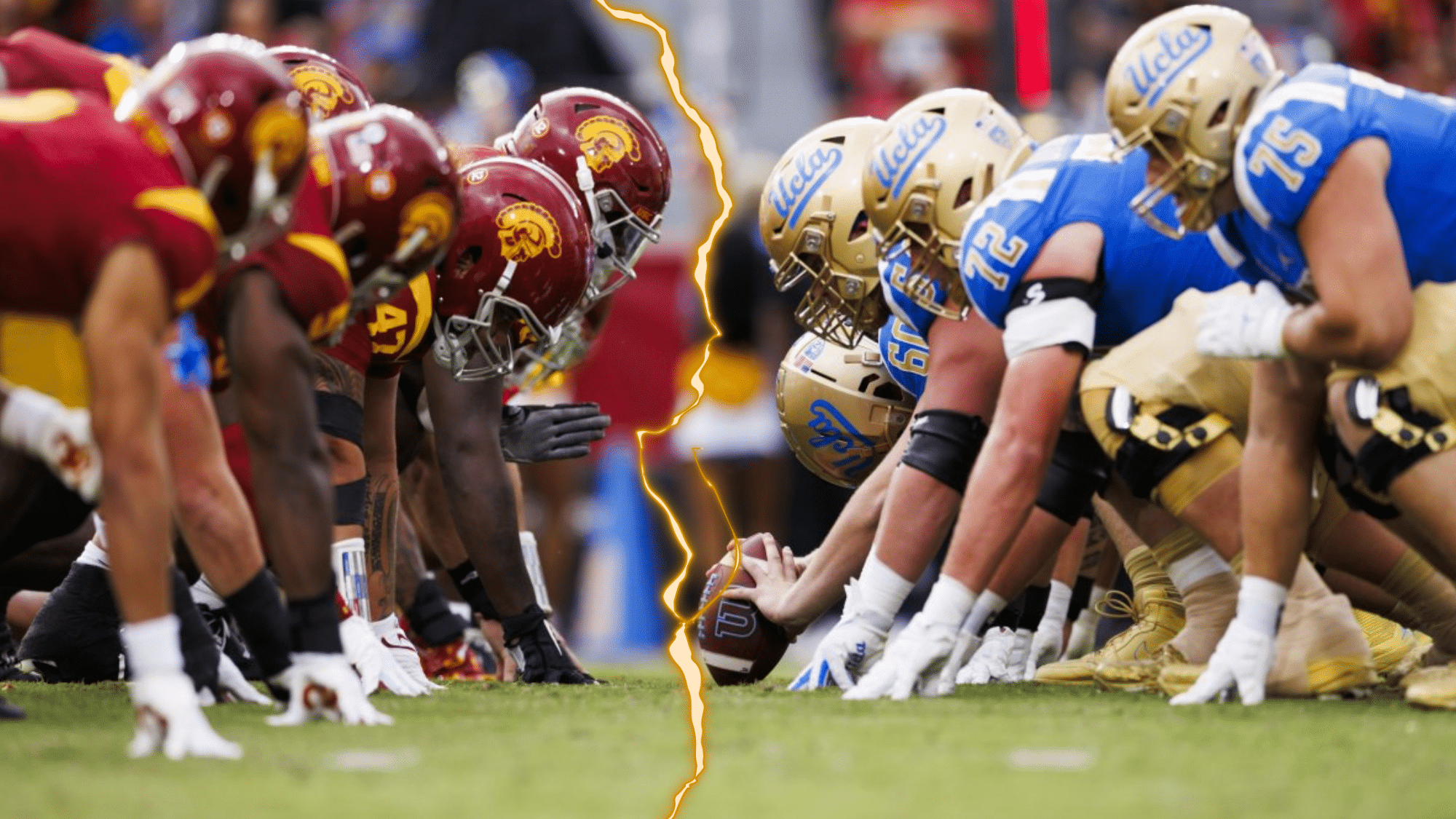

Some games aren’t just played, they are felt in the soul. These iconic rivalries go beyond the scoreboard, turning into battles of pride, passion, and identity that echo across generations. Whether it’s football in Argentina or cricket in India, these matchups light up stadiums, stir entire nations, and write unforgettable chapters.....

Fall is a magical season filled with vibrant colors, changing leaves, and endless creative inspiration. For teachers and parents, it’s the perfect time to introduce fall art projects that help children explore textures, colors, and nature while developing fine motor and creative skills. If you’re planning a classroom craft or.....

more

Meet Our Team

At CU Independent, we’re committed to delivering real, bold, and honest stories. Get to know the passionate team behind the content!

Samantha Lee

(Editor-in-Chief)

Dr. Alex Thompson

(Senior Features Writer)

Meet Our Team

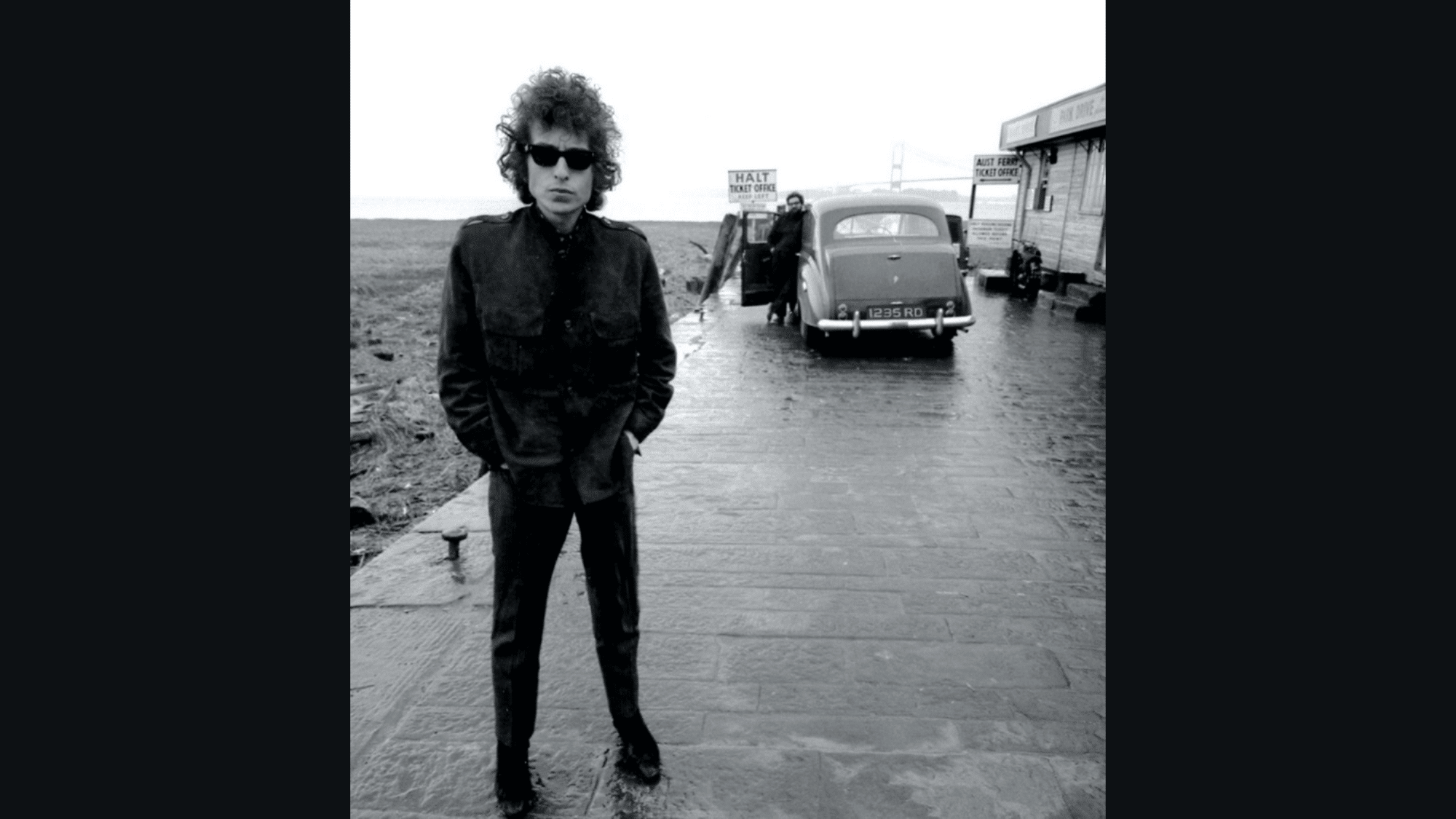

Hootie & the Blowfish is a beloved American rock band, best known for their chart-topping hits in the 1990s. Formed in 1986 in Charleston, South Carolina, the band quickly rose to fame with their unique blend of pop, rock, and blues. Their catchy songs and relatable lyrics connected with fans, making.....

Healthcare systems around the world face increasing pressure from rising patient demand, longer life expectancy, and a shortage of primary care physicians. Communities need providers who can deliver consistent, high-quality care while also building long-term relationships with patients. Family Nurse Practitioners (FNPs) have stepped into this role with confidence and skill......

Families judge a car by how it handles the real world. School runs, grocery trips, late soccer practices, and weekend road escapes ask a lot from one machine. Reliability keeps those daily plans intact. When a vehicle starts every time and stays out of the shop, it lowers stress and costs......

A healthy smile is built on small habits you repeat every day. The good news is that most of these steps are simple and low-cost. With a few tweaks to brushing, flossing, diet, and checkups, you can cut your risk of cavities and gum disease and keep your breath fresh. Brush.....

Our Contributors

As Seen On