Top Stories

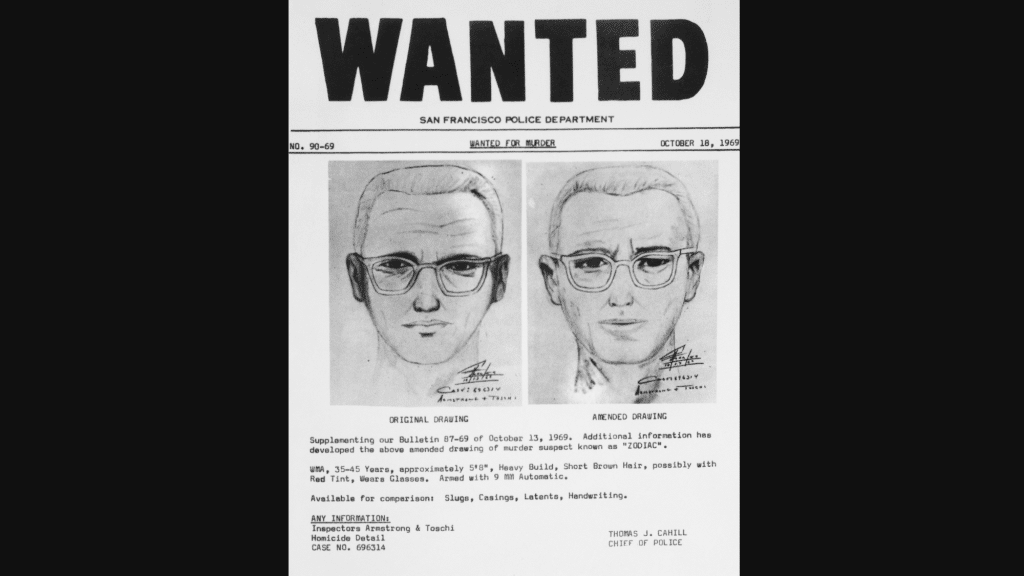

The Zodiac Killer case remains one of America’s unsolved mysteries, having captured the attention of true crime enthusiasts and investigators for over five decades. If you are searching for the most recent news, updates, and developments related to the Zodiac

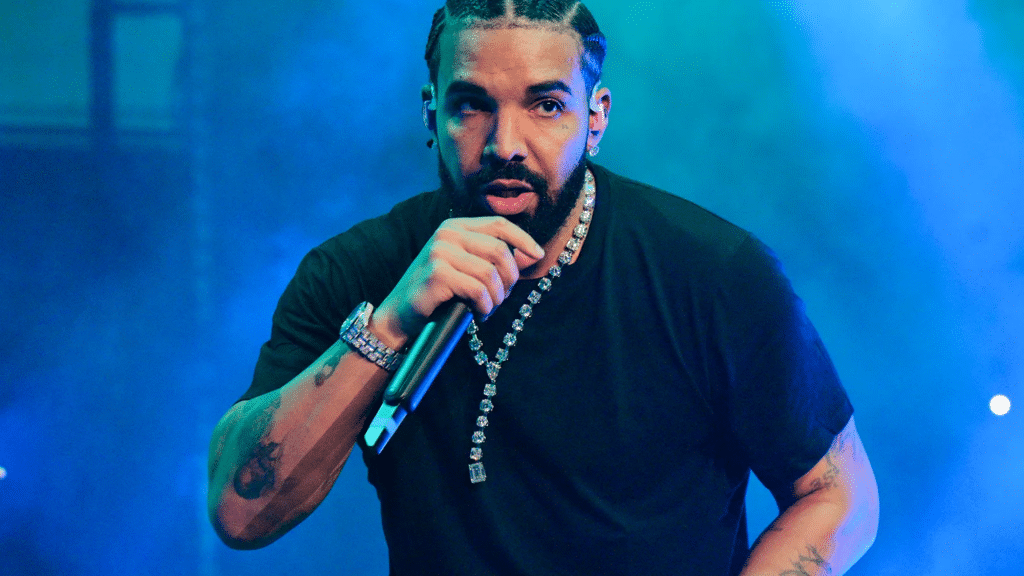

Are you curious about how many albums Drake has released so far? We have got you covered! From his start on Degrassi to becoming one of the biggest names in music, Drake has dropped hit after hit. But with studio

LATEST

Top Stories

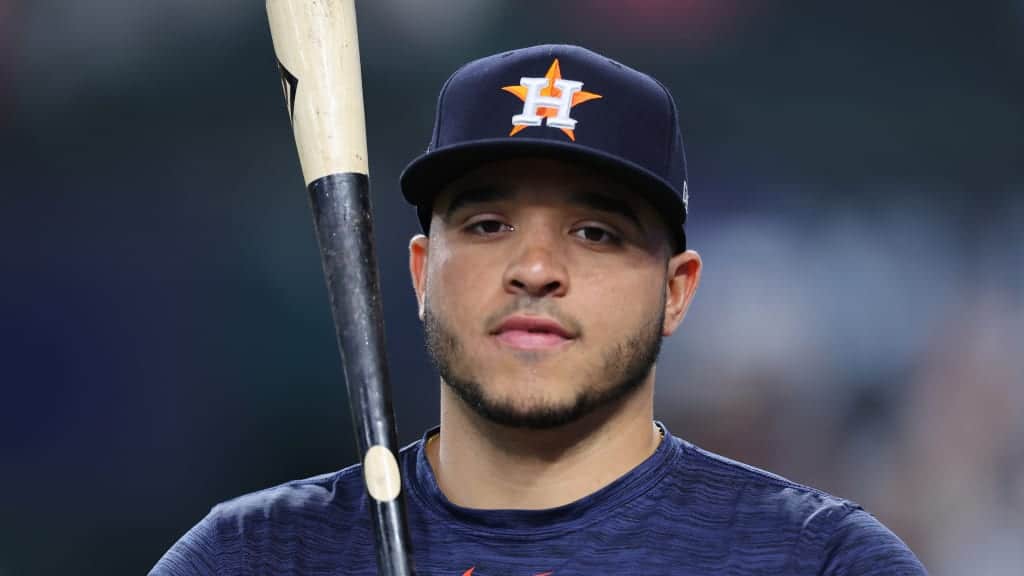

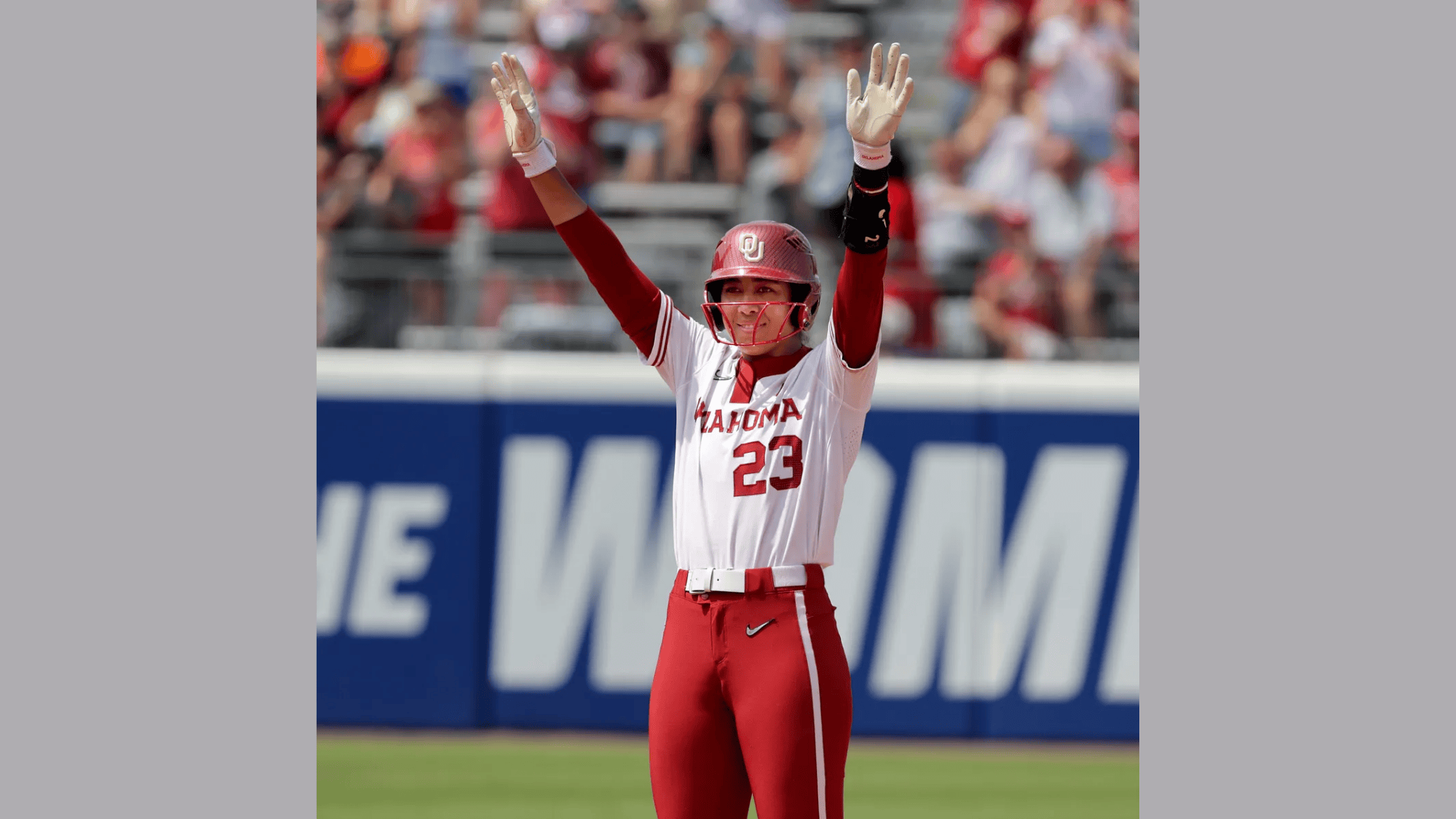

Yainer Diaz’s 2025 campaign represented both promise and challenge for the Houston Astros’ young catcher. The 26-year-old Dominican backstop finished the season batting .256 with 20 home runs, 70 RBIs, and 56 runs scored across 143 games. While these numbers

LATEST

Top Stories

Every semester, the same question circulates through dorm rooms and group chats: is getting help on an essay the same as cheating? The anxiety behind this question is real. Students want good grades, but they also want to earn them

Welcome to cuindependent, your space for bold ideas, fresh perspectives, and engaging stories. We bring you content that informs, inspires, and sparks conversation.

Stay connected — subscribe to our newsletter and never miss an update!

Explore

Our Picks

From inspiring artistry to achievements in sports and beyond, we bring the highlights.

A curated view of stories shaping conversations across fields today.

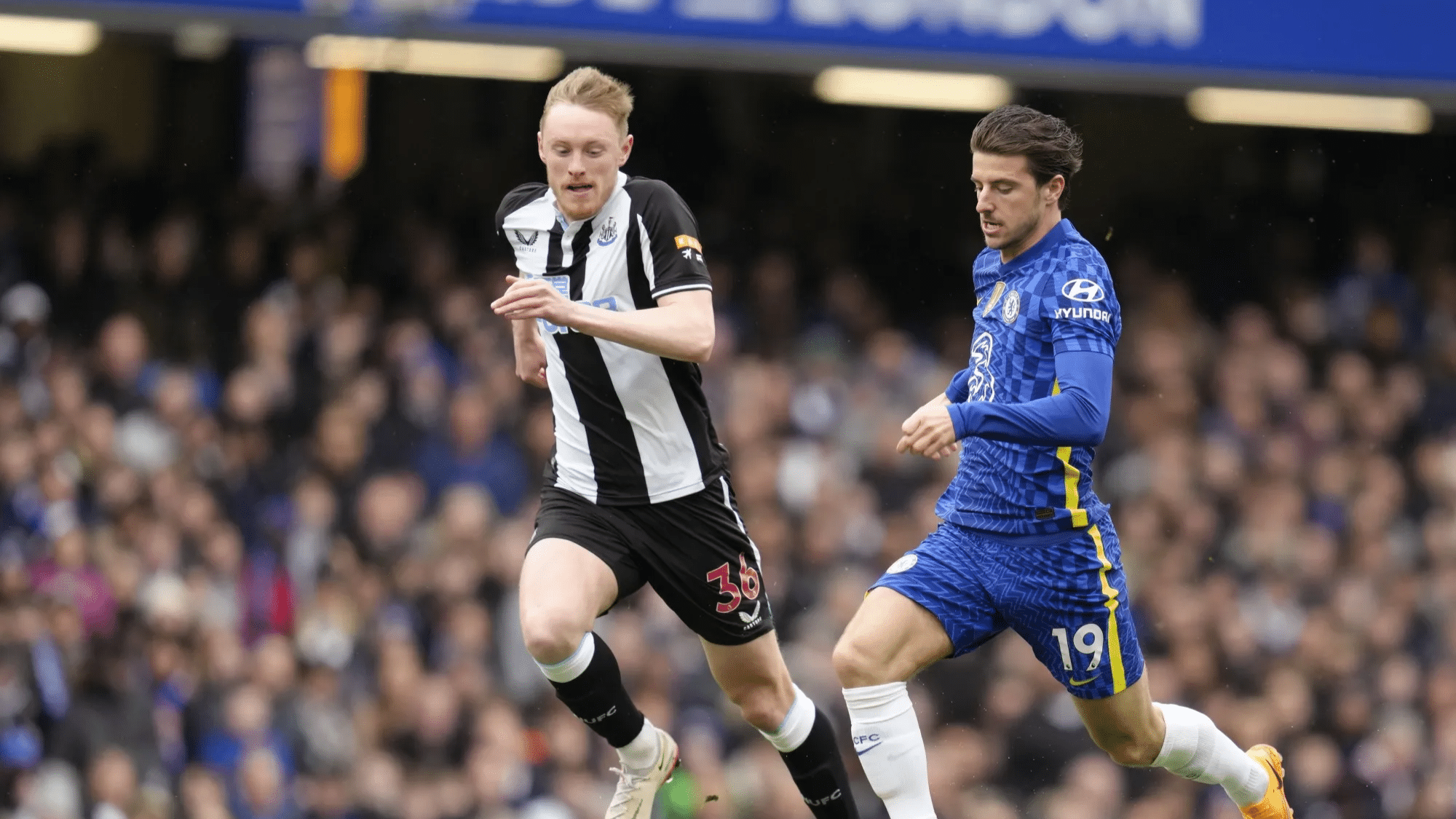

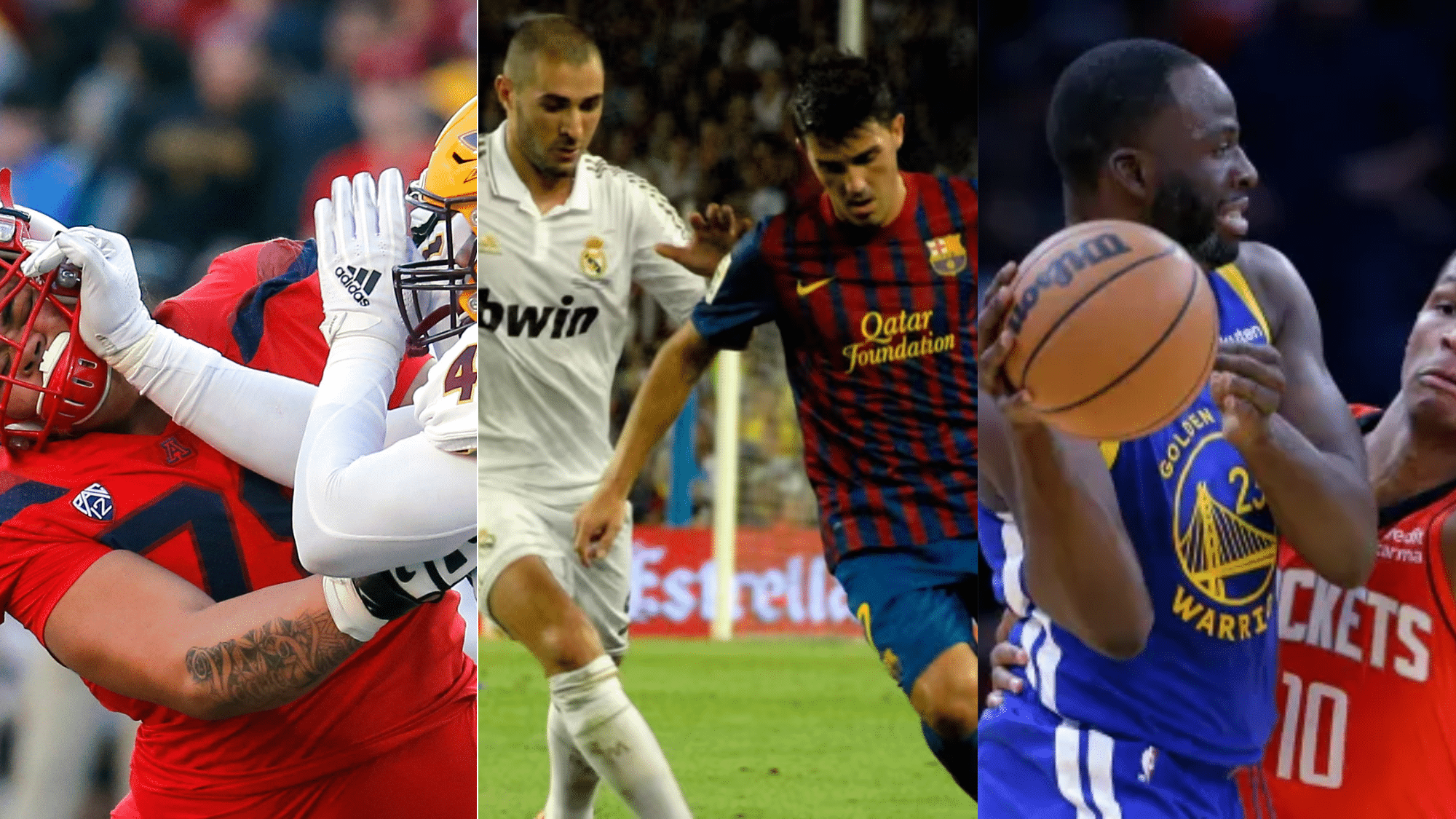

Some games aren’t just played, they are felt in the soul. These iconic rivalries go beyond the scoreboard, turning into battles of pride, passion, and identity that echo across generations. Whether it’s football in Argentina or cricket in India, these matchups light up stadiums, stir entire nations, and write unforgettable chapters.....

Fall is a magical season filled with vibrant colors, changing leaves, and endless creative inspiration. For teachers and parents, it’s the perfect time to introduce fall art projects that help children explore textures, colors, and nature while developing fine motor and creative skills. If you’re planning a classroom craft or.....

more

Meet Our Team

At CU Independent, we’re committed to delivering real, bold, and honest stories. Get to know the passionate team behind the content!

Samantha Lee

(Editor-in-Chief)

Dr. Alex Thompson

(Senior Features Writer)

Meet Our Team

Hootie & the Blowfish is a beloved American rock band, best known for their chart-topping hits in the 1990s. Formed in 1986 in Charleston, South Carolina, the band quickly rose to fame with their unique blend of pop, rock, and blues. Their catchy songs and relatable lyrics connected with fans, making.....

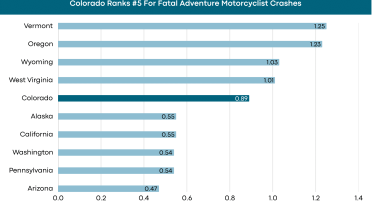

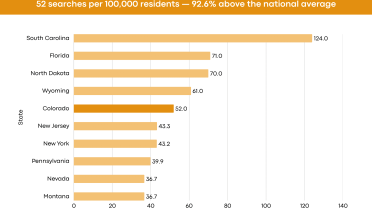

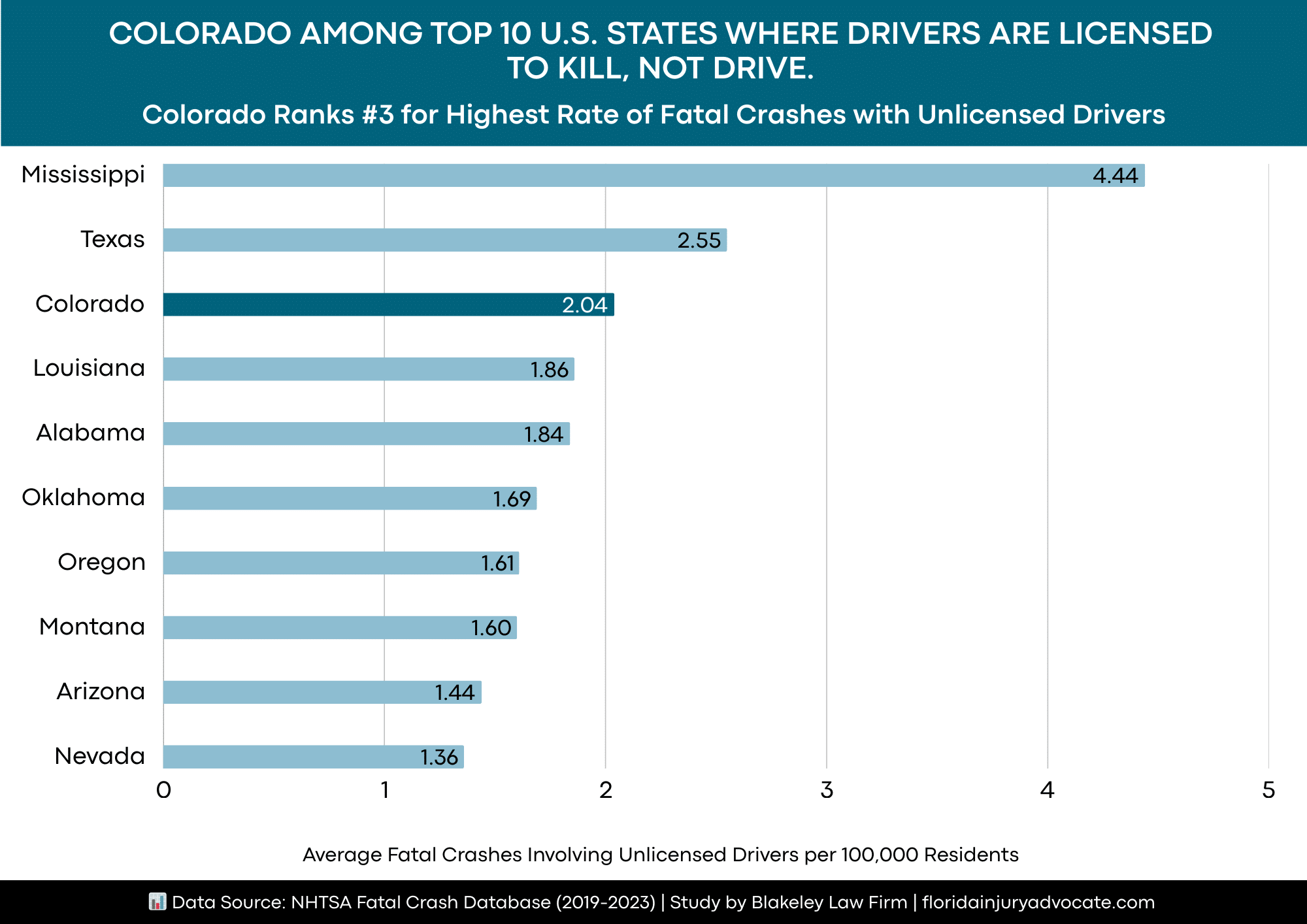

A new study reveals that Colorado has the third-highest rate of fatal crashes involving unlicensed drivers in the United States. The study by Florida-based Personal Injury lawyer Blakeley Law Firm analyzed fatal crash data involving unlicensed drivers from 2019 to 2023 across the U.S. states, via the NHTSA database. Using population.....

The Australian countryside isn’t just known for its stunning scenery, but its harsh conditions as well. Living and working in the rural areas requires a tough spirit and equally tough clothes. If you are looking for clothing that can take you from cattle stations to rodeos and everything in between, then.....

As future DOs, are you feeling the weight of the COMLEX Level 2 prep already? It’s totally normal! That massive exam can feel like trying to drink from a firehose, but honestly, a strategic study plan makes all the difference. We’re going to talk about building a balanced system—one that uses.....

Our Contributors

As Seen On