Graphic by Ben Berman

The women’s rights movement flourished in the 70s. In 1972, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment, which legally prohibited gender discrimination. In 1973, the Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade legalized abortion. Beyond the political scene, women asserted themselves in mainstream arts and culture, especially in male-dominated musical genres like rock ‘n’ roll.

For Women’s History Month in 2021, the CU Independent arts staff pays tribute to a few of these influential female musicians of the 70s and their enduring legacies. The full playlist, “Women of the 70s,” can be found here.

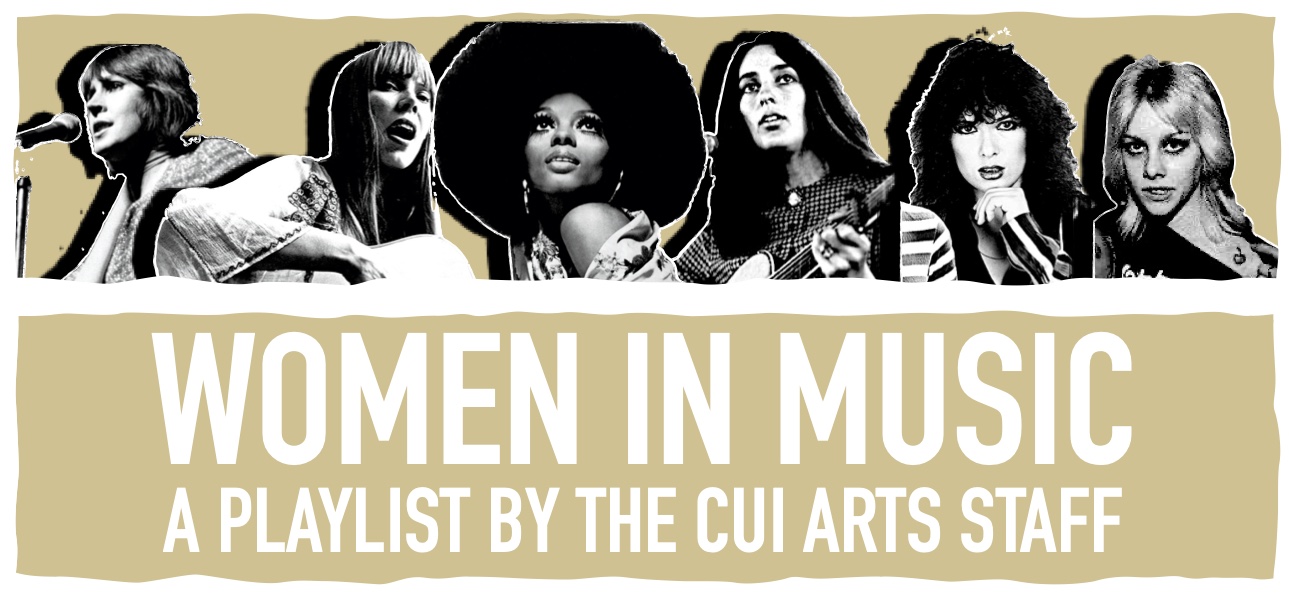

“Surrender” — Diana Ross (1971)

Diana Ross’ “Surrender” (Courtesy of Motown Records)

Diana Ross, the Queen of Motown, dominated the 70s. She released 10 chart-topping albums, starred in the Academy Award-nominated film “Lady Sings the Blues” and won a Tony Award. Her 1971 album, “Surrender,” was her finest release from that decade, closely followed by “Diana & Marvin” with Marvin Gaye, her self-titled 1970 debut and “The Boss.”

Unlike Ross’ usual pop-soul, “Surrender” is pure R&B, filled with sassy, confident vocals and funky grooves. The title track opens with a driving percussive beat and funky piano playing, as Ross belts out her self-assured demand, “Surrender your love baby // Give it to me.” Another major highlight is “I Can’t Give Back the Love I Feel for You,” debuted by Rita Wright in 1968. Ross reimagines Wright’s lackluster recording, infusing the song with drama and passion. Ross’ silky spoken confessions build into a lush, over-the-top climax, reminiscent of her breakthrough hit “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.”

In the bittersweet track “Remember Me,” Ross soulfully commands, “Remember me as a good thing,” backed by a solid gospel chorus and booming brass. The second half of “Surrender” settles down to a laid-back, jazzy vibe in “A Simple Thing Like Cry” and “Did You Read the Morning Paper?” until the fabulously funky “I’m a Winner” with snappy guitar riffs.

On “Surrender,” Ross creates an unmatched R&B masterpiece with emotive, passionate deliveries and poises herself for an unstoppable rise to R&B royalty through the 70s and 80s.

— Izzy Fincher, arts editor

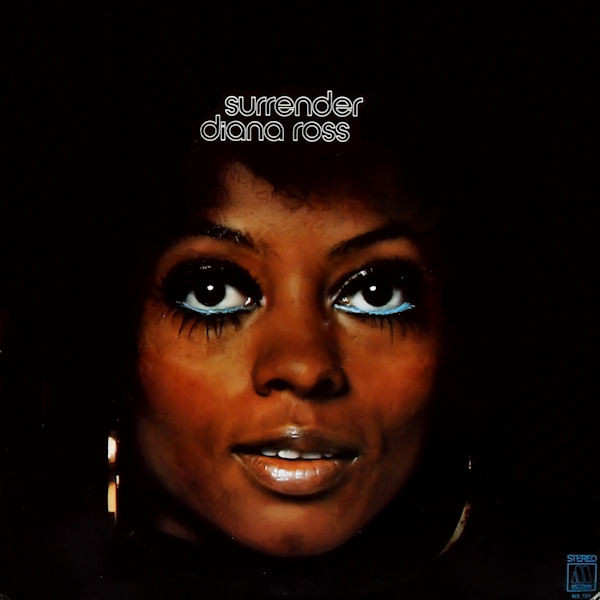

“The Runaways” — The Runaways (1976)

The Runaways’ self-titled debut album (Courtesy of Mercury Records)

The success of The Runaways, an all-teenage hard rock quintet, came and went before any of the band’s members could even legally drink. However, their short stint and debut album left a formidable legacy.

The Los Angeles-based group was put together in 1975 by producer Kim Fowley. Spearheaded by frontwomen Cherie Curie and Joan Jett, The Runaways curated an image oozing with hooliganism and raw youthful energy.

Their debut self-titled album is a boisterous glam-punk project with memorable tracks throughout. “Cherry Bomb” is a highlight with its catchy melody and anarchistic lyrics. “Can’t stay at home, can’t stay at school,” Curie snarls, setting the stage for the “Rebel Without A Cause”-like attitude of the band. Most of the album features straight-to-the-punch guitar riffs and cohesive instrumentation; however, the final track, “Dead End Justice,” is almost like a mini rock opera. It opens with hazy guitar loops and marching band-esque drum, leading into a whole conversation between Curie and Jett, ready for a night on the town. “Where am I? You’re in a cheap, rundown, teenage jail, that’s where!” they shout, wearing their rowdy hearts on their sleeves harder than ever.

“The Runaways” brandishes and remixes influences from many rock forbears. Yet, it also sets the stage for the glam-punk and metal that would follow into the 1980s, a movement led by Pat Benatar and later Joan Jett, following the group’s breakup in the late 70s.

More importantly, The Runaways subverted what it meant to be an all-female band, only six years after the serene attitude of the Summer of Love, as they brandished tattoos, flaunted trips to jail and provided a soundtrack to the ultimate bar fight. The Runaways cemented a place in music history as one of the first, and to date, most memorable all-female bands, proving to the male-dominated genre that five girls from Southern California could rock just as hard as the rest.

— Ben Berman, arts editor

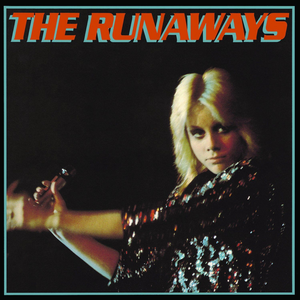

“Diamonds and Rust” — Joan Baez (1975)

Joan Baez’s “Diamonds and Rust” (Courtesy of A&M Records)

Over the course of her 60-year career, Joan Baez has released over 30 albums, but one stands out from the rest. Her 1975 release “Diamonds and Rust” remains the best-selling album of her career with good cause. Even diehard Baez fans are likely to agree that the title track may be her best work.

Baez rose to fame 15 years earlier performing traditional folk ballads, blues and laments. With an acoustic guitar, a handful of centuries-old songs and a terrible case of stage fright, the teen was an unlikely sensation. Her voice, at once sweet and powerful, captivated listeners. Her chill-inducing soprano and mesmerizing fingerpicking brought life and emotion to dusty, nearly-forgotten tunes and set her on a path to stardom.

In the years that followed, Baez often performed alongside her sweetheart, the then not-yet-discovered, Bob Dylan. She’d drag “Bobby” on stage, insisting that the crowd listen to his gritty, whiny voice and his lyrical mastery. She encouraged activism in him and watched him gain notoriety. During his 1965 UK tour, Dylan publicly broke her heart.

A decade later, he called her out of the blue and thus was born “Diamonds and Rust.” The title track recounts memories of lost love, spurred by that spontaneous phone call.

The album includes covers of songs originally written or performed by Dylan, Stevie Wonder, The Allman Brothers and John Prine, among others. The penultimate track “Dida” features a duet with another folk goddess of the era, Joni Mitchell.

Much of the artistry of “Diamonds and Rust,” however, comes from the intimate, poetic details surrounding the relationship between Baez and Dylan which appear in the title track as well as “Winds of the Old Days.” According to the title track’s lyrics, Dylan called Baez’s poetry “lousy.” If nothing else, she proved him terribly wrong with this masterpiece of an album.

Baez wears her heart on the vinyl sleeve of “Diamonds and Rust.”

— Georgia Knoles, managing editor

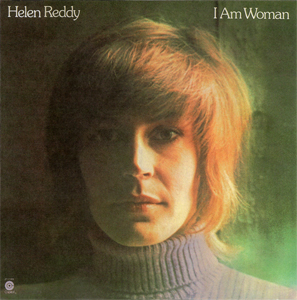

“I Am Woman” — Helen Reddy (1971)

Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman” (Courtesy of Capitol Records)

Helen Reddy had a difficult rise to pop stardom. The Australian-born artist only had $200 to her name upon her arrival to the US in 1966, but she refused to let this — or her inability to obtain a work permit — hold her back from musical success.

After years of singing in local lounges, struggling to pay rent and marketing herself to any record label that would listen, Reddy finally made her breakthrough. The B-side of her first single, a rendition of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” peaked at number 13 in the charts in 1971 and set Reddy on her way to becoming a star.

Her most popular single to date, “I Am Woman,” was released the following year. The track is an inspiring and empowering ballad describing the fight for women’s rights, and it quickly became an integral piece of the women’s movement in the U.S. Reddy won a Grammy for the Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for it and became the first Australian singer to top the U.S. charts.

The track features a classic 70s pop instrumental, accompanied by a brilliant vocal performance from Reddy. “I am woman, hear me roar// In numbers too big to ignore,” the artist sings, challenging her listeners to respect who she is and what she stands for. “I am strong (strong)//I am invincible (invincible)//I am woman,” she continues in the chorus, asserting her strength and power. The track is wonderfully empowering and reflects the feelings of countless women during their struggle for equal rights in the U.S.

In a 2003 interview with Australia’s Sunday Magazine, Reddy described the inspiration behind her smash hit. “I couldn’t find any songs that said what I thought being a woman was about,” she said. “I certainly never thought of myself as a songwriter, but it came down to having to do it.”

Even today, Reddy’s legacy lives on. The song was used as a tribute to Reddy after her passing in 2020 and continues to be a symbol for women’s rights and equality around the world.

— Marion Walmer, arts writer

“Dreamboat Annie” — Heart (1975)

Heart’s “Dreamboat Annie” (Courtesy of Mushroom Records)

Heart became a household name in the hard rock scene of the 70s with their catchy blend of folk and psychedelic aesthetics. Although the band’s success would not carry over to the next decade, their folk/hard rock sound captivated many rock fans, amidst the rise of punk and progressive rock. Heart’s breakthrough happened with their debut album “Dreamboat Annie,” a commercial success, which led to the band signing with a major label and eventually becoming a household name.

The opener “Magic Man” is a great example of the band’s ability to balance technical prowess and catchy pop tunes. The melodic guitar solo and the psychedelic keyboard section don’t overstay their welcome, as many prog-rock tracks from the era did, while the passionate vocals and the catchy chorus take the lead. Another highlight is the title track, a dreamy acoustic folk song, that appears in three different variations in the album. This is a risky artistic choice, but one that pays off. The biggest commercial success from the album is “Crazy on You,” a track that seamlessly combines hard rock and folk.

Despite a few unmemorable tracks later on, the star-studded opening tracks carry the record and display the potential of the band to be a chart-topping success.

— Altug Karakurt, arts writer

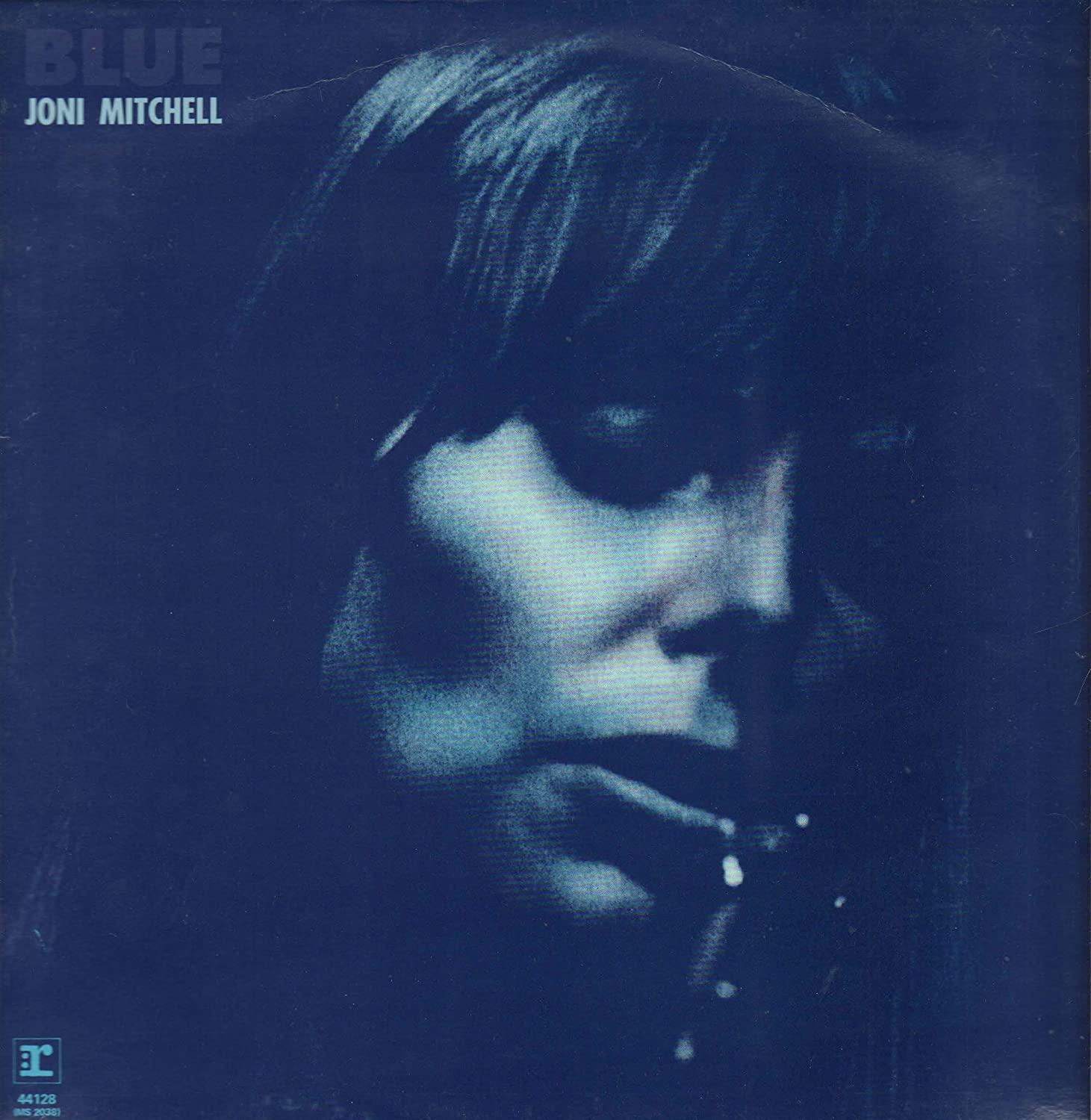

“Blue” — Joni Mitchell (1971)

Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” (Courtesy of Reprise Records)

Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” transformed folk music forever. Even 50 years later, it remains a genre-redefining masterpiece with unparalleled poeticism and authenticity.

On “Blue,” her fourth studio album, Mitchell dives headfirst into sadness and heartache. The title is simple yet evocative, a nod to “feeling blue.” At the time, Mitchell found herself at painful personal crossroads, a few years after putting up her newborn daughter for adoption. In a 1979 interview, Mitchell admitted, “I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes. I felt I had no secrets from the world, and I couldn’t pretend in my life to be strong. Or happy.”

In the title track, Mitchell dedicates a song to sadness. She compares it to a vast blue ocean — she can choose to drown in it with “acid, booze and ass // needles, guns and grass” or “sail away.” In “River,” a depressing Christmas song, Mitchell reminisces about childhood holiday traditions before confessing, “I wish I had a river I could skate away on.” In “Case of You,” she is intoxicated by an unhealthy, addictive love, which she compares to “holy wine,” claiming “Oh, I could drink a case of you, darling // And I would still be on my feet.”

On “Blue,” Mitchell’s vulnerability is astounding. Yet, despite the intimacy and personal details, overall Mitchell leaves enough ambiguity to capture sadness in a heartbreakingly relatable way.

— Izzy Fincher, arts editor