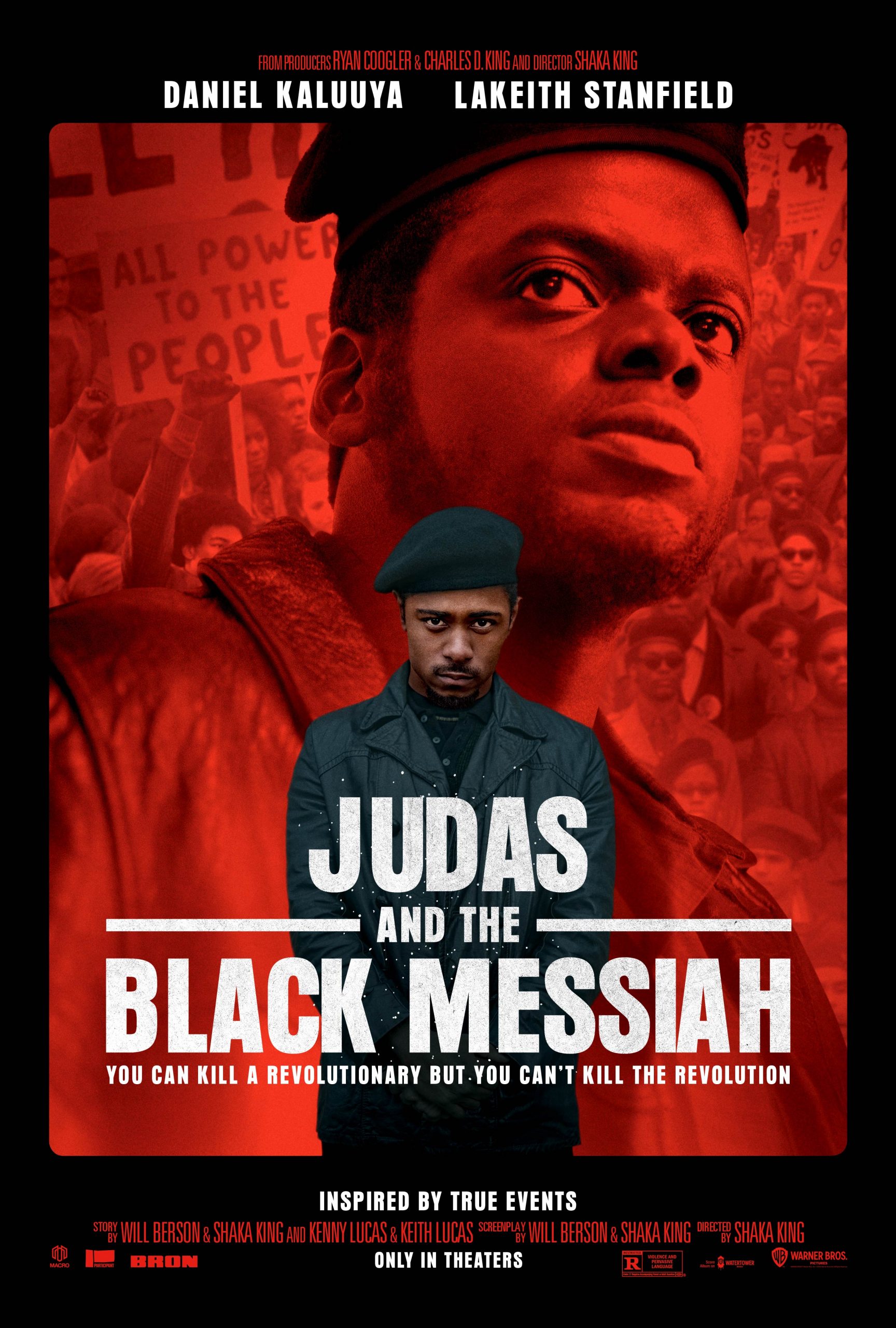

“Judas and the Black Messiah” (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

In a film that draws upon the Biblical story of Judas, the villainous figure that betrayed the righteous Jesus, one might think the lines between good and evil are clearly laid out. Subverting that trend, Shaka King’s new film “Judas and the Black Messiah” boldly thrusts the role of Judas upon that of the amoral middleman — using the unique perspective to explore the merits and pitfalls of taking a neutral, betraying stance in times of upheaval.

Based on a true story, “Judas and the Black Messiah” centers on the last year in the life of the “messiah,” Fred Hampton (played by Daniel Kaluuya of “Get Out” and “Black Panther” fame), a young activist and chairman of the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter. At only 21 years old, he had a meteoric rise through the ranks of the at times extremist organization, only to reach an untimely demise when killed by Chicago Police in 1969 in a targeted raid. The film centers on his final months, where he was a significant target of the FBI, who in the late 1960s sought to “prevent the rise of a messiah who could unify the militant black nationalist movement,” a fear espoused in the film by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen).

The acting strengths of the main cast define the film’s narrative, injecting the well-written script with a wide range of emotions. Despite its brutally honest retelling of historical events, King’s direction shies away from heavy exposition and lets the audience discover the context of 1968 Chicago through the film’s potent character moments, a unique feat not often found in biopics.

Kaluuya’s electrifying performance, full of fist-raising, impassioned sermons, is an obvious highlight of the film — a clear casting choice that does justice to the real-life Hampton, whose footage briefly appears in the film. His role as the savior of the Black population against white America draws easy comparisons to Jesus as the messiah of the Jews against the Romans. But instead of focusing solely on Hampton, which would have been the standard route for a feel-good, hero-wins-the-day biopic about the Black movement (think back to 2018’s “BlacKkKlansman”), the film takes a darker approach by lending more interest to the villain than the hero.

William O’Neal (played by LaKeith Stanfield of “Straight Outta Compton” and “Atlanta”) is the Judas to Hampton’s messiah, a Black man and car thief incarcerated for impersonating federal officers. Rather than face jail time, he strikes up a deal with the FBI: infiltrate the Black Panthers and rat out Hampton. With his freedom on the line, O’Neal takes the deal without hesitation.

The film centers around the fallout from O’Neal’s decision, where we follow the double agent’s tormented conscience as he does the work he was enlisted to do, for no other reason than to save his own skin. With O’Neal acting as an audience surrogate, we get an outsider’s perspective of the boisterous Black Panther movement as it unfolded, its triumphs and unity quickly feeling forgotten the moment the film seamlessly pivots from the warm glow of its rallies to the cold, sterile security chambers where O’Neal meets with his liaison, FBI Officer Roy Mitchell.

Played by character actor Jesse Plemons (“Breaking Bad,” “Fargo”), Mitchell gives off a chillingly sinister energy that never reaches the highs of the lead performances but establishes a telling dynamic with O’Neal, who he chats with at numerous points in the film, each time reeling the torn O’Neal back into the mission and sealing his fate further.

One of the film’s strongest moments comes through the scene of O’Neal’s initial incarceration, where he’s seated in front of Mitchell, who repeatedly asks him how he felt about the then-recent murders of Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Mitchell circles him like a hungry shark and smirks subtly when he realizes O’Neal is indifferent to the Black liberation cause. This scene becomes all the more memorable by the end of the film, when the viewer sees the full transformation from O’Neal’s directionless, amoral beginnings to his legacy in history as a complicated, conscience-tortured villain.

While the performances of Kaluuya and Stanfield give appropriate weight and emotion to the film’s tragic climax, the historical context of the narrative, compounded by the perspective of the FBI and O’Neal, gives the film a fitting and refreshing sense of nuance. While there are a clear hero and a clear villain—Hampton’s role as a tragic martyr and the FBI’s obsessive destruction of his life’s work—”Judas and the Black Messiah” takes larger advantage of the perspective of the neutral party. By focusing on O’Neal’s tragic involvement based on forced coercion and his undertaking of a role in history he never sought out himself, the disturbing Biblical tale of Judas is retold in this film. Teaching us betrayal and corruption will always prevail in society, “Black Messiah” delivers the potent message through both a humanizing and a villainous lens that mirrors the tumult and confusion of the 60s — always timely lessons that persist today.

Contact CU Independent Arts Editor Ben Berman at ben.berman@colorado.edu.