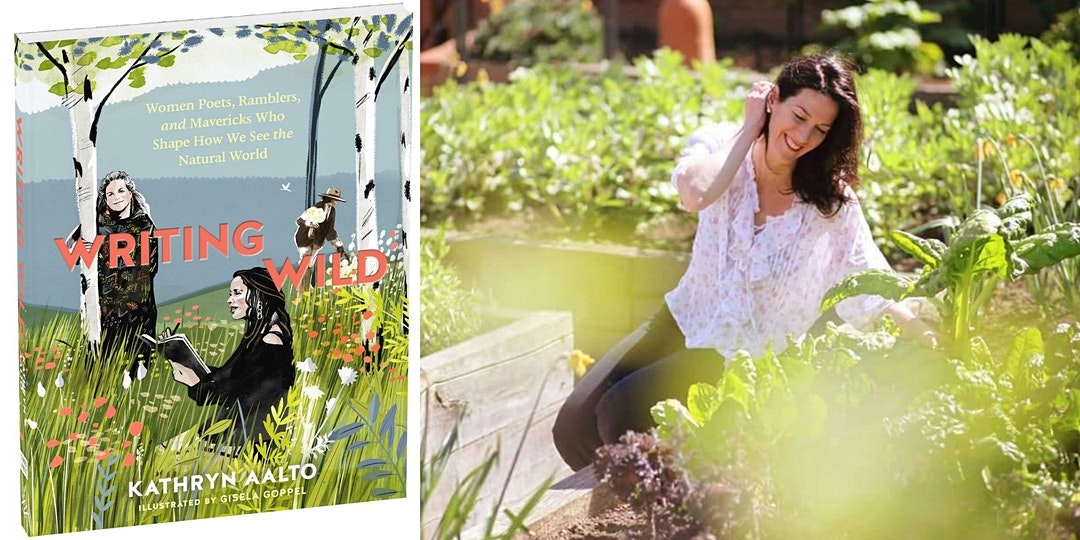

Kathryn Aalto and her new book, “Writing Wild.” (Courtesy of Kathryn Aalto)

�I feel like going slowly is the way to best experience a place, even better than riding a bike, and certainly better than a car,” says historian, naturalist and writer Kathryn Aalto. “I just feel like you get a sense of place better through that.�

Taking it slowly is exactly the mantra behind Aalto’s latest project, “Writing Wild.” In the book, published June 23, she uses a unique blend of historical analysis and personal essay to explore and celebrate the work of 25 female nature writers, a focus she calls “eco-feminism.”

Though she now resides in Exeter, England, Aalto traces her roots to Escalon, a tiny farming community in California’s San Joaquin Valley. There, she found a passion for creative non-fiction both as a reader and writer. In her early twenties, she was drawn to the essays of 19th century naturalist John Muir.

“He was describing (California�s) Central Valley. He wrote about walking from San Francisco to Yosemite National Park,” she said, “I became interested in several parts of it.�What was the Central Valley before it became the breadbasket of the world?�

This led Aalto to venture into the travel essay genre, where she explores “people’s relationship with the natural world and the natural history of places.�

However, after developing a fascination for the past, Aalto saw a major issue with it. She began to feel that “nature writing was all writing by dead, white guys.”

To remedy this, Aalto looked back to her time as an English student at UC Berkeley, where she read the works of female writers, spanning from 19th century Romantic Dorothy Wordsworth to modern-day activist Caroline Finney.

�I wanted to bring as much diversity in as possible and let people know how multifaceted nature writing by women was,” she said.

Through this, Aalto began work on her book “Writing Wild,” not only celebrating the achievement of over two centuries of female writers but also shedding a harsh light on the struggles they faced on their journeys.

“(Dorothy Wordsworth) wandered at a time when women were not allowed to walk alone. They would be called sexually promiscuous. We couldn’t go to university, or write under our own names.”

Along the way, Aalto traverses across different locales, from the smallest ponds to the tallest mountains in the English uplands to put the readers in the shoes of both Aalto and all the women that inspired her.

Aalto traveled to Scafell Pike, England’s tallest mountain, during the research process. Scafell Pike is the setting of the opening essay in “Writing Wild.” (Courtesy of Kathryn Aalto)

While “Writing Wild” honors the past plenty, Aalto made the future a major aspect of the project as well, using later chapters of the book to focus on issues that happen to be especially pertinent in 2020.

One essay focuses on the writings of Elizabeth Rush, an author known for her works on climate change as recently as 2018’s “Rising.” Aalto was inspired by how Rush “weaves prose with scientific writing” to send a strong message about how we treat nature in the 21st century, something Aalto wanted to emphasize in “Writing Wild.”

Though the book was published in June, Aalto also sees comparisons that can be made to 2020’s summer of racial reckoning, further fanned by a tumultuous political climate.

�If you’re black and you look at a tree in a park where there is a history of lynchings, you’re gonna look at that tree, and perhaps even wilderness, differently,” she explains, looking to honor the voices of black environmentalists,�”Whereas white people, privileged by the color of our skin, would not have that in our family history. So I wanted people to have a new appreciation outside the Eurocentric perspective.�

Despite weaving a complex history with ugly truths at times, Aalto remains confident that stepping back to appreciate nature can “show�people how far we’ve come in the simplest of ways we take for granted.�

In times like these, maybe going for a slow walk through the woods can bring us the perspective we all need.

Aalto’s new book, “Writing Wild,” can be found here.�Additionally, the Boulder Book Store will be hosting Aalto on Thursday,�Sept. 10 for a virtual discussion about her work. More information about this event can be found here.

Contact CU Independent Assistant Arts Editor Ben Berman at ben.berman@colorado.edu.