The final edition of the Rocky Mountain News. Courtesy of Denver Public Library.

John Temple still remembers Feb. 27, 2009: the last day of publishing for the Rocky Mountain News, Colorado’s flagship newspaper. Temple, the last editor, publisher and president of the publication, saw its end coming for some time. It was a devastating finish to an outlet that Temple characterized as “uniquely Colorado.” It was also one of the first major newspapers in the country to fold, beginning a string of closures during what Temple called a “really terrible time” for the traditional journalism model.

“The community lost a partner, a force, an important voice,” Temple said in an interview a few weeks before the anniversary. “We were people-oriented. We were very focused on certain issues that really mattered to people. The Rocky was a special experience.”

In the 10 years since the Rocky’s closing, Colorado’s news landscape has changed rapidly, both for journalists and for readers. The primary news outlet for the Front Range and greater Rocky Mountain region is now The Denver Post, once the Rocky’s competitor, yet struggling nowadays. Add in the 2016 presidential election and the concept of “fake news,” the rise of digital media consumption, and aggregation platforms like Facebook and Google, and it’s hard to say if one specific reason led to the uncertain state of journalism today.

“People maybe understand a little more about what’s going on in the news industry in Colorado because of how public the issues at The Denver Post have been,” said Corey Hutchins, a writer for The Colorado Independent and a contributor to the Columbia Journalism Review. The Post’s cutting of about a third of their reporters in early 2018, coupled with a scathing editorial by then-editorial page editor Chuck Plunkett on The Post’s parent company, MNG Enterprises (also known as Media NewsGroup or Digital First Media), have put the region at the front and center of the conversation.

In the years since the Rocky’s last issue, publications have come and gone without a definitive formula of what works. One initiative, the Colorado Media Project (CMP), is trying to figure that formula out. The organization is funded by the likes of the Gates Family Foundation, Project Excite and Democracy Fund. (Temple is on the group’s local advisory committee.) It released a report in September 2018 with results from a survey on how Coloradans consume journalism. With over 2,000 respondents from across the state, the survey showed that while many readers consume national news first, their second priority is local news. Many of the respondents said they would support local news, yet weren’t aware of newer brands in the region.

On Feb. 19, CMP announced a new phase of their work, with $300 million of support added from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. That funding, stretched over five years, contributes to the group’s next phase of work ? building up support and involvement with local journalism in Colorado. Nancy Watzman, CMP’s acting director, says that a sustainable news environment requires emerging outlets to do outreach work, as well as citizens who have the means to do so stepping up to support it.

“I’m hoping for homegrown, vibrant, strong organizations delivering much-needed news to citizens so they can make good decisions,” Watzman said. “These things are fragile. Connections need to be made at the ecosystem level.”

Too much to cover, not enough time

Though there’s a definite decline in reportage, it’s not for lack of trying. The CMP’s Benchmark Report highlighted multiple outlets, including newer ones like Denverite and Aspen Journalism and more established outlets like Chalkbeat Colorado and The Colorado Independent, that are trying different tactics. Even for those that are growing their operations ? such as Colorado Public Radio, which recently announced an initiative to add nine reporting positions to its newsroom in the next few years ? it’s clear that both journalists and audiences are favoring specialization. In CMP’s analysis, one third of the organizations analyzed were focused on a single topic.

For some outlets, that means covering one topic, such as Chalkbeat’s focus on education or High Country News’ emphasis on the environment. For others, it means geographic specificity, like Denverite or the Longmont Observer.

Even Westword, the Denver-based alt-weekly that’s been around since 1977, is choosy about their coverage. Though they don’t strictly limit themselves to the metro area, a majority of their stories focus there. Patricia Calhoun, the editor-in-chief and one of the founders of the news magazine, says that if she knows another outlet or journalist is covering a story, she’ll redirect the staff’s attention elsewhere. They used to publish two longform articles a week; nowadays, it’s usually only one.

“We’ve lost a lot, and I’m worried every single day that bad people are doing bad things and getting away with it,” Calhoun said. “On the flip side, there are people doing good things that don’t get covered either.”

One outlet is even trying to specialize in reporting style. Launched in September 2018, The Colorado Sun is an online news outlet based in Denver that covers issues around the state. Dana Coffield, senior editor and one of the founders of The Sun, says the news site prioritizes in-depth coverage over day-to-day briefs, which The Post and other outlets often don’t have the resources to do. The Sun’s free email newsletter, which runs three times a week, has close to 18,000 subscribers, with about two-thirds of the emails opened every time. Considering the average open rate for a newsletter is about twenty percent, Coffield says it indicates people are catching on.

“Either we’re proving something works, or we went down trying,” Coffield said.

Many of the staffers at The Sun come from careers at The Post or the Rocky Mountain News. Coffield worked at the Rocky from 1997 to 2000, and started working at The Post in 2003, which is where she was six years later when the Rocky closed its doors. She remained at The Post until her voluntary departure in the summer of 2018 after hitting a point where efficacy “felt insurmountable.”

“It didn’t matter how hard I worked and innovated, it wasn’t going to change anything,” Coffield said.

To be fair, Coffield says she has no hard feelings against The Post. She, as well as other journalists interviewed for this article, cite a lack of resources, in part due to the rapidly shrinking newsroom, as the main issue, not the writers and editors themselves.

“I love that newspaper, that legacy, those people,” Coffield said. “You feel bad leaving, but if the opportunity presents itself and you have a good idea, you should go.”

She misses the Rocky, especially the competition between it and The Post. Competition in a news environment has been shown to encourage better journalism, with reporters racing to beat each other to the story and then working to write it better than their competitor. This historically led to the public getting ample information about a wide range of issues. Coffield says that it doesn’t feel like Colorado’s news environment has that luxury nowadays.

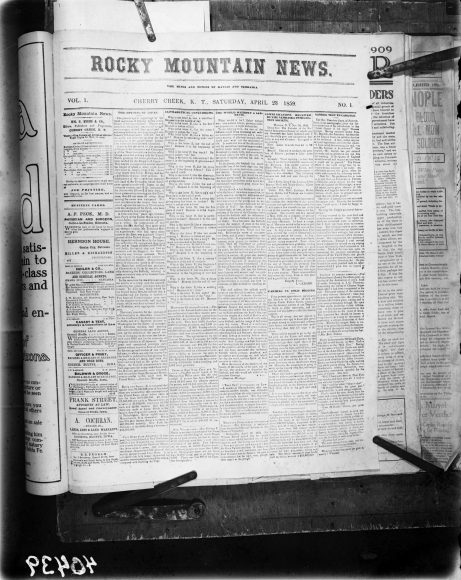

The first edition of the Rocky Mountain News. Courtesy of Denver Public Library.

Financial Viability

For rising outlets, part of the ambiguity is economic. The jury’s still out on exactly how often startups fail, but multiple studies suggest that at least a majority of new companies don’t make it.

Westword is one exception to the funding issue. Their content has been free since its first print issue in 1977, continuing with the addition of a website, thanks to advertisement sales. In the past few years, marijuana advertisements have constituted a large chunk of that, which Calhoun says is somewhat lucky, as they’re a natural fit for Westword’s publication style.

“Information wants to be free and free things do have value, which industry people didn’t believe at first,” Calhoun said.

For other outlets, the struggle to stay afloat in the long term is often uncertain. One example is the Longmont Observer, a nonprofit site based on community member contributions. Started in 2017, the new outlet looked to fill a need for hyperlocal coverage that the Longmont Times-Call, the original information source for the city, just wasn’t able to cover. The Times-Call is owned by MNG Enterprises, the same group that oversees the Denver Post and the Boulder Daily Camera.

The bulk of the Observer’s work comes from volunteers or freelancers, with just a handful of paid staff. Macie May, the editor-in-chief, says that just through word of mouth ? the most advertising they’ve done is a boosted Facebook post ? they’ve reached about a quarter of Longmont, indicating that the community likes what they’re seeing. Still, financial stability in the long term is unclear.

“While we would love to be able to replicate the Observer throughout Colorado, right now we’re trying to make it sustainable in Longmont first,” May said.

The model varies from outlet to outlet, with hybrid subscriptions or pay-as-you-can as a common theme. The Colorado Sun’s initial funding comes from Civil, a blockchain-based organization. Over the first two years of their work, the company intends to develop a sustainable income through memberships, partnerships and more, with the tiered membership model already debuted. On their second lowest tier and above, they offer a subscriber-only politics newsletter, The Unaffiliated. Higher tiers offer perks like access to an exclusive Facebook group for discussion, recognition on what they’re calling the “Booster wall,” early ticketing for community events, and more.

It’s a bit different for nonprofit organizations. The Colorado Independent relies on grants and donations. The Longmont Observer has memberships from both individuals and businesses.

It’s not clear if there’s one model or format that’s going to be most viable in the coming years. For Temple, “ten years ago is a long time,” and he thinks a lot of journalists have moved on, though for some, the Rocky was their last reporting job. However, he says he’s encouraged by both new and existing outlets trying new tactics.

“Colorado’s a complicated place,” Temple said. “It needs horsepower and resources to do a great job on politics, the environment, education, and more. It requires a committed effort. My hope, long term, is that journalism becomes better than what we were able to do at the Rocky.”

Correction: this story has been updated to fix inaccuracies regarding when Coffield was employed at the Rocky Mountain News. The article previously stated that Coffield was working there when it closed in 2009, when she actually worked at the Rocky from 1997-2000 and The Post from 2003-2018. We apologize for the error.

Contact CU Independent Staff Writer Lucy Haggard at lucy.haggard@colorado.edu